Work in progress

Labour has a bold story to tell on workers' rights, writes James Coldwell

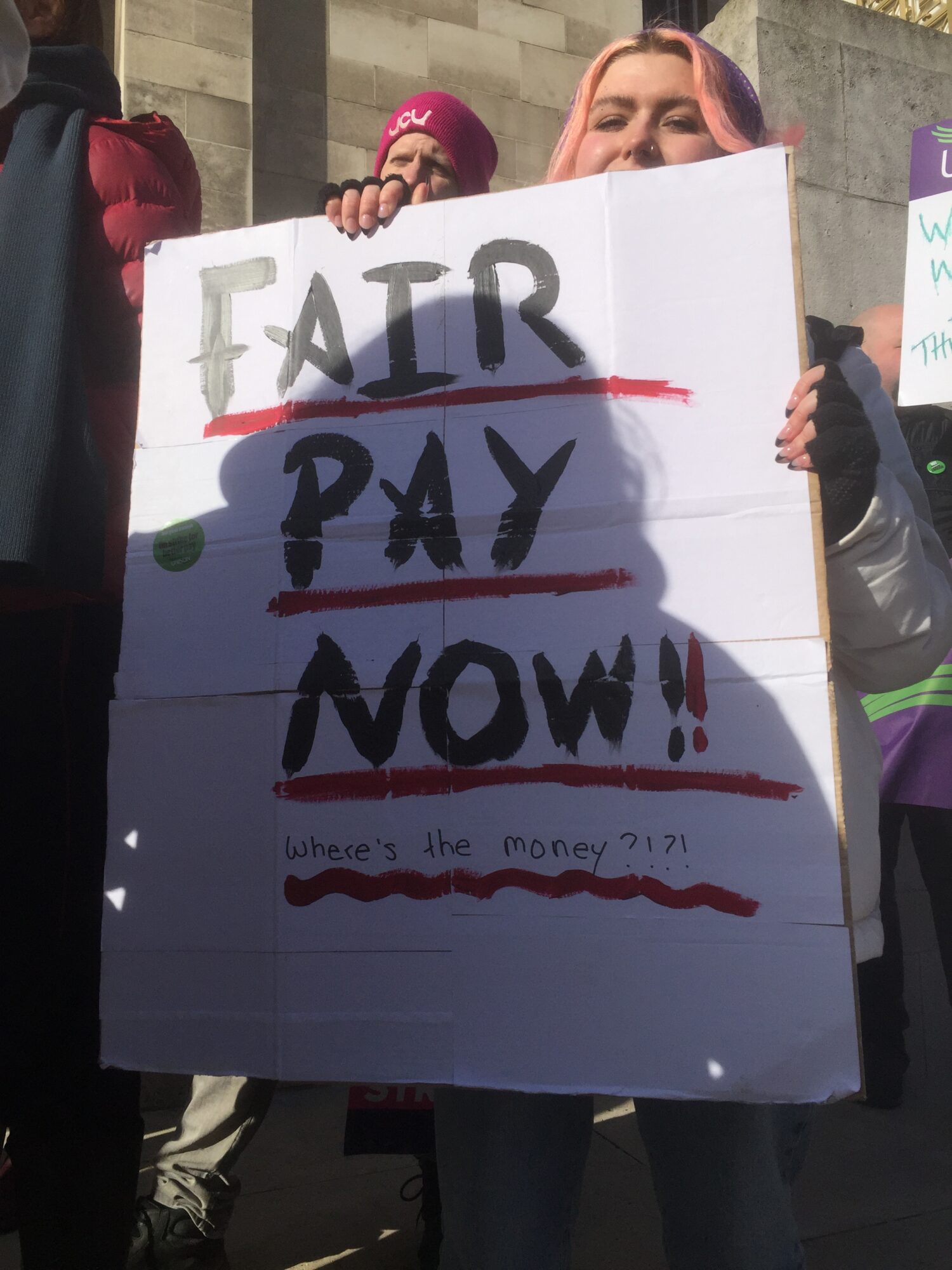

A recent BBC documentary, Strike: Inside the Unions, followed three trade union leaders as they navigated a winter of industrial action. It is a fitting subject for a primetime documentary: 2022 saw the most widespread strike action in the UK since the 1980s.

The most uplifting moment in Strike came as action by Unite bus drivers helped to secure an 18 per cent pay rise for workers. It is one of several cases where unions have won major victories following strikes. Among the more high profile cases, the CWU secured a £3,000 pay rise for BT and Openreach workers – double the original offer – while at the Port of Felixstowe, workers won a 15.5 per cent pay increase over two years.

Unions are right to celebrate successful, hard-fought campaigns. But for millions, wages have fallen way behind the cost of living – and far too many workers lack the agency to improve their situation. It will fall to the Labour party to change this dynamic. As a general election looms into view and Labour’s policy prospectus comes under greater scrutiny, the party has a positive – and bold – story to tell on workers’ rights.

Most obviously, Labour has committed to repealing the government’s proposed anti-strike legislation, with Keir Starmer stating that he will work to “fight and repeal” the bill. Proposals which have to date received less attention are no less ambiguous in seeking to grant greater power to people in the workplace. A future Labour government will introduce a single legal definition of worker, granting rights such as sick pay and protection against unfair dismissal, and removing the qualifying period often imposed before such rights apply.

Flexible working will be expanded, and maternity and paternity benefits will be extended. The latter policy may prove particularly popular given the huge costs of childcare faced by parents and carers, and the growing salience of childcare as an electoral issue. Most recently, Angela Rayner, as Labour’s shadow secretary of state for the future of work, announced that Labour would follow other countries in introducing a “right to switch off”, a pushback against a growing tendency for many employees to earlier this month was anchored around themes of dignity, security and empowerment – a decisive move away from a more narrow on cash transfers that Labour has often espoused in recent years.

Proposals on jobs within specific economic sectors are equally encouraging. Last week the Fabian Society launched its roadmap for a National Care Service, supported by Unison. Better pay and greater union access to workplaces are central to the report, suggesting a serious commitment to ending the recruitment and retention crisis in the sector.

Within the NHS, Labour has combined a desire to create decent jobs with another central plank of its electoral offer: fiscal responsibility. The party has set out in specific terms what its expansionary plans will mean and how they will be funded: 5,000 new health visitors and 10,000 more nursing and midwifery places per year, paid for by reintroducing the 45p tax rate for people earning above £150,000.

Shadow chancellor Rachel Reeves recently announced the party’s commitment to invest £28bn per year in greening the UK economy would be phased in over the course of a parliament. This has been welcomed by some as a sign of Labour’s fiscal credibility, whilst attracting criticism from some environmental groups. But arguably it is in this area where much more detailed thinking on jobs and work is needed. To date, references to the creation of ‘green jobs’ have sounded more hopeful than definitive. Ben Harrison of the Work Foundation has urged Labour to draw up more detailed plans, involving business, local government and trade bodies to ensure the optimistic rhetoric is translated into “secure, long-term green job opportunities.” To persuade some of the sceptics, Labour should aim, as far as is possible, to provide detail on where in the country such jobs will be available, and ensure the right training is available to ensure skills shortages do not act as a brake on the country’s net zero ambitions. As Gary Smith, GMB general secretary, put it: “We need to stop talking about just transitions and start talking about job transitions.”

Nonetheless, Labour’s intent to give people greater dignity and more power in the workplace is clear. As with other policy areas – housebuilding, climate change, social care – the party has moved beyond criticising government failures on jobs and work, and has developed a distinct, bold offer. At GMB Congress, Starmer addressed delegates from behind a lectern displaying the union’s campaigning mantra: “make work better.” It seems increasingly clear that a Starmer-led Labour government will do just that.

Photo: Alarichall via Wikimedia Commons