The Beveridge Report: Eight lessons for today

The Beveridge Report, the inspiration for post-1945 social security, is the obvious place to start when considering common ground between the political thinking of Labour and the Liberal Democrats. Grounded in decades of Fabian research, writing and argument the post-war...

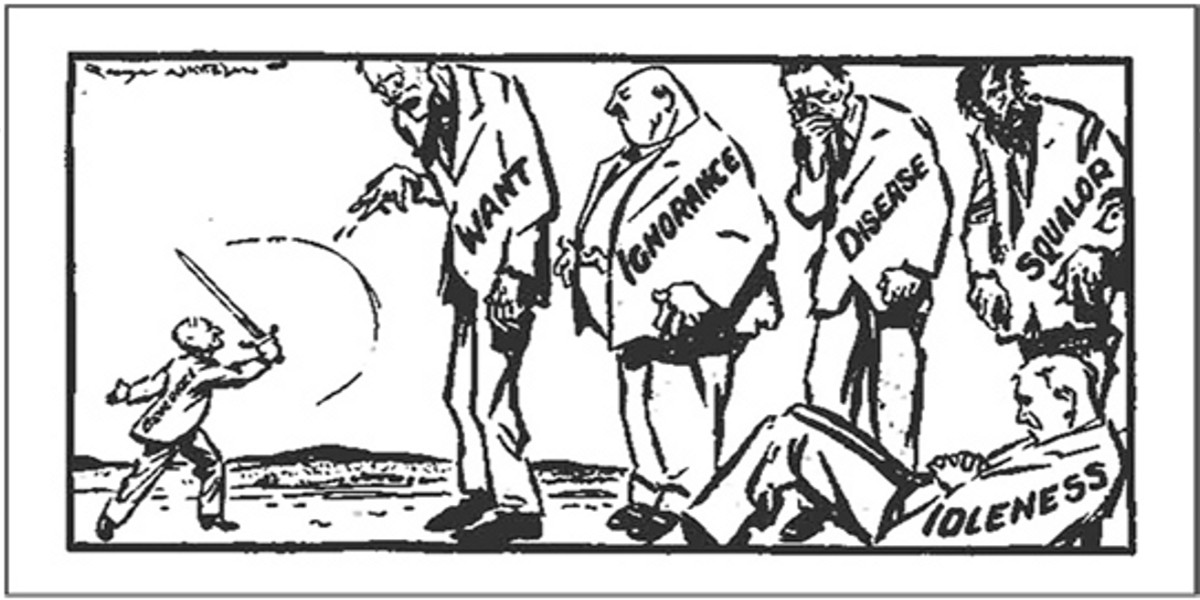

The Beveridge Report, the inspiration for post-1945 social security, is the obvious place to start when considering common ground between the political thinking of Labour and the Liberal Democrats. Grounded in decades of Fabian research, writing and argument the post-war blueprint was famously written by a Liberal and brought to life by Labour.

Today the shadow of Beveridge still looms large over British politics, and we will hear a lot more of it as we approach the report’s 70th anniversary in December. Already this year Liam Byrne has made two speeches reflecting on the legacy of Beveridge for politics today, and he is among many who single out the principle of contribution, of social insurance, as the report’s defining feature. But the Beveridge recommendations speak across the decades in more ways than that. Here are eight key points in the report which still resonate today.

- The contributory principle: Beveridge neatly asserted that ‘benefit in return for contributions, rather than free allowances from the State, is what the people of Britain desire’ and it’s hard to argue that the sentiment has changed much seventy years later. Today politicians use ugly terms like ‘something for something’ to capture the same spirit. For the left the contributory principle matters because it binds people into supporting decent welfare provision by presenting entitlements as earned rights. But it also contains a risk – that the contribution bar will be set too high and many who need help will not receive it. For example, the recent reforms to the State Pension system aimed to update contribution rules so they no longer exclude many women from full pensions.

- Universalism: Beveridge and many since have sometimes elided universal non-means-tested provision with contribution, but they need not be the same. For example Beveridge argued for contributory payments for retirement pensions and out-of-work insurance but he also proposed non-contributory Family Allowances for everyone with children. The argument for such in-work payments remain unchanged from the time Beveridge wrote: ‘if children’s allowances are given only when earnings are interrupted and are not given during earning also, two evils are unavoidable. First, a substantial measure of acute want will remain among the lower paid workers as the accompaniment of large families. Second, in all such cases, income will be greater during unemployment or other interruptions of work than during work.’ Today Child Benefit remains but we also have tax credits and soon universal credit to overcome poverty and earnings ‘traps’ with payments continuing well up the earnings distribution – progressive universalism, as Gordon Brown called it. Today many on the left worry that removing Child Benefit even from very high paid families could undermine solidarity for child-focused welfare.

- Adequacy: Beveridge found that welfare provision where ‘benefits amount to less than subsistence’ was one cause of the giant of ‘want’. His insurance scheme was therefore designed to ‘guarantee the income needs for subsistence in all normal cases’. This principle is being rediscovered in the design of the state pension. The 2012 Queen’s Speech included a bill to introduce a higher flat-rate state pension for all future retirees, paid at a level in line with contemporary measures of ‘adequate’ income (this Liberal Democrat policy accelerates a plan introduced by Labour in government). Gordon Brown’s tax credit system aimed to do the same for families with children, albeit on a means-tested basis. But this principle has been totally abandoned when it comes to people before retirement without children. After decades where we have indexed the main out-of-work benefits to inflation rather than earnings they are totally inadequate to lead a normal, healthy lifestyle.

- Hypothecation, of a sort: Beveridge built on previous insurance schemes by presenting contributions as hypothecated for the provision of welfare provision (though not necessarily to specific contributory allowances). But he did not support a ring-fenced system where inputs and outputs should match. Originally the taxpayer was expected to pay a large share as well as individuals and employers. Perhaps more importantly, his proposals embodied what can be called ‘soft’ hypothecation: the introduction of improved provision came hand-in-hand with the announcement of revenue-raising measures. Even this form of hypothecation has traditionally been resisted by the Treasury, but was famously employed by Gordon Brown in 2002 to raise National Insurance to improve the NHS (following the work of the Fabian Commission on Taxation and Citizenship). Today, the principle of matching new spending programmes to revenue streams needs to be revived, simply because there is no prospect of new welfare provision from general taxation. The best example is the funding of social care, where the parties are in deadlock over the best funding source for spending reforms almost everyone supports.

- Conditionality: An ugly word for an old idea, that social security entitlement should be dependent on your current actions not just past contributions. Beveridge said unemployment benefit ‘will normally be subject to a condition of attendance at a work or training centre after a certain period’ while disability benefit would be paid ‘subject to acceptance of suitable medical treatment or vocational training’. In our collective memory the left has forgotten that the idea of conditions for support does not just trace its lineage to the Work House but also to the mutual insurance fund. Over the last decade the reintroduction of conditionality with respect to disability benefits was initially greeted with opposition in principle, but this has been slowly displaced by concern with fair implementation based on people’s personal circumstances.

- Longevity: Population ageing and the rapid growth in the pensioner population are often presented as novel policy challenges. But the Report anticipated our contemporary debates, recognising that ‘persons past the age that is now regarded as the end of working life will be a much larger proportion of the whole community than at any time in the past [making] it necessary to seek ways of postponing the age of retirement from work rather than of hastening it’. Beveridge understood that state pension provision ‘represents the largest and most rapidly growing element in any social insurance scheme’ so the fact that we today spend two-fifths of all welfare on state pensions should not be seen as shocking or novel. Beveridge proposed that the pension age be a minimum age of retirement but wanted to see pension rates ‘increased above the basic rate if retirement is postponed’ – an idea reintroduced by Labour’s pension reforms, but seldom taken-up in practice. The raising of the pension age may be regrettable for all sorts of reasons, but we can hardly suggest it is a betrayal of the Beveridge settlement, given that male life expectancy at 65 has roughly doubled since 1943.

- Private provision: A key dimension of Beneridge that many on the left have forgotten is the report’s keen endorsement of personal saving and insurance as an addition to good public welfare. In outlining its key principles the report argued that ‘the State in organising security should not stifle incentive, opportunity, responsibility ; in establishing a national minimum, it should leave room and encouragement for voluntary action by each individual to provide more than that minimum for himself and his family.’ This principle was a key consideration in the design of Labour reforms such as the Child Trust Fund and the Savings Gateway (both scrapped by the coalition), the new state pension and the recent proposals for social care advanced by Andrew Dilnot.

- Housing costs: A final salutary thought. Beveridge was unable to resolve ‘the problem of rent’ and come up with a fair way of supporting people with housing costs under a contributory, universal system. The costs of housing were and are so variable that any flat-rate subsidy would either cause real hardship or give some money they had no need for. Beveridge wrote ‘in this as in other respects, the framing of a satisfactory scheme of social security depends on the solution of other problems of economic and social organisation’; problems familiar today like high unemployment, falling earnings, inadequate housing supply and huge regional dispaprities. Housing benefit remains the ultimate economic ‘stabiliser’ patching-up the failings of our unequal society. Its rapidly rising cost is a reflection of our economic failure not the failings of the people who need to rely on it.