The Politics of Development

Two years ago, the G20 committed themselves to promoting inclusive and sustainable economic growth, having argued that ‘for prosperity to be sustained it must be shared.’ Yet as world leaders prepare to attend the next G20 Summit in Mexico next...

Two years ago, the G20 committed themselves to promoting inclusive and sustainable economic growth, having argued that ‘for prosperity to be sustained it must be shared.’ Yet as world leaders prepare to attend the next G20 Summit in Mexico next month, new data from Oxfam has shown that inequality has increased in all but four of the G20 countries. Oxfam’s Left behind by the G20? report shows that only South Korea, Brazil, Argentina and Mexico have managed to reduce inequality over the last two decades.

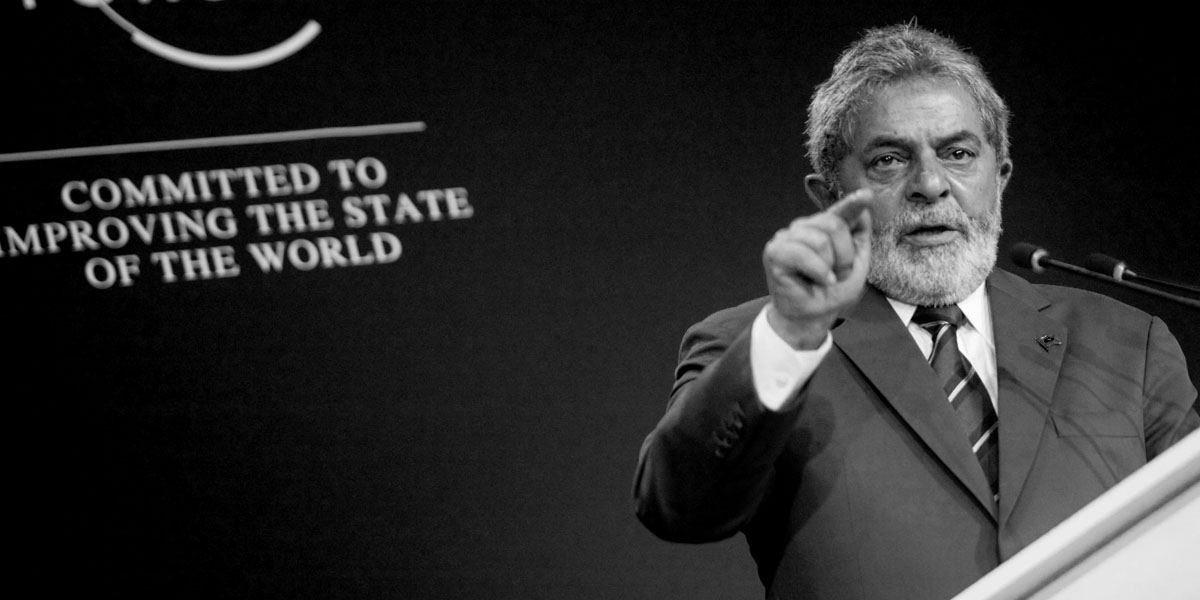

The stand out performer among that group is Brazil. Over the last decade Brazil has managed to marry impressive rates of growth with significant progress in reducing inequality – growth averaged 4.1% whilst the GINI coefficient fell by 4% between 2003 and 2010 – cutting the number of Brazilians’ living in poverty in half. Their progress is even more impressive when considering the nation’s history of high and entrenched inequality.

It is no coincidence that these successes have occurred under a social democratic regime. The flagship programme has been President Lula’s Bolsa Família, which continued under Dilma now reaches 46 million poor families, providing them with financial aid conditional on them ensuring their kids are vaccinated and attend school. It has even helped tackle child labour – illegal but still afflicting 7 million kids – by providing after-school activities to prevent children going to work when the school day ends.

Social democratic-run countries in Latin America have even been more successful at reducing inequality than their more left-wing counterparts, such as Venezuela, according to recent analysis by the US based Centre for Global Development.

Frankly, the policy recommendations of Oxfam’s report – calling for Brazil’s cash transfer programmes to be replicated, for investment to achieve universal health and education, progressive taxation, action to tackle discrimination against women and girls, and ensuring fair distribution of land and resources – read like they were lifted from a Partido dos Trabalhadores’ manifesto.

Brazil’s progress on reducing poverty and inequality didn’t happen by chance. It didn’t happen because of statistics or facts, however compelling. It didn’t happen because of petitions or protests, however weighty or loud. It happened by choice – political decisions taken by progressive politicians in elected office.

And the sad truth is that – as a charity – Oxfam cannot say as much. That is not to ignore the powerful role protest movements can play in bringing about change, from the Arab Spring to the anti-Apartheid and Indian independence movements. But what makes Mandela such an inspiration is not just his courage through those 27 years behind bars – but his leadership in the 5 years he was President – introducing free health care, increasing schooling, and building new houses. And whilst Gandhi is rightly revered the world over, it was Prime Minister Nehru who took the hard and difficult decisions needed to keep a deeply divided nation of millions together and at the same time create jobs, criminalise caste discrimination and introduce universal primary education.

In the UK the Make Poverty History campaign was incredibly successful, and as a former campaigner with Oxfam myself I have always looked up to those who worked on it and felt humbled by their achievements. But if we are honest the true success of that campaign was in creating a (very large) space for politicians to act. If we had not had politicians with the power and the will to act – or in other words if we had not had a Labour government – we would not have achieved the dropping of debt and aid increases that have transformed so many millions of lives. Ultimately, when those deals were being thrashed out in G8 meetings it was not Bono or Geldof who forced world leaders to sign on the dotted line but Blair and Brown.

Increasing inequality is entrenching poverty, rising unemployment is hampering aspirations, damaging climate change is devastating communities. These are global problems requiring global solutions – co-operation, Keynesian economics, progressive taxation, fairer trade, green jobs, universal health and education, social protection.

These are social democratic solutions based on social democratic values. Yet it is left to global civil society to advocate them – and as they will never stand for office they will never have the power to implement them. Which means we – the social democratic left – need to get our act together and fill that vacuum.

Easier said than done, unless of course you believe in the power of wallpaper pasting tables, copies of the Socialist Worker and yelling “Workers of the world unite” until you are (some would say ironically) blue in the face.

The decision of who to support is hard enough – and somewhat messy. There was much to celebrate in January when the ANC reached it’s 100th birthday, but no one should be comfortable with the elitism at the top of the party or demagoguery of its youth wing. The current Indian National Congress government has made education free and introduced programmes to guarantee employment and health in rural areas, but they have seen inequality rise on their watch and found themselves on the wrong side of the argument on corruption. Rwanda has made massive strides under President Kagme’s leadership but it has also seen political rights curtailed – do we believe a strong-man is needed to keep together the country after the genocide or do we withdraw our support? Why an earth did Socialist International allow Muburak’s party to be a member for so long? Who do we support in countries where ethnic division and big personalities matter more than policies or values?

So understanding the politics must be starting point, and I hope the Labour Campaign for International Development (LCID) can begin to do some of that analysis. Beyond that we could look at what we as sister parties can do practically to support each other better. How can we modernise Socialist International and make it fit for purpose? How can we up-scale the great work the International Office of our Party is doing through the Westminster Foundation for Democracy to support sister parties across the developing world? And what can we learn from them and programmes like Bolsa Família as we plot our return to power in the UK? The Young Fabians will run a trip to the US later this year to help Obama be re-elected – why not a trip to help PM Singh’s INC retain control of the Lok Sabha? I hope LCID can organise one in the future.

Of course the first priority for all Labour Party members is to get our Party back in Government. But we should put aside at least some energy to how we can better work together with social democratic parties around the world.

It is in our national interest to do so – because so many of the challenges we face in the UK require global solutions. But it is also an important part of our identity, and one of the reasons Blue Labour’s ‘flag and family’ mantra jarred with so many of our members– for internationalism is in our Party’s DNA.

We want the boy who begs on the streets of Bangalore to have the same start in life as the girl with a Sure Start centre at the end of her road in Brixton. We want the guy who works on the checkout of the Walmart in Wyoming to have the same union rights the bloke at the BMW factory in Berlin. And we want the honourable member for Feltham & Heston to have as many female colleagues as the member for Kigali Central in the Parliament of Rwanda.

‘Left behind by the G20’ is a must-read report. Perhaps ‘Left in power in the G20‘ is the report that needs writing next.