Shaw and the sun

Founding Fabian George Bernard Shaw could often be found soaking up the rays in his rotating shed, writes Tania Woloshyn Image: Wellcome Collection Of all the images you may have come across of the illustrious Fabian, Nobel laureate and famous playwright, George...

Founding Fabian George Bernard Shaw could often be found soaking up the rays in his rotating shed, writes Tania Woloshyn

Image: Wellcome Collection

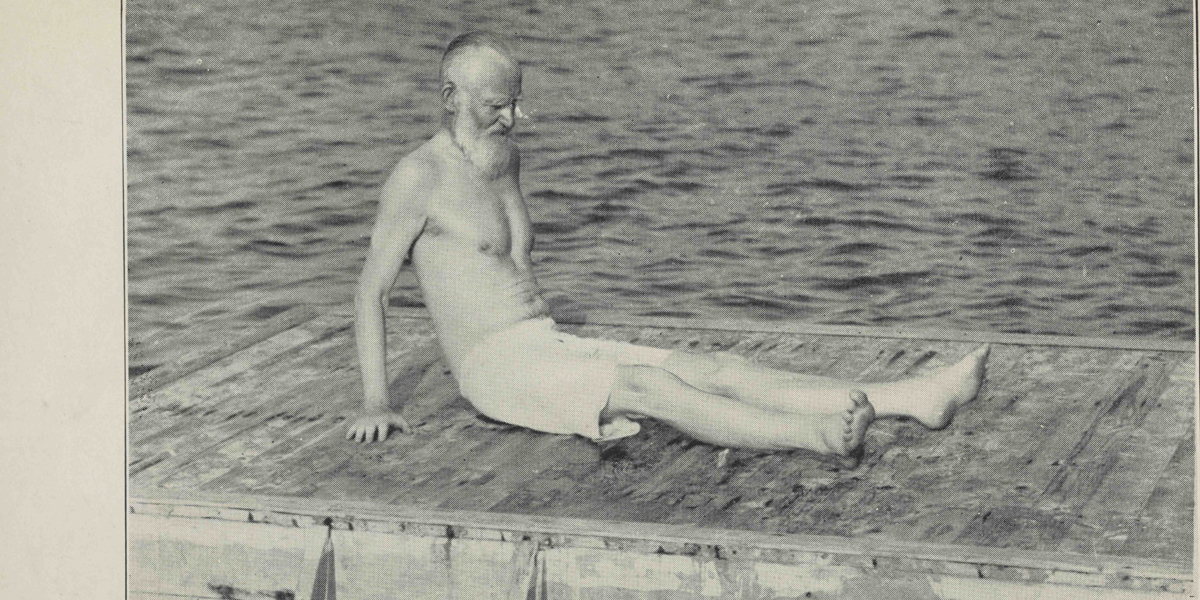

Of all the images you may have come across of the illustrious Fabian, Nobel laureate and famous playwright, George Bernard Shaw (1856–1950), I doubt you’re familiar with this one. With all the intimacy and informality of a holiday snapshot, this photograph shows Shaw poised at the edge of a wooden deck, surrounded by lapping water, and wearing rather little. He is sunbathing, of course, his skin proudly exposed to the sun’s rays, and it is a demonstration of sorts. I didn’t find it in a private family archive; I found it in a 1929 how-to book about ‘the sunlight cure’.

Light therapy was known by a number of different names during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, among them the sunlight cure, sun therapy, and heliotherapy. Sunlight could also be artificially replicated by means of electric lamps, which emanated a combination of ultraviolet, visible and infrared (heat) rays, and this was known as phototherapy. Perhaps it will come as no surprise that in the United Kingdom the artificial form, available at the flick of a switch, was more commonly used than the natural, which relied on readily available sunshine outdoors. However, as Shaw demonstrates, this did not waiver the conviction of many ardent sun-worshippers, who openly embraced the sun’s transformative rays at home and abroad.

By 1929, when Victor Dane’s populist book was published, sunbathing had become an increasingly mainstream practice. Indeed the year before The Times had even devoted a supplement to it, titled ‘Sunlight and Health’, in praise of both natural and artificial sources of ultraviolet energy. Dane’s book similarly advocated sunbathing and the use of light therapy lamps to poor and rich alike in his book. A popular promoter and controversial naturopath, he thought a suntan was the visible manifestation of ‘solar energy’ (ultraviolet radiation) stored in the body:

‘Pigmentation is a sign that solar energy has been transformed into human energy. The rays of the sun are very powerful germicides. As the skin imbibes more of these rays, it stores up a great deal of this germ killing energy… [and] once pigmentation has taken place, and a nice deep brown skin obtained, any length of exposure can be endured without the slightest feeling of discomfort. Also the body will have stored enough Solar energy… to fight against any outside disease-bringing influence which may attack him. Therefore, the first goalto be striven for by those who seek regeneration from the sun is, pigmentation. After that, health will come by leaps and bounds.’

This notion of sunbathing as a revitalising practice remains with us today, despite our awareness that ultraviolet light is a carcinogen. We may now rely primarily on little pills to get our daily dose of vitamin D – known as the sunshine vitamin – but in the 1920s and 1930s exposing one’s skin to light was considered to be infinitely more ‘natural’ (even via electric lamps). And certainly far more pleasurable than a spoonful of cod liver oil!

As with Dane, George Bernard Shaw’s devotion to the sun went beyond the holidaymaker’s occasional summer trip to the beach; it bordered on spiritualist practice. He even built a special outdoor office in his garden, a rotating shed that could be turned so as to always face the sun, much like a heliotropic sunflower. Shaw wittily named the shed after the capital city, so that when he didn’t wish to be disturbed whilst writing he could simply say he was ‘in London’. Returning to the photograph of Shaw in Dane’s book, I think it’s important to understand then that we are looking at a special kind of sunbathing. Shaw’s pose may appear relaxed but it is also reverent. He was an early champion of an offshoot of sunbathing called ‘naturism’, which complemented his devotion to vegetarianism and celibacy. Naturism, latter known as nudism, was initially conceptualised as a regenerative, moral practice, in which fresh air and sunlight were seen as powerful natural forces that could cleanse and protect the body from degenerative social ills.

A few years later, in March 1932, Shaw was one of many diverse luminaries who penned a letter to The Times’ editor advocating nude sunbathing. The other signatories included the internationally-renowned heliotherapist Dr Auguste Rollier, the psychologist John C. Flügel, the illustrator Robert Gibbings, the evolutionary biologist and eugenicist Julian Huxley, the writer and pacifist Vera Brittain, the feminist and socialist campaigner Countess Dora Russell (wife of philosopher Bertrand Russell), and the radiologist Alfred C. Jordan (founder of the Men’s Dress Reform Party, a branch of the New Health Society). Together these well-known advocates straddled the boundary between social elite and social outcast. As a Fabian, Shaw’s socialism must be contextualised as part and parcel of these other ‘natural’, healthy and morally righteous practices and beliefs.

Yet it’s also worth bearing in mind that the socio-political meanings of light’s healing properties were not particular to socialism. Bodily exposure to light was promoted by members of Labour and Conservative governments throughout the early twentieth century. So too was it promoted in fascist Italy, Nazi Germany and the communist Soviet Union. Individual and national investments in light, therefore, were not apolitical – they did not transcend competing politics, but rather were readily absorbed into them.

Soaking Up The Rays: Light Therapy And Visual Culture In Britain, c.1890–1940, by Tania Woloshyn is published by Manchester University Press