Pathway to Peace

Those planning for a united Ireland should revisit federalism, argues Dr Brian Caul

After 30 years of bitter conflict and 3,600 deaths, multi-party negotiations reached an agreement in 1998 which raised hopes of permanent peace in Northern Ireland.

Strand 1 of the agreement created an inclusive Assembly with executive and legislative authority. A north/south ministerial council was established as Strand 2 to consider matters of mutual interest within their competence. The east/west relationships were dealt with in Strand 3, in the form of a British-Irish Council (BIC), including representatives from the governments of the Republic of Ireland and Britain, along with representatives from all devolved institutions in the United Kingdom. Meeting twice per year, the BIC was to consider cross-sectoral matters.

The British and Irish governments recognised the legitimacy of the wishes of the majority of the people of Northern Ireland with regard to its status. Reciprocally, the Republic’s government amended its constitution to the effect that a united Ireland would only be brought about by peaceful means with the consent of the majority of the people, democratically expressed, in both jurisdictions in the island. Referenda in both jurisdictions strongly supported the changes and the Northern Ireland Act 1998 ratified the agreement, now commonly known as the Good Friday Agreement.

Over the following 25 years, while violent conflict has largely diminished, the devolved power-sharing Assembly has had a very disrupted and unstable existence, with intermittent periods of direct rule from Westminster. Currently, once again, the Assembly is in disarray and unable to convene due to continuing problems linked to Brexit.

In this context, and especially in light of demographic shifts in Northern Ireland, it is unsurprising that talk of reunification is becoming more and more common. Less discussed are the details. What form could a united Ireland take? What would the constitution and governance structure have to look like to win the support of at least some unionists, and safeguard the rights of all communities on the island of Ireland?

The island today

Both the Republic and Northern Ireland have experienced huge change since 1998. In particular, there are positive indications that communities in both countries are becoming more diverse and culturally enriched by newcomers.

The population of Northern Ireland was recorded as 1,903,100 in the 2021 census, an increase of 92,312 or 5.1 per cent since the previous 2011 census. 3.4 per cent of the population, or 65,600 people, belonged to minority ethnic groups. This is around double the 2011 figure (1.8 per cent or 32,400 people) and four times the 2001 figure (0.8 per cent or 14,300 people).

There is, furthermore, significantly increased diversity from 2011 to 2021 in the population across statistics relating to ethnic group, main language, country of birth and passports held. This increasing diversity is evident across all eleven local government districts in Northern Ireland. Overall, the largest minority ethnic groups in the census were mixed ethnicities (14,400), Black (11,000), Indian (9,900), Chinese (9,500), and Filipino (4,500); Irish Traveller, Arab, Pakistani and Roma ethnicities also each constituted 1,500 people or more.

Official figures recorded the population of the Republic of Ireland in April 2023 as 5,281,600, up from 5,184,000 in 2022. Most of the growth came from net migration, with the rest due to 20,000 more births than deaths. Immigration was at its highest level since 2007, which mainly reflects the impact of Russia invading Ukraine. According to the Central Statistics Office, the number of people immigrating to the Republic in the year to April 2023 was around 141,600, while the number of emigrants over the same period was estimated at 64,000. As a result, net migration was 77,600 – up from 51,700 the previous year. Of those 141,600 immigrants, almost 42,000 were from Ukraine. The others were 29,600 returning Irish citizens, 26,100 other EU citizens, 4,800 UK citizens, and about 39,000 from the rest of the world. Just over 14 per cent of the population, or 757,000 people, were non-Irish citizens.

Not all changes have been positive. There are concerns in both the North and the Republic about the extent of racial hate crimes or incidents. In the North, figures suggest that such crimes or incidents are now reaching the same level as those motivated by sectarianism. Both parts of Ireland have developed institutions to deal with this problem. The Irish Human Rights and Equality Commission (IHREC) is the Republic of Ireland’s national human rights and equality institution, a self-proclaimed independent body that accounts directly to the Oireachtas, the Irish parliament. Its purpose is to promote and protect human rights in Ireland and build a culture of respect for human rights, equality and intercultural understanding in the state. It tries to effect change through legal means, policy and legislative advice, awareness and education, and partnerships across civil society. Its founding legislation with enabled powers is The Irish Human Rights and Equality Commission Act 2014. This Act includes and enhances the functions of the former Irish Human Rights Commission and the former Equality Authority.

The parallel with Northern Ireland is quite striking. Established by the Northern Ireland Act 1998, the Equality Commission for Northern Ireland is also a non-departmental public body its “sponsor” department is the Executive Office. Its powers are derived from statutes over several decades relating to protection against discrimination on the grounds of age, disability, race, race, religious or other similar philosophical belief/political opinion, sex, sexual orientation.

In addition, it has the same responsibilities as all public bodies under the Northern Ireland Act 1998 in relation to statutory equality and good relations duties. Similar to IRHEC, its main actions include advice and awareness-raising; legal representation; and directly taking legal action for court consideration.

It is reasonable to conclude, therefore, that both Republic and the North have developed impartial infrastructures which not only confront but try to prevent discrimination. These impartial institutions could prove particularly useful in a united Ireland.

The unification debate

In 1990, O’Malley pointed to the rapidly changing map of Europe with borders opening and regimes collapsing. He cited Poland, Hungary, Bulgaria, East Germany, Czechoslovakia and Romania as dynamic examples. He maintained that these changes were accelerating the drive towards economic and social integration in the European Community. Herein was palpable evidence, in his view, of people power with the desire to transform societies, to tear down old structures of repression and replace them with governance that would ensure justice and liberty. At the same time, perestroika in the USSR had shown how achievement of new freedoms would sit alongside old problems rooted in the patchwork of ethnic groups. Notwithstanding, he wondered if this might be an impetus for change on the island of Ireland.

As already indicated, the Good Friday Agreement affirmed in 1998 that unification could only take place with majority support in referenda held in both the North and the Republic. And so the debate continued.

In his forthright reflections in 2007, Kenneth Bloomfield, former Head of the Northern Ireland Civil Service and government adviser, emphasised that the creation of the six northern counties by the 1920 Government of Ireland Act was never intended to be permanent and irrevocable. The Act included provisions for a Council of Ireland and later a Parliament for the whole of Ireland (which were never enacted). As he put it: “If the 1920 Act was pragmatically partitionist, it was aspirationally unitary.”

Some social policy theorists have tended to focus primarily on the merits and demerits of devolved governance in Northern Ireland within the United Kingdom. Yet, during the last two decades, the momentum has veered irreversibly towards the disintegration of the UK union. Scotland will eventually hold another referendum on independence and the deep schisms are already all too evident. Furthermore, the aftermath of Brexit has confounded and disturbed many moderate unionists socially, culturally and economically, who, perhaps for the first time, are prepared to consider Irish unification. The emotive unionist election poster slogan ‘This We Will Maintain’, usually situated under a union jack flag, no longer holds sway.

In 2022, ARINS, a project initiated by the Royal Irish Academy and the University of Notre Dame in conjunction with the Irish Times, carried out a poll which revealed that 50 per cent of northern unionists might consider unification if a health services provision akin to the National Health Service of the UK (NHS) was introduced. Reciprocally, 45 per cent of non-nationalist participants indicated they would be less in favour of unification if the health model of the Republic of Ireland was the choice.

Despite long-held unionist beliefs in the North about the costliness of health care south of the border, everyone ordinarily resident in the Republic of Ireland is entitled to a range of public health services either free of charge or at reduced cost.

This has been a historical shibboleth among unionists practically since the foundation of the NHS in 1948 – namely, that it would be a fate worse than death to be launched involuntarily into the perceived weaker health service in the Republic. Yet recent statistics in a report from the Department of Health for Northern Ireland, discussed in a telling article by Freya McClements in the Irish Times, show a health crisis in the North with services struggling due to budgetary constraints and the absence of a Minister of Health. McClements confirms that about 281,000 people per million are on a waiting list for inpatient and outpatient appointments in the North compared with 138,000 per million in the Republic. The picture is even more concerning when the waiting list for more than 12 months is revealed. There are presently 140,000 people per million on this list in Northern Ireland, which is four times as many as those in the Republic, 30,000 per million.

Notably, Northern Ireland currently has the worst health services record compared with both the UK as a whole and the Republic. This points to the vital importance of an open and accurate exchange of information, and the demythologising of assumptions based on groundless fears. For instance, one of the foundation stones of the NHS is that all its health services are free at the point of access. Despite long-held unionist beliefs in the North about the costliness of health care south of the border, everyone ordinarily resident in the Republic of Ireland is entitled to a range of public health services either free of charge or at reduced cost.

When basic living standards are considered, both the North and the Republic have worrying levels of poverty. A Report from the Department of Communities in the North, published on 30th March 2023, revealed that, during the year 2021-2022, 249,000 people (13 per cent of the population) were living in absolute poverty. Similarly starkly, Social Justice Ireland reported that, in 2022, 13.1 per cent of the population in the Republic were living in poverty, defined as having incomes 60 per cent or lower than the median incomes of the country. These findings raise significant questions about persistent inequality and lack of sufficient social security throughout the whole island. They also suggest that fair redistribution of resources throughout the regions must be high on the political agenda after federal unification.

The case for federalism

In 1971, Sinn Féin published Éire Nua – a New Ireland – as a platform for its social and economic policies. Although its active lifespan appears to have been limited, up to the 1980s, its aspirations for a Federal Irish Democratic Socialist Republic are noteworthy (and apparently were given some credibility by loyalist representatives). While it distanced itself from the EU as another form of inflicted colonialism, and adopted a somewhat traditional stance in relation to the preservation of Irish culture, its outline of future governance of the island was thoughtful and progressive. In order to realise its democratic values of decentralisation and involvement of all people in decision-making, a federal model was exhorted which consisted of: the Dáil Éireann (the national parliament) with a suggested location in Athlone as the geographical “centre” of the island; provincial parliaments or assemblies in each of the four provinces elected by proportional representation; and, at local level, regional boards, district councils and voluntary community councils. The duties of each of these bodies were well defined and logically interrelated, underpinned by a proposed Constitution and Charter of Rights. However reactions were mixed, both within the party and externally. Some republicans saw the power devolved to Ulster as an inducement to unionists who, even with the addition of the Republic’s three Ulster counties (Donegal, Cavan and Monaghan) would still have had an inbuilt majority. At times, the plan was expressed in strong polemical style, and this may have stifled wider debate in the North. Later, Sinn Féin distanced itself from armed struggle and took an active part in the consultations which led to the Good Friday Agreement in 1998, including consent to the removal of the territorial claim over the six counties in the North in the Republic’s constitution. This opened the political pathway for Sinn Féin to participate in the new power-sharing Assembly.

Federalism elsewhere

Of all the federal States in the EU, Belgium is perhaps the best model for comparison. It has a population of 11.8 million; the island of Ireland has 7.1 million. Its surface area is 30,452 square kilometres compared with just over 77,200 in the Republic of Ireland. There are three official languages – Dutch/Flemish, French and German. The majority of people, about 58 per cent, are Catholic, 7 per cent other Christian, 20 per cent with no religion stated or atheist, an increasing Muslim minority of about 6.8 per cent and a wide variety of other ethnic minority religions including Judaism, Buddhism, Hinduism Sikhism and Jainism. Even though it is a small country, it decided to adopt federalism, which evolved through several reforms from 1970 to 1993, because of its diverse population and multiple spoken languages. It has been viewed as relatively effective government and power-sharing is regarded as a key factor.

The federal government of Belgium exercises executive power. As a constitutional monarchy, the King is head of state and the prime minister is the head of government in a multi-party system. Decision-making powers are not centralised but divided between three levels of government: the federal government; the three ‘language communities’; and the Regions of Flanders, Brussels Capital and Wallonia. Legally they are all equal and the constitution ensures that no single community can make unilateral decisions. As an evident device to avoid friction, the community governments are elected by the people from each language community irrespective of where they live and this level of government has powers regarding cultural, education and language-related issues. Of additional note is that the regional governments are not subordinate to the central government.

Of special significance in assessing the relevance of the federal government of Belgium to Ireland’s collective future is the evidence that this form of federal government is better than a unitary state because it exercises power-sharing, promotes diversity, empowers regional development and, at the same time, has checks and balances to ensure equal distribution of resources. In my view, this is a vital consideration as the unintentional centralisation of power in an all-island unification could cause in effect the replacement of historical colonial ascendancy with another imbalance of power and resources of our own making.

Why federalism?

Of crucial importance is that any new political infrastructure is appropriate to the evolving history of the island of Ireland.

Straighforward unification would mean the creation of a sovereign state with centralised power, setting up numerous problems in its wake. Policy and legislation would be created by a central body which inevitably would be dominated by certain parties not necessarily representative of the interests of the majority of people in the regions around the island. This would likely exacerbate, and not resolve, the tensions between parties – whether it be the echoes of the 1920s civil war upheaval in the Republic or the sectarian distrust between nationalists and unionists in the North. Exercise of centralist authority and the expectation that regions would comply without any real influence on the formulation of new policies and laws would lead inexorably to embattled and unstable governance.

Relatedly, recent well-meaning attempts to create a model of unification involving a continuation of power-sharing within the six counties is a recipe for early disaster. It reflects the inbuilt contradictions of the 1920 Government of Ireland Act that failed so miserably. This would be tantamount to a placatory pretence, continued partition with the illusion of unification.

As discussed earlier, the whole island of Ireland has experienced enriching cultural diversity in the last decade with steadily increasing numbers of immigrants from minority ethnic groups. For the sake of the future health of Irish society, the means must be made available for active participation in citizenship across local and national levels. This requires nuanced governance which bald total unification does not offer. Instead of having their lifestyles dictated by a remote central government, all citizens must believe that their ideas and needs expressed in local social and political fora, can have a tangible influence and help to shape a fair and egalitarian society.

A fully devolved federal government, reaching out into the heartlands, would be highly geared from the start to foster greater equality among its people

In contrast, there are natural and acceptable ways in which federal authority can be devolved in depth among the four historic provinces, right through to their grass roots at local level. The strengths of such federal government are manifold. Having regional parliaments and local councils which are democratically elected should actively engage all citizens and remove any question of geographical isolation. All of the organs of government would have equal status and all ideas for positive change would be valued. It is vital that all the people of Ireland, regardless of age, sexuality, disability or ethnic background, feel that they have democratic ownership of the new structures and are encouraged to develop their citizenship skills in order to participate and persuade at all levels. The health of a society can be determined by the way it treats its most vulnerable citizens and newcomers, and the federal structures outlined below provide a direct mandate to officers and elected representatives to reach out, listen to and engage their constituents.

The extent of poverty levels remains a serious concern, as does the limited access to further and higher education among young people from relatively disadvantaged backgrounds. It is questionable whether governance within a straightforward unification model would be sufficiently equipped to assess accurately the extent of these issues and bring about the radical changes that they demand. In clear contrast, whether it be in relation to living expenses, housing, work or fair access to third level education, a fully devolved federal government, reaching out into the heartlands, would not only be able to tackle its international obligations as a new federal member state of the European Union, but would be highly geared from the start to foster greater equality among its people and to undertake the distribution of resources needed to provide everyone with a decent quality of life and opportunity for personal and community development.

Checks and balances will be essential to prevent usurpation of power by authoritarian groups or parties. An interlocking federal system would provide these safeguards. For instance, each of the four provinces would elect members to the federal parliament on an entirely equal basis. The president, as well as being elected by a national vote, would be answerable to congress and the upper chamber for any use of his decision-making powers. These are discussed below, along with the essential content of the constitution and the Bill of Rights.

A federal constitution

There have of course been challenges and tensions within existing European federal states. However their strengths in striving for pluralist and peaceful co-existence, especially in Belgium, should offer real encouragement. It is, however, imperative that, in detailed and open consultation, both parts of Ireland develop a model which is mutually beneficial and which in due course wins the approval of the vast majority of citizens throughout the island. It is hoped that the model presented below can be a starting point.

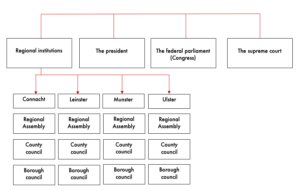

The most effective form of federal government will be one which allows a wealth of decision-making and accrual of income at the most localised level possible. Thus the central apex of power, in the form of the president and the federal parliament, literally serve the localities while making them accountable for their autonomous decisions and actions. The overall structure of government should consist of the following components.

The president should be elected by a national vote on the basis of proportional representation. All political parties would have the right to nominate candidates, ensuring that all areas of the island would have a voice in electing the first citizen. The president would have an executive role including the power to veto legislation, approved by congress and the upper chamber, but would be answerable to both Houses for such decisions. In the case of deadlock when constitutional issues arise, they could be referred to the Supreme Court for resolution. Furthermore, all functions at the top of government would be subject to the separation of powers which delineates functions into legislative, executive and judicial powers – a comprehensive protection in law against any administrative autocratic decisions.

Regional assemblies would assume public responsibilities with appropriate powers. Similarly, the local authorities in the form of county councils and borough councils would have certain autonomous rights and implement assigned public responsibilities on the basis of state directives and delegation of administrative tasks.

Each of the four provinces would have the right to elect members to the federal parliament on an entirely equal basis. In a parliamentary congress of 100 members, each province would elect 25, using proportional representation to ensure that minority groupings have a fair opportunity to have their voices heard, helping to eradicate any semblance of the historic majority dominance in the North. Likewise it creates the opportunity to end once and for all the party schisms, dating back to the civil war, that have warped political thinking in the Republic since the 1920s. In parallel, the restoration of historic Ulster would be palatable to the vast majority of those living in the North. Of course there will be transitional costs to ensure the equal maintenance of quality of life, but the resources will undoubtedly be found through the combined goodwill of the British and Irish governments and the European Union.

A delicate but necessary step will be the creation of a new constitution which reflects the increasing pluralism and diversity throughout the island, and underlines emphatically the importance of the total separation of church and state. It will also mirror the values of the newly created Bill of Rights which will be an essential reassuring pillar for all citizens.

A bill of rights

An essential cornerstone of the transition to a federal Ireland must be a Bill of Rights to allay the fears of people right across the island. Its cardinal principle must be that the ultimate value which governs our new society is the recognition of all citizens as persons of worth with an inalienable right to dignity and self-respect. A prerequisite of a true democratic society is the manner in which it treats its most vulnerable and least powerful members. In the foregoing account, evidence has been shared of the glaring and rampant inequality in so many spheres of Irish life, north and south. The introduction of a Bill of Rights will be a directive to every individual, representative or organisation in society to protect and promote its principles.

A fundamental article in the Bill must be the affirmation that men and women are born free and equal in respect of their rights. These rights will also be extended, not only to citizens, but to newcomers regardless of race, colour, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national and social origin, property, birth or other status. If historical forms of oppression are not to be simply replaced by other forms, the new federal society has to be open to and permeable by cross-cultural influences.

Another key tenet is that everyone has a fundamental right to life, liberty and security of their person. The inerasable evidence of killing, self-destruction and enforced loss of liberty in Northern Ireland since 1968 is a testimony to the essential importance of these principles.

Just as no person should have the power outside a legitimate court of law to take the life on anyone into their hands, so the Bill of Rights has to affirm that no-one should be harassed by officialdom on account of their beliefs or opinions, if their expression does not endanger the public order.

Unequivocally, the new federal society must set its face against any emergence of future paramilitary activity and the Bill of Rights must proscribe any individual, group or association other than that which is derived from the laws of the state. Reciprocally the law must be the expression of the will of the whole community, who should be afforded the opportunity to participate in its formation, either personally or through representatives. An emphasis in the Bill of Rights should be placed on the importance of all citizens having both rights and obligations to each other.

Imperative to formation of a truly egalitarian society is the right of every citizen to free education. This should include access to further and higher education. In both parts of the island, the gap between aspiration and reality is all too clear. Development of self through education in a pathway that suits strengths and interests should be a universal right, not just the realm of people who are better off.

Equally, it is vital that the Bill of Rights acknowledges and underlines the rights of citizens with physical disabilities or mental health challenges. They too have a right to full participation in society and access to support services suitable for their needs.

Of significance too in a changing world, the Bill of Rights should address the right to access to facilities for rest and leisure, and in parallel require limits to working hours in order to enable citizens to benefit from these facilities. If everyone is actively encouraged to participate fully in cultural life, the reward will be a deeper sense of mutual understanding and respect.

It is essential that the principle of change by consent is enshrined in the Bill of Rights. It should be made crystal clear that the citizens across the island of Ireland do have a right to self-determination. I recommend that the special Commission considering the process and outcomes of a federal Ireland in advance of a referendum should also be responsible for the drafting of this Bill of Rights, as vital information for the voting public about the potential scope of the social and political changes ahead, and reassurance about their rights during and beyond this process.

This model for a federal Ireland is offered in the spirit of trying to open up a proper and substantial debate on the future of the island of Ireland and all its people. Political leadership is now needed to champion these ideas and pave the way for an All-Ireland Constitutional Commission which will transform them into positive and practical reality, and seek the consent of all our people through simultaneous referenda. The vast majority of our people desire peaceful and mutually respectful co-existence, and hard-earned prosperity. Our emergence as a new federal member-state of the European Union will achieve those goals.