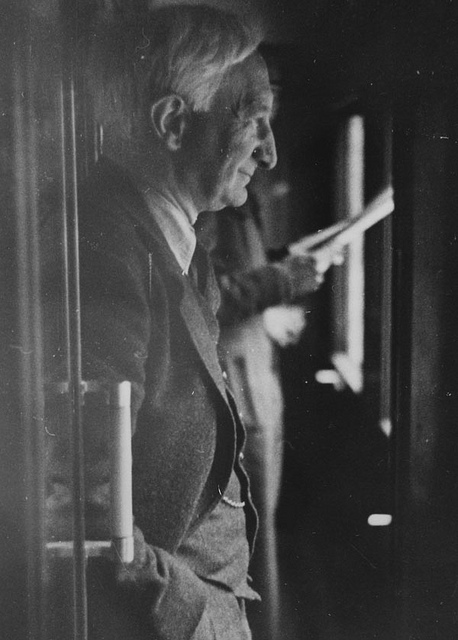

Who was William Beveridge?

70 years ago, at one of the darkest moments of the second world war, an obscure interdepartmental report on Social Insurance and Allied Services, composed by a temporary wartime civil servant, William Beveridge, suddenly shot to fame as what was...

70 years ago, at one of the darkest moments of the second world war, an obscure interdepartmental report on Social Insurance and Allied Services, composed by a temporary wartime civil servant, William Beveridge, suddenly shot to fame as what was at the time the best-selling ‘blue book’ in British history.

The ‘Beveridge plan’, as it was instantly called, set out a comprehensive agenda for the abolition of poverty in Britain, not as a mirage of utopia, but as what its author claimed was “a practicable post-war aim”. Underpinning the plan’s proposals were four main strategies that signalled a major development from previous national policies: the extension of existing, limited social-insurance schemes to provide coverage for all citizens; a comprehensive, free national health service; tax-financed family-allowances for all second and further children; and more tentative (and ultimately more controversial) policies to maintain ‘high and stable employment’, as both a good in itself and to avoid bankrupting the national insurance fund.

As under previous schemes, benefits were to be jointly financed by three-way contributions from workers, employers and the exchequer; but benefit-levels were to be ‘scientifically’ related to subsistence needs, defined by what was adequate for ‘basic healthy living’. Benefits were not, however, to be so generous as to discourage additional voluntary insurance through friendly-societies, trade union benefit schemes, and other forms of mutual aid (which Beveridge saw as essential features of a flourishing civic culture).

Published in November 1942, over 500,000 copies of the report were sold within three days, and Beveridge rapidly became a household name – not just in Britain but in the USA, the British empire, and many parts of occupied Europe. Despite its widespread public acclaim, however, the report provoked much behind-the-scenes consternation among civil servants, entrepreneurs, orthodox economists and coalition ministers of all parties. Some believed its proposals were grossly premature in a war for national survival; others that it would arouse expectations of post-war prosperity that would prove impossible to satisfy; whilst a third group objected on more philosophical grounds that (even if affordable) such policies would be the kiss of death to any hope of return to a competitive market economy.

In the event, public support for the Beveridge plan proved so strong that ministers and Whitehall departments started preparing for post-war reconstruction almost as soon as the report was published. But Beveridge himself was expressly excluded from this process, and even from making contact with officials who were charged with implementing his own social-security proposals. That exclusion may seem, in retrospect, to have been a strange over-reaction to what (beneath its purple passages) was basically a rather dry and technical document. A document which built on policies that had been progressively evolving in British society over the previous half-century, and that was acknowledged even by its critics to be well-costed and economical. But it expressed a feeling (even among some of Beveridge’s admirers) that the razzmatazz generated by the report had gone beyond what was constitutionally proper; while to others it seemed that there was no stopping-place between Beveridge’s well-meaning social reformism and inexorable descent into an authoritarian state. All of this raises the question of who exactly was the William Beveridge who caused this furore? What were his underlying social, economic and political ideas? And why were they seen in certain quarters as so dangerously controversial?

Beveridge had been born in India in 1879, the son of a judge and apparent pillar of British imperial rule, who had, nonetheless, severely damaged his career by his outspoken championship of native Indian causes. The elder Beveridge had also been an ardent disciple of the French positivist philosopher, Auguste Comte, and of his teachings on ‘altruism’, the subordination of private interests to the common good, the basic unity of natural and social science, and a strongly ethical ‘religion of humanity’.

Unlike his father, William Beveridge himself was never a member of the organised positivist movement, but powerful traces of this ‘positivist’ inheritance could nevertheless be detected at many points in his mental outlook and public career. It could be seen, for example, in his belief that ‘society’ and social institutions could be studied by methods borrowed from the natural sciences. And it could be seen also in Beveridge’s lifelong view – by no means shared by all English progressive liberals – that ‘good government’ and forward planning could override the damaging side-effects of market forces. It also helps to explain Beveridge’s surprising admiration for the teachings of John Ruskin (not for Ruskin’s philosophical High Toryism, but for his practical involvement in apprentice schemes, working-class higher education, housing programmes, and emphasis on the ‘dignity’ of public works).

These ideas lay behind Beveridge’s role as a pioneer of labour exchanges and statutory social insurance during the ‘new liberal’ phase of British social policy from 1908-14. And they help also to explain his lifelong association with and admiration for Sidney and Beatrice Webb (even in periods when he deeply disagreed with them over major issues of political theory and high politics).

Such influences suggest that, although Beveridge always identified himself as an ‘advanced liberal’, his policies cannot be squeezed into any single party ideology or tradition. In all these respects, it is perhaps not hard to imagine that Beveridge might have found much common ground with the Blue Labour and Red Tory movements of the present day.

Jose Harris is Emeritus Professor of Modern History at St Catherine’s College, University of Oxford and is author of William Beveridge: A Biography.

(copyright Nov.2012)