Perverse incentives

It is very easy to say that everyone who can work should work. It is also something that most people would agree with, including those who are out of work. However, finding and keeping a job is not always easy,...

It is very easy to say that everyone who can work should work. It is also something that most people would agree with, including those who are out of work. However, finding and keeping a job is not always easy, especially for those who have a chronic illness or disability.

It is not so easy to find employers willing to take on someone with a history of mental illness, someone who has a poor health record, or someone who has just received a diagnosis saying they have cancer or a degenerative disease. Yet many of the people who are ‘failing’ the discredited work capability assessment (WCA) and are being found fully fit for work still have significant health problems.

Much of the coalition government’s rhetoric suggests there are the people who work and the people who don’t work. However, the reality is that most people who are out of work at any one time have been in work for a large part of their working life. For some, it may have been the revolving door of short-term low paid work, followed by periods out of work. If such a person develops a problem with their health and is unable to take on the low paid, physical work available then it becomes very hard for them to find anything else.

The main criticism of incapacity benefit (IB), and invalidity benefit before it, was that many of the people who were long-term unemployed with a health problem were merely shifted on to IB and then forgotten. Unemployment was kept artificially low, while claimants got their money every week and weren’t expected to do anything in return. No signing on, no obligations to prepare or look for work. Labour did try to engage with people on IB, to give those who were interested in getting back to work a helping hand through a variety of incentives and employment support schemes, the most successful of which was pathways to work. This provided support to help people with disabilities to overcome the barriers they faced in re-entering the work place. As a result until the economic downturn in 2008 the numbers on IB were slowly beginning to come down for the first time.

Based on what has been happening over the past year, as those on IB are moved to the new employment support allowance (ESA), figures are likely to show that the numbers on an out of work disability benefit are coming down more rapidly than ever before. This is because around a third of those presently on IB are being found fit for work when they go through their WCA and so are being placed on job seekers allowance (JSA) instead of ESA.

I am fairly sure the coalition government will hail this drop as a huge success, proving that people who were perfectly able to work were languishing on benefits. This is the group who have come in for so much criticism in the tabloid press, being called ‘scroungers’, ‘work-shy’ or ‘on the fiddle’. However, just because people have been moved on to JSA doesn’t mean they have found work. Nor does it mean that people who have come off benefit completely have gone into work either. Some will have found work, but by no means all and it will be some time before we have any figures to know how many.

The coalition government is in danger of creating yet another forgotten generation. This is because, due to the Welfare Reform Act, which passed last year, contributory ESA is stopped after a year for those who have been placed in the work-related activity group (WRAG) of ESA. These are people who are not deemed so ill or disabled never to be expected to work again, but are not well enough to be expected to find a job in the short-term, and who live in a household whose income is above income support levels. Contributory ESA can be stopped even if a personal adviser doesn’t think you are well enough to be referred to one of the work programme providers to undertake work related activity.

With the loss of benefit, there is no incentive for the individual to engage with Jobcentre Plus, especially if they feel they are unlikely to get a job. As they are receiving no benefits, there are no sanctions the jobcentre can impose and there is no incentive for the government to spend money on trying to get them into work.

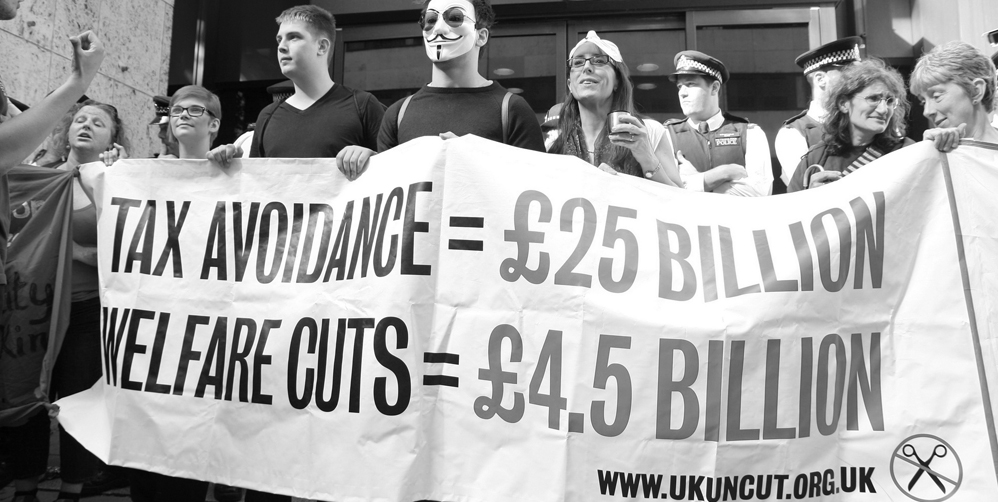

It is sad to think that the people in this group are those who, until their ill health or disability made it difficult for them to find work, worked all their lives, paid their national insurance contributions and either have some savings or a partner who is still in work. They have done everything the government has said is the right thing to do, but at the point when they expect the state to step in to help, that help runs out after either six months (if they are on contributory JSA) or a year. It is little wonder many think the incentives in our welfare system are perverse and seem to punish those who did work and did save – not what Beveridge envisaged at all.