2014, Labour’s year of…Ending digital exclusion

Governments across the world are embracing digital technology. The prime minister even live-tweeted his latest ministerial reshuffle. But we would be wrong to assume that everyone in our society is enjoying the greater choice, better job prospects, and easier access...

Governments across the world are embracing digital technology. The prime minister even live-tweeted his latest ministerial reshuffle. But we would be wrong to assume that everyone in our society is enjoying the greater choice, better job prospects, and easier access to information that fast internet access brings. There are still numerous obstacles to getting online, and removing them goes to the heart of the inclusive politics that a one nation Labour government would bring to the country.

In his excellent analysis of the problem, ‘Across the Divide: Tackling Digital Exclusion in Glasgow’, Douglas White of the Carnegie Trust focussed his research on my home city and found that an astonishing 40 per cent of residents are still offline, nearly double the UK average of 24 per cent. Other parts of the UK, such as north-east England and Northern Ireland have similarly poor levels of internet usage. As the government shifts to a ‘digital by default’ position in its provision of public services, I am worried that those in this offline demographic are being forgotten by both the public and private sectors.

Low internet usage is not due to a lack of broadband access. Indeed, the Treasury announced plans earlier this year to make superfast broadband available to 95 per cent of the country by 2017, and has invested considerable sums in strengthening rural broadband infrastructure. The problem is one of take up; the Carnegie Trust report found that there are a variety of reasons for people not using the internet: preferring to do things by phone or face to face; concern over online safety and viruses; the cost, and not wanting to sign a contract; the difficulty of learning how to use the internet; spending money on other things. These boil down to two basic concerns; fear of the online world, and the cost of getting online. The government have so far done little to tackle either of these problems.

The benefits to being online are clear. Internet access facilitates easier communication with friends and family, better shopping and utility deals, wider job searches, online training opportunities and access to local and national public services. But these are rarely communicated to the most excluded groups, especially pensioners and non-working adults living in social housing. There are various not-for-profit training organisations that focus on digital exclusion, and their work is to be applauded.

But given the huge public investment made by the Government in rolling-out superfast broadband across the UK, why is not even a small portion of that funding being set aside for digital literacy training and support on a larger scale? It appears that the government has failed to learn the impressive lessons from the recent switch to digital TV, which included a centrally funded programme to ensure maximum take-up throughout the country.

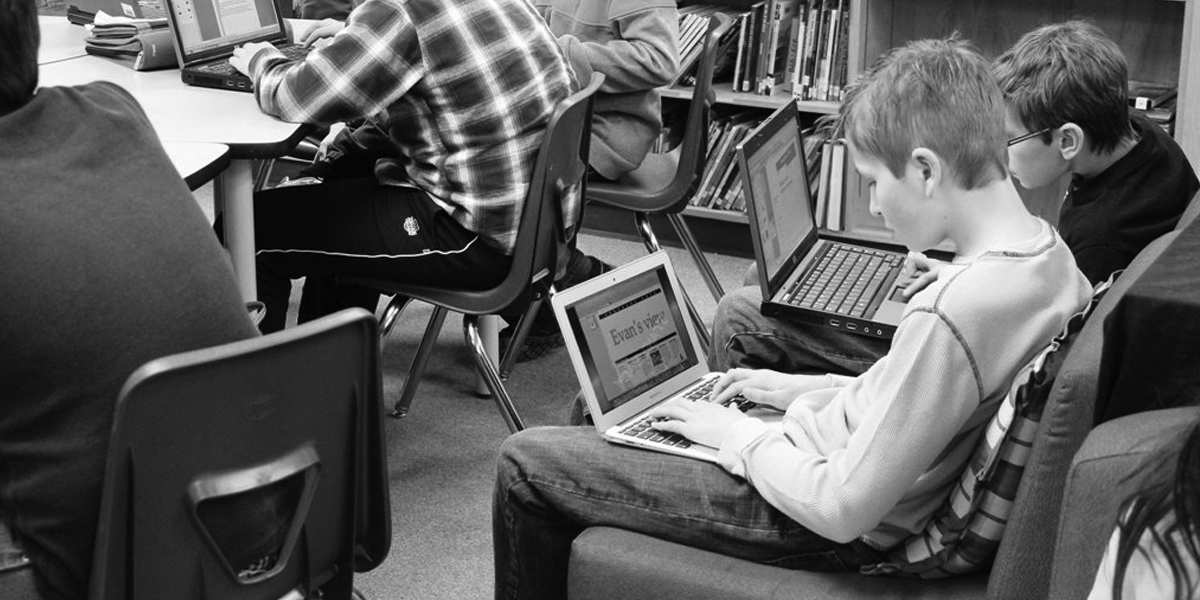

Such a programme could fund community projects in the most digitally excluded parts of the UK, such as the example set by Liverpool, where a group led by the city’s local council increased digital literacy substantially in very little time. The Carnegie Trust report recommends the creation of local role models, or ‘digital champions’, who would take a leadership role in communities with low levels of online access. In the USA, the Net Literacy organisation operates a model in which student volunteers deliver training to those without internet skills, already reaching 250,000 individuals since it was founded in 2003. This is the kind of vision we need for improving digital skills in the UK: low cost, easy to replicate, and offering rewards for both trainee and trainer.

The question of how to fund access itself – from the broadband coming down the cable to the physical computer it is used on – is perhaps a trickier question. Thankfully, hardware costs have been coming down for years, and the advent of tablet computers means that laptops and basic desktop computers are affordable and within reach of those on low incomes. A year ago, Ian Duncan Smith said his department was looking at the possibility of ‘social housing tariffs’ for broadband, but this does not seem to have gone anywhere. Housing associations in Glasgow have recently piloted a scheme in which subsidised broadband is provided to residents along with tablet computers able to connect to Wi-Fi points in their properties. This is perhaps not a scalable solution, but such a bold intervention by those on the coalface of social housing policy shows that some problems need a radical response.

Combining top-notch training with low-cost hardware and internet access is the key to closing the UK’s digital divide. The Government must commit to a strategy for reducing digital exclusion as well as improving infrastructure, or it risks leaving a large section of our society behind.