Labour must fill its policy void in 2013

Today over 1,000 delegates gather at the Fabian Society's annual conference to hear Ed Miliband and his frontbench team set out their stall for 2013. The Labour faithful come together at the start of the year in far better spirits...

Today over 1,000 delegates gather at the Fabian Society’s annual conference to hear Ed Miliband and his frontbench team set out their stall for 2013. The Labour faithful come together at the start of the year in far better spirits than 12 months ago, when the two big parties were neck-and-neck in the polls. Since then they have seen the coalition descend into omnishambles, a strong and consistent poll lead for Labour and Ed Miliband’s cunning theft of the “one nation” strapline as an inclusive and reassuring label for his leadership.

Yet at the halfway point of this parliament there remains something hollow in Labour’s resurgence. In electoral terms Labour is in a very strong position, owing to the implosion of the Liberal Democrats, a flatlining economy, the possible rise of Ukip and the slow tarnishing of David Cameron’s personal brand. But the party’s revival feels somehow flimsy, because people struggle to say what Labour stands for and how it would govern if given the chance.

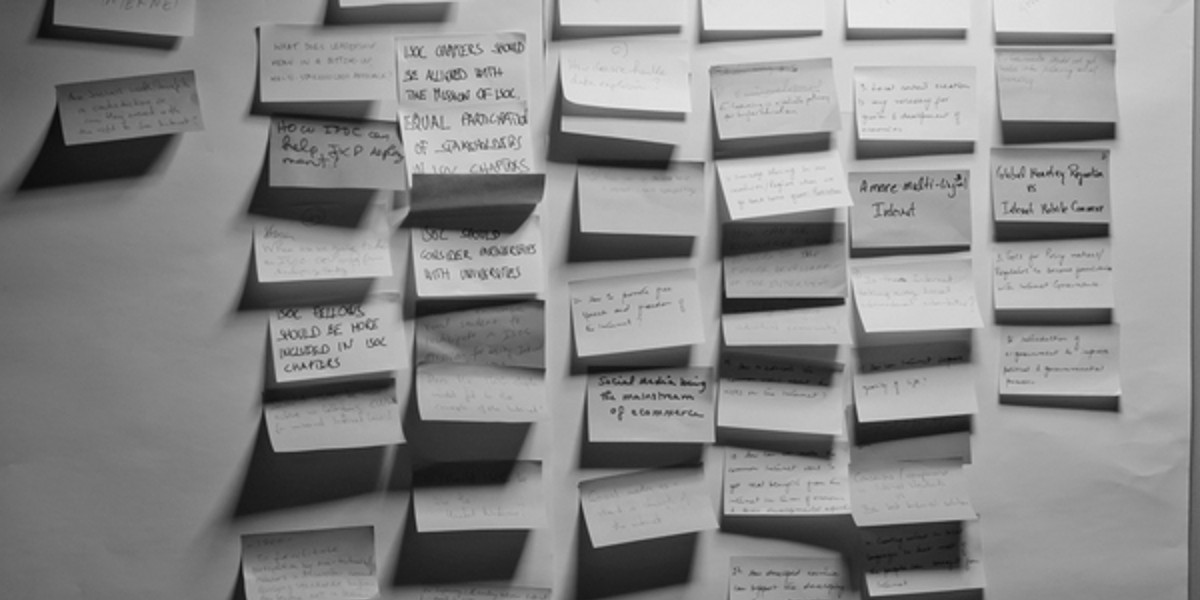

Those of us within Labour circles observe a ferment of competing ideas and buzzwords, and can already point to a slew of new policies. Indeed one senior party insider told me he feared the party’s problem was that it had too much policy, not too little. But to the outsider Labour is a void.

The party may have lots of little policies, however too many are worthy but dull: workers representation on remuneration committees, more consumer regulation of energy markets, new company reporting rules and so on. Now it needs big, emblematic promises that sets it apart from the coalition, capture the spirit of how it will govern, and stand half a chance of breaking into the public consciousness.

Today’s Fabian conference considers the left’s approach to public services and the welfare state. It’s an area Labour figures love to talk about, but where so far it’s hard to say how the party’s plans differ from those of the coalition. Across most of the key public services – schools, the NHS, policing, universities, local government – the party has opposed cuts and market-based reforms but as yet has no alternative story to tell. So what does Labour want to do with these vital services, given it will have no extra money to patch up the worsening provision it will inherit?

Will it broadly accept the landscape it is bequeathed, complete with service fragmentation and rationing, private outsourcing on a huge scale, a whiff of 1950s nostalgia and growing inequalities in accessing services? If not, flagship policies are needed to prove to the public that “one-nation” Labour has a clear alternative to the combination of marketisation and bossy statism that the coalition has inherited from New Labour. For example, can the party sign up to the mutualisation of private sector workfare, criminal justice and railway services? Will Labour dare to replace the fragmentation and slow-motion privatisation of schools and healthcare with local democratic co-ordination and leadership?

Nearer the election the party will need to set out a rival plan for the public finances to show how it is possible to achieve deficit reduction without further cuts on a grand scale. That can wait until the economic picture is clearer, but in the meantime Labour needs to decide what new spending promises it can afford to make soon. There are powerful political and economic arguments for commitments on house-building, social care, contribution-based welfare entitlements, childcare, and Ed Balls’ new pledge of guaranteed jobs for the long-term unemployed.

Any of these could be big enough ideas to appear on a 1997-style pledge card, but they need to be carefully costed and then linked to a politically acceptable source of revenue. This might mean targeted tax rises, alternative spending cuts or market interventions that save government money, such as a higher minimum wage or rent controls. Labour needs to hold out the hope of a better welfare state, not just managed decline, but its plans must never seem to put sound public finances at risk.

This is not work that can wait. It takes months to properly stress-test new ideas, particularly with the meagre resources opposition parties have at their disposal. But after that it takes years before people begin to notice what an opposition is saying so the key policy pledges of Labour’s alternative will need to be repeated incessantly for 18 months. Even then most people will only be starting to notice.

The costs of inaction are high. Without a clear and challenging policy programme, Labour may well limp to a default victory, as this government seems hellbent on self-destruction. But it would lack a mandate to put its values into practice or a roadmap from which to govern. The Labour party chose Ed Miliband as its leader because its members sensed he could build a radical reforming government with the potential to make a true break from the recent past. For Ed to fulfil this promise, Labour’s alternative must take shape in 2013.