Homelessness: a national scandal

Since 2010 the scope and scale of homelessness has steadily increased. It is time to demand the government ends this tragedy, once and for all, writes Daniel Sleat.

Since 2010 the scope and scale of homelessness has steadily increased year on year. Analysis last November showed 320,000 people are now recorded as homeless. Many of these people are living in temporary accommodation like hostels or shelters.

At the very sharp end of homelessness is rough sleeping. Over the last nine years the number of rough sleepers on our streets has almost trebled from 1,768 to 4,677.

The causes of this crisis are complex, yet the solution appears clear.

But first, how have we reached this point?

House prices have risen dramatically since the 1980s and are now higher than most other countries. Incomes have not kept pace with these rises, particularly for young people.

In addition, post the 2007 financial crash, the rate of lending to first-time buyers – the vast majority of whom need a mortgage to get a foot on the property ladder – dropped sharply as banks retreated from riskier lending.

As a result of these factors, the number of people who own their own home has decreased and the size of the private rented sector has risen considerably – with the number of households renting privately more than doubling between 1997 and 2017 (going from 2.1 million households, to 4.7 million).

The move away from home ownership to private rented accommodation has been particularly pronounced among those on low incomes.

Housing benefit cuts and freezes since 2010 have led to the local housing allowance failing to keep pace with the cost of rent. In central London there is a weekly shortfall of £371 between the local housing allowance rate and the cheapest 30 per cent of private rented homes. Shelter estimates that if this policy is not changed in the next year, 83 per cent of areas in England will be unaffordable for those receiving local housing allowance.

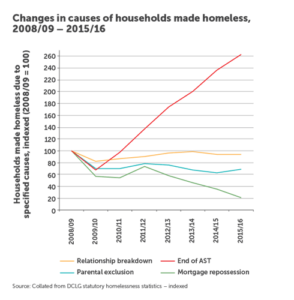

The overall outcome of these factors is that the end of a short-term private tenancy is now the leading cause of homelessness, as shown in the graph below

This situation is of course made worse by other linked causes, including the significant decline in social housing construction.

The tragedy of much of the current situation is that there are clear answers at hand.

First, short-term action is needed from government. Lessons must be drawn from the last Labour government’s success on rough sleeping, with targeted cross-government action underpinned with the proper financial support from the treasury.

Another feature of this immediate action must be a recognition that whatever the political rhetoric on homeownership, put bluntly we have moved to a European-style rental system but without the controls those countries have.

Section 21 “no fault” evictions are a big issue in this regard. The government’s move this week to consult on scrapping them is therefore welcome, but to be effective it must form part of a wider radical package of reform. This must include tackling the issue of unfair rent hikes, which Generation Rent rightly raised in response to the announcement of the consultation this week.

Further steps would involve legislating to increase the minimum tenancy from six months. The government consulted on a change to three years and Labour recently proposed supporting indefinite tenancies, based on the German system. Under such changes a landlord would retain the right to evict a tenant if they do not pay rent and tenants could still give notice to move out. But it would begin to rebalance the relationship between tenant and landlord and avoid unfair evictions, especially if combined with further reforms to strengthen the rights of tenants.

Urgent action is also needed to relink the local housing allowance with the 30th percentile of local rents.

These short and medium-term steps must then be coupled with the right long-term plan. On the basis of the evidence available, a move towards a Finnish-style ‘Housing First’ policy seems compelling. Unlike the prevailing trends in much of Europe, Finland has dramatically reduced homelessness through the introduction of the Housing First model, under which homeless people are given a permanent home straight away and the other underlying causes of their homelessness are given space to be properly resolved.

For Housing First to work, however, we first need more housing. Shelter’s social housing commission has called for a dramatic increase in social housing, arguing for at least 150,000 new social homes per year over the next two decades, at a net cost to government of £5.4bn per year.

The sad truth is that homelessness has become one of a range of pressing domestic policy issues that have been subsumed by the all-encompassing chaos of Brexit. It is not, and cannot ever be good enough, however, for people to be sleeping on our streets, or living in insecure housing, when action could be taken. It is time to demand the government ends this tragedy once and for all.