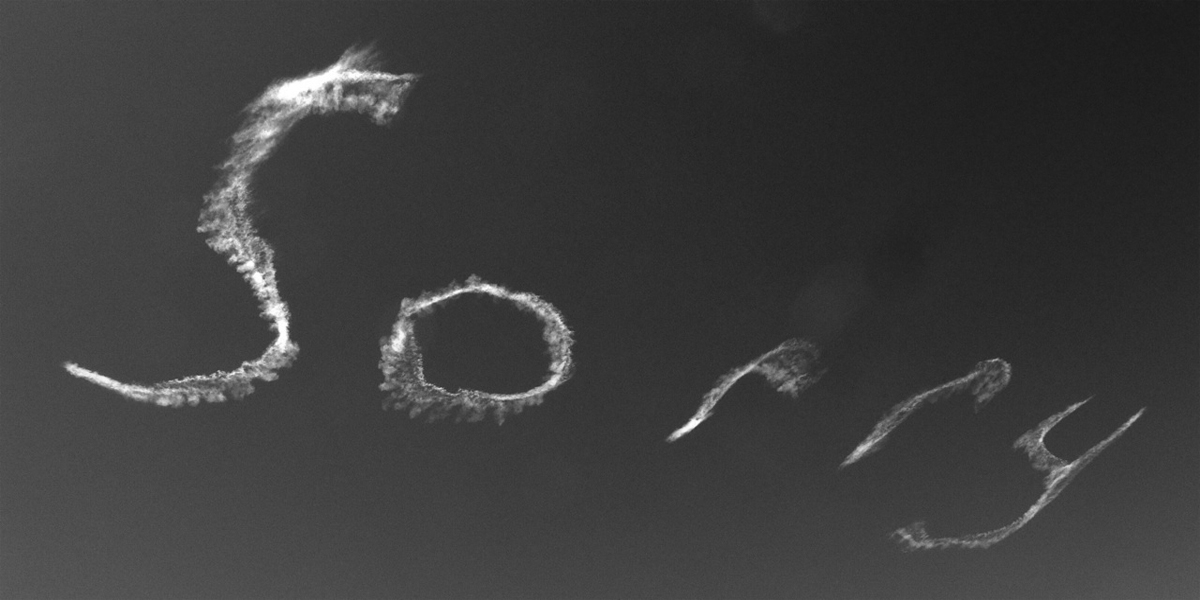

Beyond apology

Labour’s masochism strategy has us trapped picking over the bones of our past when we should be talking about the country’s future. In arguing that things the last Labour government actually got right we got wrong, we seem intent on...

Labour’s masochism strategy has us trapped picking over the bones of our past when we should be talking about the country’s future. In arguing that things the last Labour government actually got right we got wrong, we seem intent on doing our opponents’ job for them and, even worse, on offering mechanistic responses to what focus groups say rather than credible policy solutions to what the public mean.

Fabians are often parodied as believing Labour’s renewal needs just ‘one more heave’, that past failed strategies simply haven’t been pursued vigorously enough. Such criticism tends to come from those to whom it could be better applied, the people who think all we need to do to cover the left’s weak political flanks is administer just ‘one more kicking’ to benefits claimants, the European Union or Britain’s migrants and minorities. On this analysis, a synthesis of New Labour triangulation and Blue Labour turbo-communitarianism, the priority is mirroring focus group fury without meaningful investigation into its emotional drivers or serious consideration of its governing implications.

That can never be a strategy for victory, because it fails to understand that our national conversation is taking place in code: voters use a whole host of terms as shorthand for unmet emotional needs they expect leaders to satisfy and not simply repeat.

Thus the prime minister and his headline-happy advisers, afflicted by precisely the same crude reductionism which led Labour to respond to increased public alarm about terrorism with a bidding war on pre-charge detention, have been bewildered to discover how voters actually use words like ‘scrounger’. They don’t use them to guide politicians in making complex trade-offs about the distribution of Britain’s bedrooms but to express a whole host of connected feelings about desert and belonging and shared reward.

Likewise, on immigration, we live in a nation in which 67 per cent of those polled by YouGov think immigration over the last decade ‘has been a bad thing for Britain’, but which nonetheless delighted when Mo Farah told a journalist “look mate, this is my country” and cheered the daughter of a Jamaican migrant, Jessica Ennis, on to Olympic gold. The emotional picture here is significantly more textured than Labour’s recent immigration interventions have acknowledged, with people’s anxieties driven as much by identity and their own access to resources as any first order desire to pull up the drawbridge and turn the clock back.

In other words, both immigration and welfare are proxy debates where ill-considered gimmicks from the government and ill-advised apologies from the opposition won’t cut through. Instead, what Britain’s grafters are hungry for is policies that will lift their living standards in line with their deep (and wholly correct) instinct that there should be a strong relationship between what you do and what you get.

Against this backdrop, Labour does have some explaining to do, but not about the current sources of our self-flagellation. Far bigger than any of them is our failure to come to a public settlement with a globalisation that created profound insecurities at the same time as it was providing ordinary families with unprecedented access to travel and consumer goods.

While the financial crisis was the most extreme example, global forces in the form of outsourcing, wage stagnation and downward competitive pressure on pay and conditions had been buffeting those on middle and modest incomes disproportionately for years. Labour’s answer – embracing free trade while equipping the working and lower middle class to compete through investment in state education and increased higher education participation rates – was the right one economically, but we were never able to convey it emotionally, or to illuminate adequately the choices and opportunities before the British people. Globalisation is a fact rather than an option, but we never found the right words to explain why that is so – or what we intended to do about it – in the language of the kitchen table rather than the cabinet table.

In 2010, Ed Miliband’s Labour leadership campaign made much of the fact he ‘speaks human’. He does, and he will need to muster every ounce of that ability as he transitions from acknowledging people’s fears to helping us overcome them. Global interdependence – with all of its pitfalls and potential – is now a given; so the biggest question facing Labour is how to deliver decent work for our people in a context where so many of the drivers of growth lie beyond our shores. If New Labour was about renewing the left after the fall of the Berlin Wall and the electoral triumph of neo-liberalism, the task of this left generation is creating a progressive globalisation.

A comprehensive progressive agenda for the age of interdependence would need to address sustainability and the management of the global commons; the tensions between equality and growth; stability, to ensure that people’s quality of life and livelihoods aren’t threatened by conflict, shocks or crises; accountability, to close the democratic deficit which results from global problems being redefined as national ones and which leaves the sources of them completely unaccountable to the people whose lives are affected; and fraternity, so that the acceleration of globalisation doesn’t lead to further fracturing of communal life or a retreat to nativism and political extremism. When faced with this, the great progressive challenge of the age, the politics of apology seems both self-obsessed and crushingly irrelevant. The time for deconstructing yesterday is past – the fight to build tomorrow must now begin.

This article was originally published in the Fabian Review magazine.