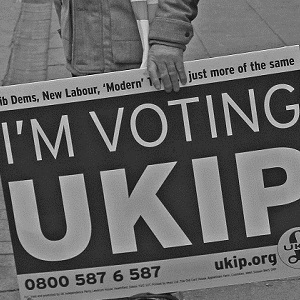

The UKIP tipping point?

Experienced canvassers will know the drill: L is Labour, T is Tory, Z is non-voter and so on. But if you have only campaigned in London, you might not have seen a ‘B’, because B is for UKIP. In other...

Experienced canvassers will know the drill: L is Labour, T is Tory, Z is non-voter and so on. But if you have only campaigned in London, you might not have seen a ‘B’, because B is for UKIP. In other parts of the country, they see little else now – as a Rotherham councillor said to me, “all we have round here is L’s, Z’s and B’s”. It is time for Labour to wake up to the threat that UKIP poses to our heartlands.

The Fabians were the first to spell out the danger to Labour in last year’s Revolt on the Left report. John Healey has recognised this threat, as has Dan Jarvis, who has argued that “Labour has been in denial for too long about the challenges posed by UKIP”. Many local parties have been combatting the challenge for some time. But the national party is yet to acknowledge its problem. Labour’s internal polling in June 2014 said that Labour general election voters who would consider UKIP were “c. 1 in 10 Labour voters. Equivalent for Tories is c. one in five in our polls … We don’t want a UKIP collapse. If they did, their vote would break 2:1 to the Tories”.

Despite the election results proving that wrong, the notion that UKIP is a threat to the Tories in the same way as the Greens are a threat to Labour continues to drive too much of our national response to Farage’s (mostly) men. UKIP and the Greens might have one seat each, but Farage is a far more serious threat than Natalie Bennett ever will be.

Ground zero

Overall, UKIP’s vote increased by 322 per cent between 2010 and 2015. But it is Yorkshire that is ground zero in the Labour v UKIP battle. UKIP came second in 44 per cent of Labour seats in Yorkshire, compared with 20 per cent in the north west. In 2010, fourth was their best result. UKIP improved its placing in 50 out of 53 Yorkshire seats (beating Labour in two) and did not lose its deposit anywhere. Nearly half the seats in Yorkshire were affected by UKIP’s rise, but the fateful eight were those, like Ed Balls’ Morley and Outwood, in which UKIP’s vote share was greater than the winner’s majority over Labour in second place.

These are the seats in which Labour-to-UKIP switchers cost us victories. And it is clear that UKIP is hurting Labour more than they are hurting the Conservatives in Yorkshire. UKIP increased its vote by 15.9 per cent on average in Labour-held seats and by 10.1 per cent in non-Labour held seats. Other seats stayed Labour but the threat is obvious: in Rotherham and Rother Valley, the increase in UKIP support between 2010 and 2015 was greater than the Labour majority in 2015. One more push and they’ll be over the line.

Scotland points the way

This threat has been growing for some time, and the beliefs that are fuelling it are even older. Before May, UKIP already had seats on eight top-tier councils across Yorkshire (Bradford, Doncaster, East Riding, Hull, North Yorkshire, Rotherham, Sheffield and Wakefield); in May they added Scarborough. The rise of the Liberal Democrats in the 1980s and 1990s shows how local government can be used to build support in once-impregnable Labour seats. The rise of the SNP over the last decade shows what happens when voters suddenly no longer feel that they have no option but to vote Labour.

The Labour collapse in Scotland was more like a volcano erupting than a tsunami breaking – the final act was brutally swift, but the build-up took years. It required an invisible local Conservative party, combined with a Labour party that for years and for many had been seen as out of touch with ordinary concerns, but which had faced little effective local opposition. It required a touchstone issue – independence – to set the lava moving. And it required one event to push the lava over the edge – a referendum in which the SNP were the only party arguing for ‘Yes’ and Labour sided with the Tories.

All these elements are currently in place for a UKIP surge in parts of Yorkshire. There are barely any Tory councillors in urban Yorkshire, let alone MPs. With honourable exceptions, many areas which have strong traditions of voting Labour have weaker traditions of Labour knocking on doors and actually speaking to people. There is a touchstone issue – immigration – which cuts across all classes and voting intentions across swathes of Yorkshire. And the tipping point is coming into view: the EU referendum. Labour will join the other parties in pushing ‘In’, leaving only UKIP arguing ‘Out’, and equating an ‘In’ vote with a thumbs-up to mass immigration. The Guardian’s Martin Kettle has asked if UKIP will be “the north’s own SNP”. It’s a sensible question.

Surely not?

All the elements of a UKIP rise in Yorkshire and elsewhere in the north are coming together, and it won’t take much to put paid to Labour’s chances of forming a government. If just a handful of the 14 Yorkshire seats in which UKIP came runner-up to Labour were to fall, our task would be almost doomed. And any surge will not be confined to Yorkshire.

The fact that UKIP’s organisation is a shambles and its leader barely credible is part of its appeal – they don’t look or sound like politicians. As another Rotherham councillor said to me, UKIP are a mess: they lack a council whip and can only agree on immigration. But that didn’t stop them taking 12 of 63 seats on the council this year, even with the increased Labour vote due to the general election.

UKIP have also tapped into a sense among many in the north that Labour is somehow southern and metropolitan – not the honest, northern Labour your grandparents voted for. It is irrelevant whether these feelings are true – it only matters how strongly they are felt. UKIP have also both fermented and ridden a growing tide of English nationalism which many in Labour have found alien, distasteful or both. Again this plays differently in the north, as Kettle points out: “To be northern and English is simply not the same thing as to be southern and English”.

UKIP’s appeal to Labour supporters is nationalist, but also class-based. As Jon Cruddas has pointed out, Labour’s vote among social liberals has held up over the last decade. It is socially conservative voters, who are more likely to be working class and to value safety, belonging and cultural identity, who have lost faith in Labour. According to Cruddas, UKIP fought Labour to a tie over these voters in May 2015. This long-term trend, coupled with the EU referendum, could be just what Farage is waiting for.

What is to be done?

Labour must combat a UKIP surge which is possible, but not inevitable. As in Scotland, only Labour can stop it. Leaving it until after the EU referendum is not an option. There are five things Labour’s leadership must do now.

First, the ‘Labour In’ referendum campaign must overshadow the official campaign. It is clear that running a joint ‘No’ campaign in Scotland was a mistake. Labour In must address early and often the UKIP line that a vote for Europe is a vote for mass immigration.

Second, the national party must recognise that the UKIP threat has deep roots and is potentially devastating. It is not equivalent to the Greens. Local parties on the front line need better help than a box of ‘More Tory Than The Tories’ leaflets.

Third, we must address people’s (often Labour voters’) legitimate concerns about immigration, but we should talk at least as much about integration. Most people are not against all immigration, but they are against all ghettos.

Fourth, we must use our newly-enlarged local Labour parties to have genuine, meaningful, conversations with voters. Insurgent parties succeed in a vacuum and fail when there is no space for them.

Fifth, our leaders must understand that symbols matter. The poppy, the national anthem, the national sports teams – all tell a story about ourselves that most people want to hear.

Appealing to Labour-UKIP switchers does not mean mindlessly tacking right: it will be based as much on authenticity, tone and narrative as it will be based on policy offers. The appeal will also have to recognise that people are voting UKIP for a variety of reasons – just as happens with any party. It must have particular resonance in the north – that is where the main threat lies. And it must present an optimistic vision of Britain’s future rather than UKIP’s promise of a better yesterday.

If we shut our ears to the rumbles of discontent from the north, then they will only grow louder. The EU referendum will provide the cause that UKIP needs to break through. They will capitalise on deep-seated concerns about immigration and cultural change. They will divide communities and end Labour’s chances of winning – and it will be our fault. B is for Bleak, and B is for UKIP.