On the Fence

The large number of undecided voters means Labour can't take anything for granted, writes James Prentice

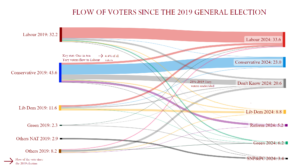

Fig 1 – Flow of the vote since the 2019 election according to the British Election Study (BES) – Wave 25 – conducted May 2023

In the second half of 2022, the Conservatives imploded. First, a chaotic summer exposed Boris Johnson’s lies and ineptitude and culminated in his resignation. Then, Liz Truss created such economic devastation with her failed mini-budget that she was forced to resign after just 49 days. These events enabled Labour to forge a 20-point lead in the polls, and despite Sunak and Hunt being brought in to steady the ship, Labour has more or less maintained this gap since.

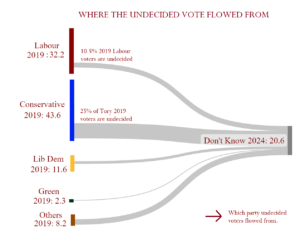

The headline figures neglect to mention, however, that this lead only reflects the intentions of 80 per cent of the electorate as 20 per cent of voters remain undecided (see figure 2).

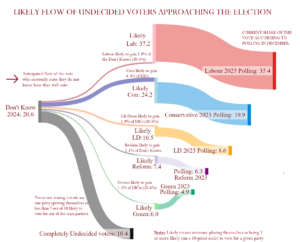

When taking into account undecided voters, Labour currently has 35.4 per cent of the electorates’ support, the Conservatives have 19.9 per cent, the Lib-Dems 8.6, Reform 6.3 and the Greens 4.9. According to Electoral Calculus (a seat projection website), this would give Labour a 232-seat majority. Labour supporters might be forgiven, then, for thinking that even when taking undecided voters into account, the next election is in the bag. However, if these voters decided to back the Conservative party in large numbers, the polls would narrow sharply. Indeed, my analysis of the British Election Study (BES) shows that when taking undecided voters into account, Labour’s lead can fall to 11 points, something which would substantially reduce Labour’s anticipated majority, possibly even causing a hung parliament.

Fig 2 – Where undecided voters have originated from according to the British Election Study (BES) – Wave 25 – conducted May 2023

Therefore, understanding who these voters supported in the last election and where they are likely to go is key to knowing the extent to which the polls can narrow during the short campaign. This is especially important in the key marginal constituencies, which tend to contain more non-partisan voters who often stay undecided until polling day.

Where will undecided voters go?

Undecided voters that will likely support the Conservatives:

Just under 11 per cent of the electorate are undecided voters who backed the Conservatives in the last election. This represents a full 25 per cent of 2019 Conservative voters (see figures 1 and 2). Thirty-four per cent of this group, 3.6 per cent of the electorate, state they are likely to vote for the Conservative party in 2024 (likely is defined as someone placing themselves as 7 or above to vote for a party on a 10-point probability scale). A further 0.1 per cent of the electorate are undecided voters who voted Labour in 2019 but now report they are likely to vote Tory. Additionally, 16 per cent of 2019 Lib Dem supporters who are currently undecided indicate a strong likelihood to back the Tories in the 2024 election, increasing likely Conservative support by a further 0.3 points. As shown in figure 3, this means that once the election approaches and all these undecided voting groups are forced to choose their next government, the Tories could well secure an additional 4.3 per cent of the electorate.

Fig 3 – This Sankey Diagram shows that flows from individuals currently undecided (who are likely to vote for one party over other choices available) could give the Conservatives a 2.5 point net gain over Labour

Undecided voters that will likely support the Labour party:

A smaller group, 3.4 per cent of the electorate, are undecided voters who supported Labour in 2019 (see figures 1 and 2). This represents 10.5 per cent of all people who voted Labour in 2019. A quarter of these voters say that they are likely to support Labour again in the next election, meaning Labour’s share of the vote will likely increase by another 0.9 points.

Labour is also likely to receive support from 6 per cent of undecided voters who supported the Conservative party in 2019, equating to 0.6 per cent of the electorate. Moreover, according to the BES, Labour is likely to gain 16 per cent of undecided voters who backed the Lib Dems in 2019, yielding an additional 0.3 increase in support. As shown in figure 3, once all these undecided voting groups go to the polls, the Labour party is likely to secure a further 1.8 per cent of the vote.

How much will this cause the polls to narrow?

The relatively large number of undecided voters likely to vote Conservative means Labour’s lead is likely to narrow by at least 2.5 points once the general election arrives and undecided voters are forced to make a decision.

This may sound like Labour would still have a comfortable lead, but when adding together undecided voters likely to back the Lib Dems, Reform and the Greens, the BES finds only half of undecided voters have already indicated they are likely to support one party over the other available options. Crucially, this means that just over 10 per cent of the electorate are completely undecided, meaning they do not respond as saying they are likely to vote for any given party. If the Conservative party can win over these undecided voters, then Labour’s lead would dwindle. This could leave Labour vulnerable in key marginal seats and make the election tighter than many anticipate. Therefore, whilst BES data shows Labour to be ahead in these key marginal seats, because of the large numbers of undecided voters it should not be assumed these seats are easy wins for Labour.

How many completely undecided voters can the Tories realistically win?

Although 10 per cent of the electorate report they are completely unsure who they will vote for, it is important to note that the Conservative party will not win all of them over.

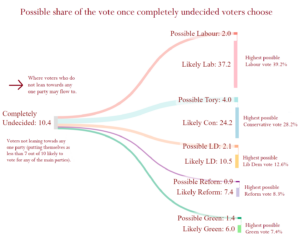

Fig 4 – How completely undecided voters may influence the polls according to the British Election Study (BES) – Wave 25 – conducted May 2023.

Of the ‘completely undecided’ voters, a full 6 per cent of the electorate report that they are unlikely to vote Tory, meaning they report their likelihood to vote Conservative as three or less on a 10-point scale. As such, these ‘completely undecided’ voters are therefore unlikely to contribute a gain larger than 4 points (see figure 4). Nevertheless, taken together with the 2.5 per cent of the electorate who report that they are undecided but leaning Tory, this means the polls could narrow by as much as 6.5 points.

How many more voters can Labour compete for?

Labour is similarly restricted in how many more voters they can win. Twenty-nine per cent of undecided voters who voted Labour in 2019 state a low likelihood of voting Labour in 2024, meaning Labour are unlikely to regain this 1 per cent of the electorate. Further, 56 per cent of undecided voters who backed the Conservatives in 2019 also stated they were very unlikely to support Labour, a group comprising 6 per cent of the entire electorate. Additionally, Labour will find it hard to win over another 0.8 per cent of the electorate, with 49 per cent of former Lib Dem voters who are currently undecided indicating they are unlikely to support Labour in 2024. Therefore, this means that out of the 10 per cent of undecided voters not leaning towards any party just 2 per cent of the electorate are open to voting for Labour (see figure 4).

The impact on Labour’s electoral prospects

When taking into account undecided voters who have indicated that they are likely to support a particular party, Labour secures 37.2 per cent of all voters’ support, the Tories 24.2, the Lib Dems 10.5, Reform 7.4 and the Greens 6 (see figure 3). This would produce a majority of 128 for Labour, according to Electoral Calculus. But once we include the 10 per cent of the electorate who do not lean towards any particular party, if all the individuals open to voting for the Conservative party back them on polling day, and Labour secure no completely undecided voters, this would narrow the polls by a further 4 points. According to Electoral Calculus, this would reduce Labour’s majority to 72.

All this means that if Labour were to lose some of the 4.4 per cent of the electorate they have taken from the Tories, they would be close to a hung parliament result. Depending on how many former Tory voters they lost to the Conservative party, Labour’s majority would range from 72 to just under 50, with some Electoral Calculus projections showing that the worst-case scenario would leave them a few seats short of an overall majority.

Undecided voters, then, should take centre-stage in Labour’s pre-election planning. Labour should compete for all undecided individuals open to voting for them, and ensure that they retain the voters they have secured from the Tories to starve the Conservatives of a voting base large enough to challenge them. Only by achieving these things on polling day can Labour realise its electoral ambitions.

Image credit (pinned News and Insight): Jens Lelie via Unsplash