A link on the brink? Labour, Jeremy Corbyn and the Trade Unions

The 2015 general election was a devastating set-back, not just for the Labour Party, but for the trade union movement too: within days of coming to power, the new Conservative government had unveiled an assault on union freedoms on a...

The 2015 general election was a devastating set-back, not just for the Labour Party, but for the trade union movement too: within days of coming to power, the new Conservative government had unveiled an assault on union freedoms on a scale unseen since the 1980s.

There could not be a starker reminder of how the fortunes of the trade unions and the Labour Party are joined. Ever since the formation of the Labour Party in 1900, it has been Labour MPs who have championed trade union rights, and Tory governments which have undermined them.

For the affiliated unions the minutiae of the election results offered some small consolation, however. Although the overall number of Labour MPs elected was far too low, the 2015 intake is probably the most pro-trade union cohort for decades. Many are former union officials – people like Richard Burgon, Vicky Foxcroft, Rachael Maskell, Chris Matheson, Melanie Onn, Angela Raynor and Daniel Zeichner – and others are unquestionably on the left of the parliamentary party.

Jeremy Corbyn’s incredible victory, then, might have been foreseen by close observers of Labour’s parliamentary selections. The composition of the new intake reflects the general sentiment of Labour Party members under Ed Miliband’s leadership, with constituency parties keen to signal a break from the Blair/Brown years.

But it is also a consequence of the huge efforts made by the big affiliates to win parliamentary selection contests. The rumours and allegations surrounding the Falkirk selection gave the impression that unions were trying to subvert Labour selection processes. The more humdrum reality is that they had the money, people and expertise to run highly professional selection campaigns, working within the party rulebook to win secret ballots.

That Corbyn was endorsed by trade unions including Unite, Unison and the CWU, offers a clear indication of how far the senior activists of some unions have moved from the Labour mainstream. If Corbyn’s tenure as leader is successful and enduring, we can expect far closer and warmer relations between the party and these affiliated unions.

On the other hand, if Corbyn fails then the future of the union link must be in grave doubt. In particular, Unite’s continuing affiliation probably depends on Corbyn’s fate: while its vast membership reflects Britain at large (and includes a great many Conservative and UKIP voters) its leadership is now well to the left of the rest of the parliamentary party.

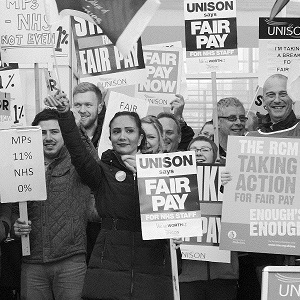

But the unions’ preferences may fast become irrelevant, because there is a far greater threat to the union-Labour link: the Conservatives’ Trade Union bill. If passed in its current form, it will effectively kill union political funds. Currently these are worth £24 million a year and are used for non-party campaigning as well as to support Labour, in the case of the affiliated unions. The affiliation fees themselves account for £8 million – almost a quarter of the party’s annual budget.

Today the levies which finance the political funds are ‘opt-out’ and union members do not necessarily pay less if they choose not to contribute. Under the proposed legislation, every member will need to ‘opt-in’ and pay extra to do so; they will have to give their permission again every five years, in a narrow three month window; and consent must be in writing, not electronically or by recorded phone call. With these conditions in place it is very unlikely that more than 5 per cent of union members will opt-in – and perhaps many fewer.

This would certainly reflect experience of the new ‘opt-in’ arrangements for union members in Labour Party elections. Some unions decided they could not justify the resource of a major campaign to sign-up their members. But even Unite, which hired large call-centres and was pleased with its performance, recruited around 70 ,000 of its 1.3 million members in Great Britain.

Labour’s union funding had already taken a hit, after the row over the Falkirk selection crisis. But the Trade Union bill and the near death of political funds will see it end almost completely, even if Jeremy Corbyn remains leader for some time. Only the House of Lords stands between the proposals (which were not included in the Conservative manifesto) and the statute book.

The whole Labour movement will unite to resist such a nakedly political assault. But this should not be an excuse for an unquestioning defence of the status quo. There are grave flaws with the way the link works, which hurt the party and the unions alike. The left needs its own agenda for reform.

A debate will be needed on the voting weight of the unions in party decision-making, considering that only 18 per cent of ballots cast in the leadership election were from affiliated supporters. But more importantly, the union-link is no longer working as a conveyor-belt to bring typical shop-floor, non-graduate workers into parliament. This is because union membership in the private sector is too low, too many union-backed candidates are professional union officials not ordinary members and the unions have been as guilty as anyone in creating an ‘arms-race’ in parliamentary selection contests, to the exclusion of candidates from diverse backgrounds.

The Labour Party stands at a cross-roads, and so does its relationship with the unions. Today the link between the leader and the major affiliates may never have been closer. But in a few short months, the power of the unions within Labour could be broken: not by the party’s right, but by the Conservatives. The union link must change or die.

A version of this article first appeared in the New Statesman supplement Working Better Together.