Labour’s rural challenge

Labour has a mountain to climb to win the next election. But there is no route to power without rural communities, writes Ben Cooper

Labour has a rural problem. The 2021 local elections saw Labour underperform in rural areas, compared to the rest of the country: Labour’s share of the vote was just 23 per cent in wards classed as ‘village or smaller’, compared to 45 per cent in wards in ‘core cities’. But this is just the latest evidence of a longstanding problem.

Since Labour historically underperforms in rural communities, it may be tempting to suggest they and their voters are out of reach, and not a priority for resources. If Labour wants to win an election, you could argue, the party should look elsewhere. But this is wrong: Labour must win rural voters to win the next election; and Labour can win rural voters – with a bit of work.

A history of rural underperformance

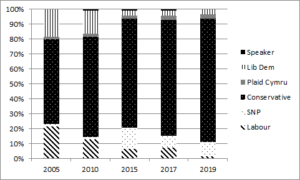

Labour currently holds just two out of 124 constituencies in Great Britain that are classified as ‘village or smaller’ – i.e. where at least a plurality of voters live in what would be classified in the census as ‘rural output areas’ (Hemsworth and North Durham). It currently holds no seats where a majority of voters live in rural output areas. Just 2 per cent of ‘village or smaller’ seats have Labour MPs – a historic low, compared to 82 per cent held by the Conservatives, 10 per cent by the SNP, and 3 per cent by Plaid Cymru (see Figure 1). For a party that seeks to represent and govern the whole of Great Britain, representing a smaller share of rural Britain in Parliament than the SNP or Plaid Cymru shows the scale of Labour’s current underperformance.

Figure 1: After the 2019 elections, Labour now represents a smaller proportion of rural seats in Great Britain than any other party in Parliament.

This means that less than 1 per cent of MPs in the 2019 Parliamentary Labour Party (PLP) represent rural seats, compared to 28 per cent of the Conservative parliamentary party. Back in 2005, twenty-seven Labour MPs (or 8 per cent of the PLP) represented rural seats. But the proportion of the PLP representing rural seats has decreased in every election since 2005.

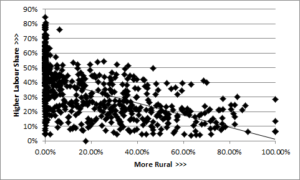

Across all 124 rural seats, Labour’s vote share is very low. In 2019, Labour won around 50 per cent of the total vote in ‘core city’ constituencies, both in and outside of London, while securing just 19 per cent of the total vote in rural seats. Looking at all seats in Great Britain, we can see that the more rural a constituency, the lower Labour’s vote share was in 2019 (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: The more rural a constituency is, the lower Labour’s vote share is in the 2019 election.

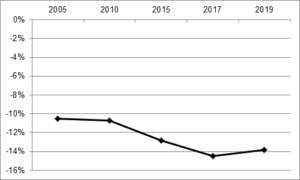

Labour’s performance in rural seats relative to its national (Great Britain) vote share is very poor: there was a 14 percentage point gap between the party’s national vote and its rural vote in 2019. And this isn’t just a feature of the latest election (Labour’s worst election defeat since 1935). Labour’s performance in rural constituencies has been poor for a long time and has worsened since 2010 (see Figure 3). Despite gaining thirty seats and increasing its vote share by 9.9 per cent in the 2017 election, Labour’s underperformance in rural areas increased by around 2 percentage points compared to 2015. Even as the party was seeing relative success across Great Britain, it wasn’t seeing similar gains in rural areas.

Figure 3: The percentage point difference between Labour’s share of the vote across Great Britain and its vote share in rural constituencies has increased since 2005.

Following the 2017 election, a Fabian Society report, Labour Country, warned that ‘despite Labour’s strong performance … it risks becoming electorally and culturally adrift in rural areas’. Since then, things have only got worse.

Labour’s underperformance in rural areas is part of a broader trend, with its vote concentrated increasingly in London and other major cities. The party has a non-metropolitan problem as it also struggles in towns, especially those that aren’t part of a large conurbation, as well as rural areas. It means that Labour isn’t just behind in the polls, its voters are distributed inefficiently across the country.

This trend risks becoming self-fulfilling; it will be more difficult to reverse as the party’s connection with rural areas becomes weaker and there are fewer Labour parliamentarians to speak up for rural communities within the party.

Why it matters

This rural underperformance matters because there is no route to government without representing rural communities and improving Labour’s vote share in rural seats. And unless we enter government, we cannot tackle the poverty, inequality and cuts to public services that blight rural areas.

Following the 2019 election, Labour was 123 seats short of a majority. The Fabian Society has suggested the party should consider targeting 150 constituencies where the swing required is less than 13 percentage points. Of these, twenty-one are classified as ‘village or smaller’ (i.e. ‘rural’):

They are found mainly in Wales, Scotland and the North (see Figure 4)

- Fourteen are currently held by the Conservatives, four by the SNP, and three by Plaid Cymru

- Seven were lost by Labour in 2019 (like Sedgefield); one was held in 2015 but lost in 2017 (Copeland); three were lost in the 2015 election in the SNP landslide (like Airdrie and Shotts); four seats elected a Labour MP in 2005 but have not done so since (like Arfon); and six Labour has not won since 2001 or before (like Preseli Pembrokeshire)

These constituencies are not complete strangers to Labour representation: many voted Labour recently and their history shows they are winnable in the future.

With the next election likely to take place on new boundaries, the exact constituencies Labour should target could be different.

Figure 4: The twenty-one rural seats that Labour should target are found mainly in Wales, Scotland and the North.

However, Labour must not just focus on rural constituencies, but on rural voters. There is a difference between what we think of as rural seats (where at least a plurality of people live in a rural output areas) and constituencies which aren’t rural as a whole, but still have many rural voters within them. In these constituencies, winning even a small number of rural voters could make the difference between electing a Labour MP and not.

There are rural voters in 472 seats across Great Britain, ranging from seats where every resident is ‘rural’ (like Na h-Eileanan an Iar) to seats where under 5 per cent are ‘rural’ (like Redcar). Only thirty-four seats out of the 150 that Labour needs to win have no rural residents at all, mainly in London, other cities and large towns, from Kensington to Great Grimsby.

Clearly, winning the rural vote won’t be a game-changer in all these seats. But if we just look at constituencies where at least 25 per cent live in rural communities, this includes fifty of the 150 seats Labour should consider targeting (including the twenty-one seats that are classified as ‘village or smaller’, previously discussed). Of these fifty seats:

- They are found in every region and nation in Britain except London and East England, with over half found in Wales, Scotland and Yorkshire and Humber

- Thirty-six are currently held by the Conservative Party, eleven by the SNP, and three by Plaid Cymru

- Twenty were lost by Labour in 2019 (like Don Valley); two were held at the 2015 election but lost in 2017 (like Middlesbrough South and East Cleveland); six seats were lost in the 2015 SNP landslide (like Livingston); nine seats elected a Labour MP in 2005 but have not done so since (like Dover); and thirteen seats Labour has not won since 2001 or before (like Shipley).

Figure 5: The fifty seats Labour needs to win where rural voters could make the difference are found in every region of Britain except London and East England.

Winning votes in every part of rural Britain is critical to provide the parliamentary majority necessary to govern, but especially in Scotland, Wales and the North. A Labour majority requires uniting seats traditionally seen as rural, like Carmarthen East and Dinefwr (where over 85 per cent of people live in rural communities) and seats traditionally seen as urban but which have a rural population, like Shrewsbury and Atcham (with 30 per cent living rurally).

So, Labour has to broaden its appeal to rural voters and reduce its underperformance in those places if it wants to enter government and secure a mandate for change. But Labour faces a significant challenge in doing so.

The challenge

To govern again, Labour needs to get elected in seats that are different from those it currently represents. Rural seats are not just different because of their rural character. Compared to the seats it won in 2019,[i] Labour’s fifty rural target seats have:

- A larger proportion of over-65s, with 22 per cent of the population aged over-65 compared to 14 per cent in Labour-held seats.

- A larger proportion of homeowners, with 69 per cent of people owning their home compared to 54 per cent in Labour-held seats.

- A lower proportion of 16- to 64-year-olds educated to degree level and above, with 40 per cent educated to that level compared to 45 per cent in Labour-held seats.

So, the rural seats that Labour needs to win are demographically different, and in ways that clearly negatively affect Labour’s vote share. Generally, older voters, non-graduates and homeowners have swung against Labour in recent elections.

However, it is incorrect to say that Labour’s rural problem is because of these factors alone. The party does not underperform just because those living in rural seats are older or because they have a higher level of homeownership. As Labour Country argued, ‘rural communities … have an aversion to Labour that goes beyond what might be expected on the basis of demographics’. This 2018 report found that the Conservatives had a significant lead with working-class rural voters (which is likely to have widened since) and, crucially, Labour did much worse with young rural voters compared to young urban voters.

Labour’s lack of appeal stems from a widespread perception that the party is out of touch with rural life: 2017 polling for the Fabian Society found that 61 per cent of respondents in rural England and Wales believed Labour did not understand people who live in their local area and 57 per cent believed the party did not share their values, compared to 39 per cent and 40 per cent respectively in urban Great Britain. For many rural voters, Labour ‘is a party of the cities, by the cities, and for the cities’. Even Labour councillors and members agreed, with one, interviewed for Labour Country, saying that the party ‘did not have a clue about the countryside’.

But there is an opportunity here too: the rural voters we surveyed in 2017 didn’t trust the Conservative Party much either. Many Conservative voters in rural areas believe that the Conservatives do not understand people who live in their area, and that they do not share their values. This could be a reason for hope: a significant part of the Conservative Party rural vote appears to be softer than assumed.

This echoes the ‘Red Wall’ analysis that shaped the last election – that there is a cultural aversion towards Labour in rural areas, as there is for Red Wall voters towards the Conservatives. As a result, Labour underperforms with rural voters, just as the Conservatives did with Red Wall voters until 2019. There are fewer rural voters who could shift election results, and there isn’t yet a similar catalysing experience which could dispel negative perceptions of Labour, like Brexit did for the Conservatives in Red Wall seats. Nonetheless, there is an opportunity for Labour to dispel negative perceptions, pick up seats, and place the Conservatives on the back foot in its ‘heartland’ constituencies. However, unlike other electoral strategies, such as winning the ‘Blue Wall’ or a progressive alliance, securing the votes of rural Britain will mean appealing to leave-voting Conservatives and swing-voters, and not focusing on the electorally insufficient Green, Lib Dem and Tory Remain voters – many of the latter have proven, repeatedly, that they won’t ever vote Labour.

A party of rural Britain?

To win a majority at the next election, Labour has to reject fears that the rural vote is out of reach, and become a ‘one nation’ party that seeks to represent rural Britain as well as towns and cities. It is also important, as a matter of principle, for Labour to present itself as a party of the whole country, against a Conservative Party increasingly content to pit different areas and people against each other.

There is a strong policy agenda that can unite rural and urban constituencies. Polling in 2019 found the top three issues for rural voters were the NHS, affordable transport and housing. Policy announcements made in the run up to the next election must make it clear that Labour understands the rural communities it seeks to serve.

But this isn’t a matter of policy alone. Labour must be comfortable using the language of rural communities and aligning itself with the countryside. This doesn’t mean saying different things to different places. Rather than changing a message crafted in big cities to appeal to rural voters, Labour should root its national campaign in the things that rural areas value: a strong community; pride of place; the beauty of the countryside; a good family life; high levels of security; and a slower pace of life. Such an appeal would not turn off Labour’s base, but could unite the party’s coalition, win back the voters Labour lost, and make it clear to rural areas that the party shares their values.

And by showing it has affection for the whole country, not just parts of it, Labour can persuade the nation it can be trusted to govern – and secure a mandate for the change Britain needs.

This piece was originally published by Renewal.

Image credit: Matthew Waring via Unsplash