Hope against hate

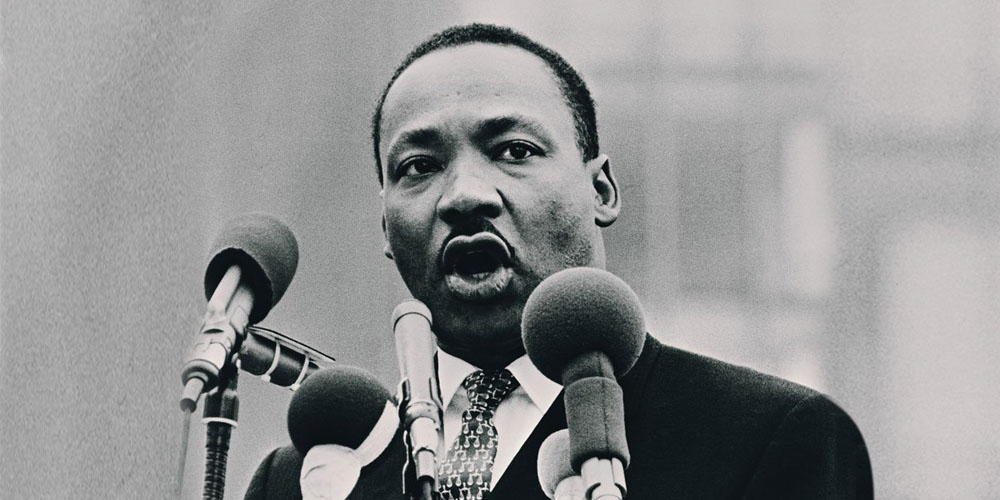

Can King's vision overcome Trump's vitriol? On November 13, 1967, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. delivered an impromptu speech in Newcastle upon Tyne after receiving an honorary doctorate from Newcastle University. King challenged his British audience to join him in confronting...

Can King’s vision overcome Trump’s vitriol?

On November 13, 1967, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. delivered an impromptu speech in Newcastle upon Tyne after receiving an honorary doctorate from Newcastle University. King challenged his British audience to join him in confronting the three great problems of his day: racism, poverty and war. Defeating those interlocking evils, King explained, required a collective effort on the part of all people of goodwill, since “we are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality.”

King’s call for unity and action echoed in my ears this weekend when I returned from Miami for an event in Newcastle to unveil plans for next year’s 50th Anniversary commemorations of King’s visit, having just witnessed one of the most divisive elections in US history.

In Newcastle, King had also insisted that it was still possible “to transform the jangling discords of our nation, and of all the nations of the world, into a beautiful symphony of brotherhood.” There was precious little of that kind of optimism around when I left America. This election was about discord not brotherhood; it turned on exploiting deeply felt antagonisms, not on appeals to unity.

Nearly a week after Trumpaggedon, “a day of infamy,” as one friend described it, riffing on president Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s description of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, vast swathes of America, not to mention the rest of the world, continue to rub their collective eyes in bewilderment. Donald Trump, the man who claimed the presidential election was rigged, is on his way to the White House with fewer popular votes than his opponent. His victory was assured by the arcane workings of an electoral college system that he once, perhaps presciently, declared a “disaster for a democracy.” The Washington outsider is packing his transition team with Washington insiders and has chosen Reince Priebus, chair of the Republican National Committee, as his chief of staff. Meanwhile, it turns out that Trump’s much-vaunted wall to keep out Mexican immigrants may after all be a fence and that not all aspects of Obamacare, once derided by Trump as the most risible domestic achievement of the worst president ever, need to be scrapped.

These are just some of the latest ironies after a campaign in which Trump won by coupling a cavalier approach to the truth with highly successful appeals to a variety of prejudices: sexism, homophobia, Islamophobia, xenophobia, anti-intellectualism, anti-Washingtonian sentiment, and various shades of racism jockeyed for pride of place in Trump’s toxic playbook. It was a cynically brilliant exercise in lowest common denominator electioneering. Trump became a conduit for widespread dissatisfaction with the political, economic and social status quo, particularly, but not exclusively, among white male blue-collar workers. Lest we forget, despite his misogyny, the predatory Trump secured 42 per cent of the female vote; despite disparaging Hispanics, he won 29 per cent of their votes. In both demographics he performed roughly as well, if not better, than Mitt Romney, the Republican candidate in 2012.

From a very different point on the political spectrum, Bernie Sanders’ spirited insurgency also represented an outlet for disgruntled Americans, this time on the left. For many progressives, Hillary Clinton had too much personal baggage to stir much enthusiasm or win. She was also associated with an intellectually moribund and morally bankrupt brand of corporate neo-liberalism that many rejected. As I watched the results come in, surrounded by incredulous Democratic party loyalists in central Florida, several people speculated about how a Sanders candidacy might have fared. “The Democratic National Committee just went out of its way to clear a path for Hillary,” one woman complained. “Bernie could have wiped the floor with Trump. He was the one with momentum. He could inspire.”

In fact, it was Trump who was truly inspirational – to those who felt neglected or patronized by the mainstream political establishment, Democrat and Republican alike. Trump offered easy scapegoats for their anger and frustration and appealed to the crassest forms of American jingoism.

Although comparisons to the nativist populism that underpinned the Brexit vote are often simplistic, there are clearly similarities. Trump, like the leave campaigners, legitimised intolerance and promoted a kind of reactionary parochialism. The abstract nostalgia of Trump’s “Make America Great Again” slogan evoked an imagined, doubtless whiter, more Christian, and more (heterosexual) male-dominated “golden age,” where the will of the people had reigned over the will of political and economic elites. Similarly, the leave campaign promised to reclaim a mythically unalloyed British identity from the clutches of immigrants, refugees, and European bureaucrats and to restore a glorious independent past. In both cases, the fall from grace was blamed squarely on a variety of convenient internal and external scapegoats.

Although there was relatively little substantive discussion of economic policy amid all the negative bile on the US campaign trail, Trump presented glib solutions – protectionism, cuts in taxes, especially corporate taxes, deregulation of finance and industry – to complex problems afflicting “Rust-Belt” and rural America that are linked to globalization, de-industrialisation and major technological changes. For example, Trump has promised to return prosperity to the coal fields by deregulating the industry and backing further exploitation of fossil fuels. Sceptical about global warming—and generally hostile to any experts whose opinions don’t accord with his own gut instincts–Trump will probably try to roll back the domestic and international clean-air agreements that Barack Obama worked so hard to secure, jeopardising the health and future of the planet, as well as that of his own citizens. No matter: such recklessness won him enormous numbers of votes. It is perhaps the greatest and grimest irony of the whole election that Trump’s top-down economic vision is unlikely to improve the lot of most of those who voted for him.

Ultimately, Trump’s success has exposed the continuing significance of major class, racial, ethnic, religious and gender divisions in the US, as well as differences between urban and rural-small town America. Nobody is spouting the sort of nonsense about a post-racial America that accompanied Barack Obama’s first victory in 2008. Indeed, some believe Trump’s triumph represents payback for electing an African American president.

“I feel like this is a scared and defensive white America’s last opportunity to stick it to the minorities,” explained one non-partisan voter in California. Every day, she has to drive her children to school past a smart pick-up truck owned by a young white mechanic adorned with a huge sticker in the shape of the United States, bearing the slogan “Fuck Off, We’re Full!” Trump has helped to make that kind of crude bigotry more acceptable, patriotic even. Still, demographics and history are against white America. “Soon,” she continued, “minorities will be the majority, and sadly, that’s a tough pill to swallow. Instead of embracing diversity, there is panic, anger and fear.” This is a national issue, but it is especially acute where economic problems and competition for resources bite hardest – and where contact with diverse populations and exposure to cosmopolitan cultures and ideas is limited.

I thought about this situation a lot in Newcastle last week, where a racially, ethnically and religiously diverse group of boys and girls from a local primary school took to the stage to sing. There are nearly 30 first-languages spoken by the kids in that school and doubtless there are moments of inter- and intra-group tensions in the playground and classroom. But on that stage, those children stood together to perform songs of hope, sharing and care for the environment. It was an uplifting moment. I think King would have approved. Maybe it was the odd glimmer of hope like this that gave him the courage to continue his struggle for social and economic justice around the world and, as he put it with a nod to the Biblical prophet Amos, to “speed up the day when all over the world justice will roll down like waters and righteousness like a mighty stream.” After the past week, it certainly offered a much needed change in perspective; a glimpse into a better, kinder, fairer world still worth fighting for.