Beveridge and the five giants – 75 years on

75 years on from the publication of the Beveridge report the world has changed enormously, and so have some parts of the welfare state, writes Nicholas Timmins

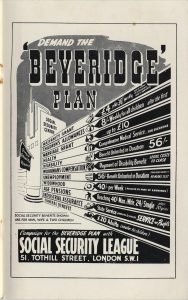

December 1st is the 75th anniversary of the Beveridge report. The founding document of the UK’s modern welfare state.

December 1st is the 75th anniversary of the Beveridge report. The founding document of the UK’s modern welfare state.

And it is an anniversary of which the Fabians, as much as anyone, can be proud. After all, it was Beatrice Webb’s minority report to the Royal Commission on the Poor Law that is widely seen as one of the first, decisive, calls for a free public health service, even if it was to take almost 40 years for the National Health Service to come into existence.

It was the Webbs who founded the London School of Economics, of which Sir William Beveridge became director (even if his not infrequent arrogance caused a revolt by the staff in the favour of a proper constitution).

And before that it was the Webbs who introduced him to a younger Winston Churchill, at the time a minister in the great reforming Liberal government of 1906 to 1914. The one that introduced the UK’s first statutory, compulsory, but not comprehensive, insurance schemes for sickness and unemployment, creating what came to be dubbed “the ambulance state” – the precursor to the modern welfare one.

This was a time when Churchill was proclaiming Liberalism to be “the cause of the left out millions” with statutory insurance bringing “the magic of averages” to their rescue. And on the way, Churchill’s aside – that “I refuse to be shut up in a soup kitchen with Mrs Beatrice Webb” – was evidently no barrier to Beveridge’s appointment, which saw him, with Churchill, create the first Labour exchanges as well as the first unemployment insurance.

Beveridge, of course, was not a Fabian. He was more of a Liberal and indeed briefly became a Liberal MP. His mighty report in 1942, in the middle of the second world war, called for the famous attack on “the five giant evils” that stood on the road to post-war reconstruction.

Upon Want – by which he meant poverty. Upon Disease “which often causes that Want”. Upon Ignorance, “which no democracy can afford among its citizens”. Upon Squalor. And upon Idleness “which destroys wealth and corrupts men.” And it fell to Labour – Butler’s 1944 education act, and the introduction of family allowances aside – to construct the five giant services and policies aimed at tackling the five giants. The NHS. A big new house building programme, that was slow to get going but was followed by slum clearance. The policy of full employment, which governments up to the late 1970s sought to honour. And the new system of social security that Beveridge recommended, and which, in fact, formed the core of his report.

But the social security system that Beveridge designed and Labour adopted – with some changes to his original plan along the way that did it no favours – was always a minimalist one. There to prevent poverty, with flat rate contributions in return for flat rate benefits, rather than the earnings-related approach that most other major European countries adopted after the war. These, at least for a time, tended to preserve one’s place in society, rather than the individual falling back to a basic floor – “subsistence” or enough to prevent poverty – when hard times were hit.

And Beveridge was as keen on responsibilities as well as rights. He declared there should be what we would now dub “welfare to work” programmes when individuals were unemployed for any length of time – he suggested six months in normal times. They should be required to attend a work or training centre “to prevent habituation to idleness and as a means of improving capacity for earning” – although it was not be until the 1990s, after the fracturing of full employment, that those were to arrive.

He wanted a “something for something” arrangement – “contributions in return for benefit” – rather than a plan “for giving to everybody something for nothing.” And he was clear that in providing security – indeed “social security” – the state “should not stifle incentive, opportunity, responsibility; in establishing a national minimum, it should leave room and encouragement for voluntary action by each individual to provide more than the mimimum for himself and his family.” Thus, for example, the basic state pension was there as a platform on which private saving could be built.

Today, of course, the world has changed enormously, and so have some parts of the welfare state – a phrase, incidentally, that Beveridge hated and refused to use, disliking its “brave new world” and ‘Santa Claus’ connotations. We currently have, once again, something nominally pretty close to full employment, with the unemployment rate at its lowest for 40 years. But with the gig economy and zero-hours contracts that feels very different from the days of full-time male employment in the 1940s and 1950s (and it was, overwhelmingly, male employment, with most married women being ‘housewives’).

The NHS is still recognisable as Beveridge’s ideal. A service “without charge of any kind”, other than prescription charges in England (but not elsewhere in the UK), even if bits of it – the provision of spectacles, for example, and much dentistry – have fallen off the edges and become largely privatised.

The single state pension is becoming again what Beveridge envisaged – a “just about liveable” platform on which private saving can again be built, though after a 40 year detour that saw attempts to build an earnings-related platform on top come and go, and a 30 year period when its value was being eroded steadily away. Private pension saving, has of course, been decimated, although the arrival of auto-enrolment, if governments stick to raising the amount that goes in, may yet provide some level of revival in that.

Education, both schooling and higher education, has been transformed, even if training and vocational education remains one of the UK’s persistent failures. And housing remains, as we all know, a major problem, though a different kind of problem to the one Beveridge wanted solved.

The biggest single shift has been in social security, where the link between national insurance contributions paid and benefits received has become vanishingly small, with the exception of the basic state pension – and even here there are significant qualifications.

Means-tested benefits – tax credits, housing benefit, the child tax credit, and, in time, universal credit – now stretch up the income scale to those in work. Inconceivable in Beveridge’s day. But the result of both the Conservatives and Labour recognising in the 1990s that – in a world where globalisation was forcing down the wages of less skilled jobs – it was better to use benefit money to subsidise people to be in work, rather the paying them benefit on condition they did not work. And amid widening income inequality, it has probably become impossible to rebuild the national insurance base for those of working age. Those in low paid work require tax credits to keep them going, so cannot pay higher contributions. And those higher up the income scale more obviously do not “need” the benefits, which was always the old argument against them.

The challenges today are different. Rather than worrying about a growing and ageing population, the worry in Beveridge’s day was a declining population as the birth rate in the 1930s had plummeted. To the point where he declared that “with its present rate of reproduction, the British race cannot continue.”

A key issue back then was poverty among the elderly. Today pensioners – always recognising that 3 million of them depend on the pension credit – are the household type least likely to be in the bottom fifth of the income distribution. The problems now are that being in work no longer guarantees that a family gets above the modern definition of the poverty line, with 60 per cent of children in poverty being in working families. And inter-generational inequality – where it is the future of the young that parents and grandparents fret about.

One other big change is that back in Beveridge’s day tax rates were high by modern standards, but tax thresholds too were much higher. To the point where many in the working class and indeed some in the middle class, if they had children, paid no income tax at all. The steady move of taxation down the income scale, in order to pay for the welfare state, was one reason why support for it eroded across the 1960s and 1970s.

These days we have the remarkable paradox of much outrage at the tax avoidance undertaken by the better off revealed in the Paradise Papers, but alongside it the opinion poll finding that almost half of UK adults, and 43 per cent of Labour voters, would happily take a “non-illegal” way of “dramatically” reducing their tax bill. Even as other polling shows that the public wants a strong NHS and well-funded education. Which is another major challenge for the welfare state, leave aside the lengths to which Apple, Google, Amazon and like go to reduce their tax liabilities.

And then there is the possibility that IT and automation are going to destroy zillions of jobs, white collar as well as blue. And the argument that the welfare state will therefore itself have to change so radically that it will have to provide a basic income for all. Beveridge, with his something for something approach, would not have approved of that. And personally I am highly sceptical that the British electorate would ever vote for the sorts of levels of taxation that decent level of basic income would require.

But all that is for another day. Right now, Fabians should be celebrating the fact that for all the changes to it – holed and shrunk in places, suffering deeply from austerity, but with new limbs added in others – we do still have a welfare state. And thinking hard about what needs to be done to preserve it.

Nicholas Timmins is the author of the award-winning The Five Giants: A Biography of the Welfare State, a fully updated version of which was published on November 2 by William Collins