Turning the tables

Injustice in our labour market is home-grown and can be fixed if we give workers power, argues Faiza Shaheen.

Employment not only takes up the majority of our waking hours and defines our quality of life, it is inextricably linked to both our physical and mental health. In other words, when the labour market stutters, we all stutter. In recent decades our labour market has become a major source of inequality and societal problems. Work is no longer a guaranteed route out of poverty. The Joseph Rowntree Foundation estimates 3.7 million workers are living in poverty and the majority of children living in poverty are to be found in a working household. Real weekly wages remain lower today than they were before the financial crisis.

Meanwhile, precarity is seeping up the income distribution ladder to the extent that financial insecurity has become the new normal. CLASS research conducted earlier this year found that up to three quarters of the working population are of the opinion that ‘the economy is not working well’ for them. We spoke to union representatives that told us shocking stories of mental health workers themselves suffering from mental health problems. The same study found that more people than not felt that employee voice in the workplace was diminishing.

Many of us will agree that there is rot beneath the headline employment figures that tell us our labour market is performing well – but we remain split on how to tackle the problem. After more than a decade of working on the issue, I’ve come to see that the challenge of re-shaping the labour market requires far more than the ‘sticky plaster’ policy we’ve become accustomed to – we need an overhaul of power in the workplace.

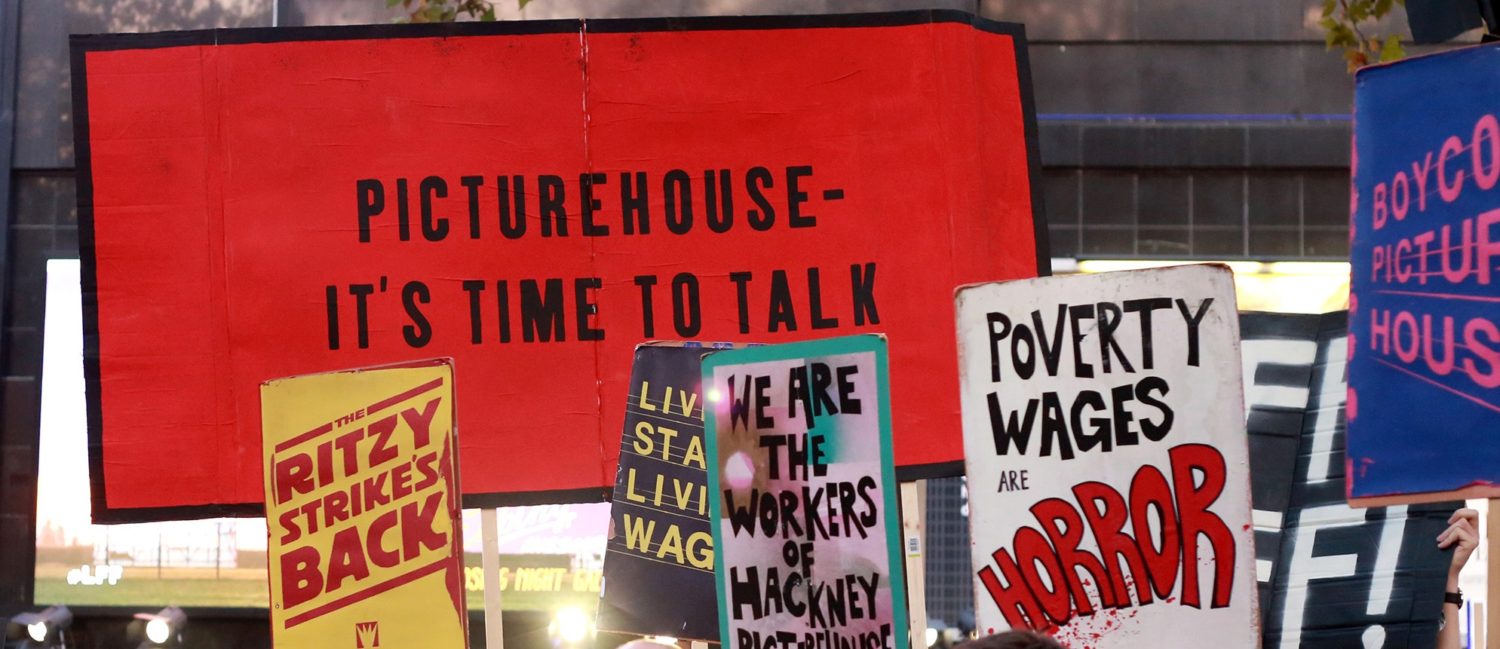

It is not a coincidence that as low pay and precarious working has soared, the role of trade unions has diminished. Decades of draconian legislation have impinged upon fundamental workers’ rights so that today trade union density stands perilously low. At the same time, legal loopholes and exploitative employers leave millions of workers in a position where they cannot challenge their bosses over infringements of the minimum wage and other basic entitlements.

Many will be reading this and wondering why I’m starting with the issue of power and unions. The mainstream narrative has been that it is globalisation alongside technological change that has resulted in growing income inequality and declining labour market conditions.

The basic explanation of how globalisation is driving economic inequality is that opening up economies to developing countries undermines the position of low-skilled workers in richer nations. On the other hand, skill-intensive sectors become more concentrated in higher-income countries where a greater proportion of the population is highly qualified. Fewer opportunities for those without many formal qualifications, alongside more opportunities for those with graduate skills, lead to a growing gap in labour market fortunes.

Despite its popularity as an explanation for increased income disparities, the data on globalisation does not suggest that it is the central factor. The Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development’s statistical analysis found that higher imports from low-income countries only caused wage dispersion in countries with weaker employment protection legislation. Furthermore, the lowest wages and poorest working conditions are not found in sectors where jobs are at risk of flight overseas to cheaper labour markets, but rather in the care and hospitality sectors where jobs, by their nature, remain within the domestic economy.

The inability of globalisation to explain the growth of economic inequality has a silver lining – it opens up the space for domestic policy discussions and solutions. If globalisation were key to driving economic inequality, then tackling it would require measures to reverse globalisation – while this maybe President Trump’s approach, most consider it undesirable.

The scope of change brought about by automation and technological advancements demands serious policy attention now and into the future. Yet here too we find reason for hope – after all, all high-income countries have been subject to these currents of change, yet many have managed to avoid a dramatic decline in workers’ rights and conditions.

We are not simply at the whims of globalisation or technological innovation, we can choose to shape the impacts of these drivers. The state of the labour market is a policy choice. Uber can be a co-operative owned by its drivers!

Where next for the UK labour market?

Henry Ford famously said “there is one rule for the industrialist and that is: make the best quality of goods possible at the lowest cost possible, paying the highest wages possible.” It seems that this logic – one of making products that your own staff can afford to buy – has been lost in the modern age. A new vision for our labour market must replace our current race-to-the-bottom approach on pay, workers’ rights and regulation. For too long the state has shirked its role in supporting robust labour market institutions. As a consequence, the imbalance of power between employers and employees (as well as between capital and labour) has tilted too far toward the former. Where to start? The first and most crucial step is addressing the lack of power and voice workers have in the workplace. While the right to join a trade union, right to strike and right to collective bargaining are set out in a number of international declarations, the UK policy environment is far from conducive to the realisation of these rights. The Trade Union Act 2016 forced further cumbersome regulations onto trade unions in the form of a 50 per cent turnout for industrial ballots to be deemed legally valid and a 40 per cent support threshold among all workers eligible to vote. The PCS union was recently denied the right to strike after their highest ever yes vote and turnout in history because of this legislation.

New trade union legislation must be accompanied with active promotion of collective bargaining at a sectoral and firm-level. The Institute of Employment Rights has called for a Ministry of Labour, headed by a minister with a seat at the cabinet table to provide a voice for the UK’s 32 million workers and the power to roll out sectoral collective bargaining. An important component of this is to establish Sectoral Employment Commissions (SECs) to regulate minimum terms and conditions within specific sectors of the economy.

Further reforms to outsourcing and public procurement practice would also bolster the trade union movement. Amongst the 20 point plan for workers’ rights in the 2017 Labour manifesto, there were calls for public procurement contracts to only be awarded to companies that recognise trade unions. To avoid further infringements around workers’ rights and the ‘fissured workplace’, the TUC have called for a system of ‘joint and several liability’ so that companies have greater legal responsibility for infringements of workers’ rights across their supply chain and other business entities.

Another way to bolster worker voice is to have workers on boards. There is a whole variety of evidence that this measure promotes good corporate governance and some form of employee representation at board-level remains the norm across Europe. CLASS research has previously highlighted the need for trade union involvement in the process of establishing workers on boards and the idea had gained traction. While running for office, Theresa May pledged that we were “going to have not just consumers represented on company boards but workers as well.” Unfortunately, the idea has since been scrapped.

It is important however that workers on boards are not used as a tool for circumventing union involvement in the workplace. This policy should be implemented alongside appropriate collective bargaining mechanisms. Finally, changes should be made to the law that currently prioritises maximising shareholder value in the running of companies at the expense of all other stakeholders.

We also need to be thinking about alternative models of ownership. Almost half of UK company equity is owned abroad and just over 12 per cent is owned by individuals. Transferring businesses to cooperative ownership requires a sustained shift in policy towards an environment that would allow co-operatives to thrive. The work being done in Preston on local community wealth building is a good example of one successful approach.

In light of automation and the pressure it may put on job numbers, we also need to consider what we are spending our hard earned wage packets on. Reimagining the labour market means also reimagining the housing market as well as the welfare system to ensure we support people when they need it.

Compared to many of our European neighbours and our own past, this ‘to do’ list is not particularly radical. The main task is to convince people that a better world is not only desirable, but possible.