Our common endeavour

We need a politics for the here and now, not for the then and gone, argues Phil Wilson MP

Marsden, a west Yorkshire village, seven miles from Huddersfield, grew rich on the production of woollen cloth during the 19th century.

Marsden, a west Yorkshire village, seven miles from Huddersfield, grew rich on the production of woollen cloth during the 19th century.

Bank Bottom Mill, which employed 1,900 workers as late as the 1930s, still stands solid as if hued from the rock of the hillside. The whole village feels solid. A steady-as-she-goes kind of feel, comfortable in the knowledge of Marsden’s role in the industrial revolution.

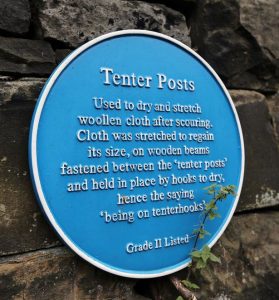

I recently visited Marsden with friends who live locally. As we strolled down Crowther Bruce Mill Road, they pointed out a round, blue plaque fixed to a solid stone wall behind solid stone posts partially hidden by shrubs and nettles. The metal blue plaque announced in clear white letters: “Tenter Posts – Used to dry and stretch woollen cloth after scouring. Cloth was stretched to regain size on wooden beams fastened between ‘tenter posts’ and held in place by hooks to dry, hence the saying ‘being on tenterhooks’. Grade II listed.”

Where there was once row upon row of tenter posts with tenterhooks in tenterfields patrolled by a walker, they are now rare. But while today their purpose is lost on many, everyone knows what it is to be ‘on tenterhooks’, defined by the Oxford English Dictionary as ‘in a state of suspense or agitation because of uncertainty about the future’.

The origin of the phrase can be traced back centuries, from when woollen cloth was a cottage industry. As the industrial revolution expanded production, the use of tenterhooks expanded too and the phrase entered everyday usage.

Today many are on tenterhooks, in a state of suspense in a world agitated by concerns: from worries about our children’s life chances to the needs of the elderly to public services being there when you need them. From the desire of many to live where they were brought up without feeling left behind, to those who want to work elsewhere to exploit their skills in a globalised economy. From North Korea to climate change. From Brexit to Trump. The list goes on. The fabric of society is on tenterhooks, stretched between the tenterposts of left and right-wing populism, ready to tear apart.

For all the old certainties offered by the left and right, in the second decade of the 21st century, uncertainty seems to be the only constant.

The choices on offer are stark. Both left and right are retreating into fundamentalism, offering theology where reason is needed. Non-believers are the new atheists. Facts now have an alternative. Experts are illiterate and square pegs can fit into round holes.

Some on the left see the future as socialism in one country, for the Brexit right it’s just about one country – and leaving the EU will see to that. Both profess an internationalist outlook, crucial in an interdependent world. But their credentials are undermined when they both want to see the UK leave international institutions upon which the fabric of world governance has hung for decades.

And here is the fracture running through left and right in British politics today. On Brexit, the foundation-shifting cataclysm facing the UK, we have a Brexit party led by Remainers and a Remain party led by Brexiteers. That is the fundamental dishonesty at the core of our politics. Both parties know it, yet dare not say it. It has become the truth that dare not speak its name. And so the fabric is pulled, not by principle, but by what is always central to the populist: a grievance dressed up in dishonesty speaking the language of whatever you want to hear.

For Labour, if we are to move on from this admission, we must seek a new political consensus grounded in values, ready to address deep-seated and urgent challenges that confront us at home and abroad. They cannot be resolved by dogma but can be distilled in the words: ”By the strength of our common endeavour, we achieve more than we achieve alone”. From Clause IV of Labour’s constitution, these words are the expression of our intent for the community of nations as well as for the communities of our nation.

The Labour party’s constitution is explicit in how we should harness economic power for ‘the many not the few’ by ‘the enterprise of the market and the rigour of competition…joined with the forces of partnership and co-operation to produce the wealth the nation needs’.

These are values which most social democrats share. The question is, how can we present these values without undermining what we believe, recognising that we can only move forward by tempering what we want eventually to achieve with what we can achieve? We believe in incremental progression, not confrontation. We are democrats, not revolutionaries. The former, not the latter, is the best means of healing a world on tenterhooks.

Human endeavour has brought about the good and the bad: the eradication of smallpox to climate change, the opportunities and woes of globalisation, the ‘global mind’ created by the worldwide web to nuclear energy and the unknown consequences of artificial intelligence.

We are responsible for all that we have done, but human endeavour without a purpose will only result in chaos. We cannot disinvent globalisation or the internet. Neither do we want to see the return of smallpox nor children working down the mines. We cannot build a wall to keep out the bad and keep in the good. A wall will not keep out a change in our climate or ward off inequality. Building walls mean shirking our responsibilities. They must be dismantled and humankind must take ownership for our actions and their consequences.

To solve shared problems, we require a shared resolve. Our common endeavour, acting for the common good, to help those who can while looking after those who cannot is our starting point.

Labour has spent more than a century pursuing this cause. The NHS, comprehensive education, the minimum wage, equalities legislation, and much more are the practical manifestation of what we believe and have gone a long way in realising our values.

To make these gains, we had the confidence of the electorate. Our policies were in tune with the times. We left the past behind and had an eye on the future. Labour was progressive, innovative and new. We offered hope, not false hope.

We did not look to the past and say: “The past is best; the future is too difficult”. In the same way, we cannot look at the issues facing us today and map out our route through the future as if we are a revivalist pop group keen to bring back the sounds of another era. That is normally the preserve of the Conservative party we should not let it be Labour’s.

I grew up in a colliery village in Sedgefield. My Dad was a miner for most of his working life. There was a strong sense of community in the village. Like Marsden, its origins lay in the industrial revolution. I remember the time when every man along my street worked down the pit. The working man’s club was the centre of social life. The village was an intimate community of shared experience. In the beginning, the miners banded together and created their own way of life, through health insurance, homes for retired miners, the local welfare hall, because there was no one else to help.

Today there are public services, as a result of progressive politics, primarily led by Labour governments. Public services, the foundation of a society that believes in the common good, are now starved of resources, not just as an act of austerity so that ‘we live within our means’, but as a deliberate policy to undermine the public service ethos, because it is not something that sits comfortably with the Conservative party. Public services need continuous investment and reform until they become, in name and intent, the public’s services.

I saw first-hand in my youth what happens when a whole industry is shut down. When the collieries closed, over time, the way of life closed down too. Of course, it would have been wrong to keep open a colliery exhausted of coal. Likewise, it was wrong to close down the local community. But that’s what happened. Such decisions nurtured what it is to be left behind.

This isn’t a phenomenon restricted to the north east of England. The rest of the industrialised world suffers from the same trend. Both northern France and Pennsylvania in the US have suffered a similar experience. Globalisation and technological change can magnify the trend.

In the developing world of the nineteenth century, Manchester saw its population double in thirty years, between 1810 and 1840. The trend continues in today’s developing world, population migration is more pronounced as people are prepared to move to centres of economic growth, with the population of Shanghai doubling between 1980 and 2010.

In the industrialised West, people are not necessarily ready to chase after work elsewhere, and nor should they have to. Family and social ties are important. Moving home from the north east of England to London, even with the offer of a job can be a financial impossibility. Freedom of movement is a fundamental principle of the EU, but only 0.37 per cent of the population move from one country to another.

Globalisation has brought great benefits. The UK is one of the main beneficiaries of foreign direct investment creating tens of thousands of jobs. Our universities attract some of the best brains on the planet and the internet has brought the world into our living room. But not all sections of our society feel as though they are beneficiaries of these trends.

Globalisation could of course go into reverse, and with Brexit and Trump’s ‘America First’ policy the possibility is there. It is no surprise that Pennsylvania voted for Trump or that Marine Le Pen received significant support in Nord-Pas-de-Calais. The north east of England voted for Brexit, despite 60 per cent of the region’s trade being with the EU. It was a failure of politics to convince those most affected by Brexit that stopping the world because you want to get off isn’t an option.

Technological innovation is hurtling towards us at breakneck speed. It is amongst us already and is one of the fundamental challenges we face and will test our ability to act for the common good.

Automation is transforming the 21st century workplace and re-defining employment. The first industrial revolution was driven by steam, the second by electric power and the third by electronic power and information technology to automate production. Now it’s the digitisation of information. The fourth industrial revolution is fusing together technologies crossing boundaries between all sectors of the economy questioning our understanding of society, individuality, democracy, international relations and more. And the combination of genetic engineering and cybernetics will one day, some believe, even question what it is to be human.

The internet and social media mean our thoughts and ideas can be transmitted around the world at the speed of light. Two billion people use Facebook worldwide each month, 1.2 billion use Whatsapp and Twitter has 328 million users. The ubiquitous handheld device means, whether we are sitting on a train or in the waiting room of the doctor’s surgery, we are more likely to be in touch with someone miles away rather than the person sitting next to us.

We take our global reach for granted, and perhaps don’t always understand why. Community has now entered a realm beyond the computer screen as we join social groups online that are worldwide rather than just down the village hall or community centre. We accept all of this. We do all of this. But the politics it is helping to generate seem to be the reverse of what was intended. Instead of embracing the world, we seem to be rejecting it. Trump wants to build a wall, the UK votes Brexit to keep out immigrants. After the general election in Germany the far-right and anit-immigrant Alternative for Germany party is represented in the Bundestag for the first time. In Poland, in November, tens of thousands protested calling for their country to be ‘Pure Poland, white Poland.’ We want to be in touch with people, as long as we don’t have to meet them. Virtual reality is fine, reality is an altogether different thing.

Previous industrial revolutions have typically disrupted a single employment sector at a time due to the specialisation of the technology, with workers then switching to an emerging industry. Information technology, is different. It is a general purpose technology and can affect every sector of the economy simultaneously. The Mckinsey Global Institute has predicted that automation and knowledge based technologies could add between $7-11 tn to the global economy by 2025. According to the World Economic Forum, the story for employment is more pessimistic. The organisation predicts that 7 million jobs will be at risk in the world’s largest economies over the next five years. However, the data on the potential impact of automation on jobs and the wider economy is mixed and often contradictory.

In 2014 a report by Oxford University academics Carl Frey and Michael Osborne predicted that over the next 10 to 20 years 35 per cent of today’s jobs in the UK had a greater than 66 per cent chance of being automated, including bus drivers and carpenters, payroll clerks and nuclear power operators. The Bank of England has predicted this could mean the loss of 15 million jobs in the UK.

On the other hand, if the focus is moved from jobs lost to jobs created, a 2015 Deliotte study concluded while technology potentially contributed to the loss of 800,000 low skilled jobs in the UK between 2001 and 2015, it helped to create 3.5 million higher-skilled jobs over the same period. The report also found, on average, that each job paid an additional £10,000 more per annum and every region benefitted.

There is another argument, which says that production will only be automated if it is profitable. After all, if automation creates mass unemployment who would buy the goods produced? Therefore, the new technologies will create other jobs, but will they, in the long term be better paid. Hans Moravec, a researcher into artificial intelligence said in the 1980s: “It is comparatively easy to make computers exhibit adult level performance on intelligence tests… and difficult or impossible to give them the skills of a one-year-old when it comes to perception and mobility.” In other words, robots can do the difficult things, but aren’t so good at the easy things. Perhaps, therefore, it is the middle-class jobs that will be in jeopardy in the future. So the lack of employment may not be the issue, but how much each employee earns.

So far, as in previous industrial revolutions, workers have been able to skill up and keep one step ahead of the machine. There are human characteristics, such as social skills, imagination, self-awareness and empathy which robots struggle to replicate. Also, a recent study by MIT stated that robot-human teams were approximately 85 per cent more productive than either alone.

However, as Andy Haldane, the chief economist at the Bank of England has rightly argued, this may not be possible in an era where ‘new-age machines will be thinking as well as doing, sensing as well as sifting, adapting as well as enacting’.

Although, the debate on employment in the world of the robot means the future is there for us to shape, the 21st century seems to be a never-ending science fiction film. Each scene is the next chapter in the evolution of artificial intelligence, robotics, genetic engineering, and cybernetics. Future trends, explored by experts, can be utopian or dystopian with the reality somewhere in between. Every day we are learning to do things faster, more often. What we do here has consequences there. The world is interdependent in a way it never was. I believe it is understandable how this creates insecurity and uncertainty, where once intimate communities are becoming atomised and solace is sought in identity politics.

Social media amplifies the grievances. Like an echo chamber in the ether, it brings people together, who may never meet, to re-enforce what they themselves already believe.

Facebook and Twitter have become the populist’s perfect dwelling place, where the woes of the world can be expounded in advert form and dogma in bite-sized chunks.

Political discourse has become chatter, not even a conversation. Social media held out the hope of enlightened politics and the spread of accurate information through effortless communication. Today, the medium is being used as a means of spreading lies, half-truths and quackery of all descriptions. Facebook acknowledges that well over 100 million US citizens, a third of the US electorate, had seen Russian promoted disinformation in the period in and around their 2016 presidential election.

Social media platforms are huge, complex and revenue-driven companies, yet to be ‘liked’ and to discuss the number of ‘hits’ a particular ‘post’ has received are phrases that have entered the lexicon of everyday use. Facebook is popular. To ban it is out of the question. To regulate is one answer. To break up social media giants is another, although this may not stop the malign use of their platforms. Responsibility needs to be taken by the companies and liberal democratic governments need to act too. If abuse is not rooted out, democracy itself could be undermined.

Today Facebook is worth over half a trillion dollars. The company’s founder Mark Zuckerberg is worth $73bn. In early 2014 Facebook purchased WhatsApp for $19 billion. Back then, Whatsapp had 450 million customers and 55 employees. The CEO of the company, Jan Koum made $6.8bn, and his co-founder Brian Acton received $3 billion.

In that one financial transaction can be seen the immensity of what faces not only our neighbour in once intimate communities, but the whole of the planet. Power and wealth concentrated in the hands of a few, using a technology so immense in its aptitude it can alter the mood of whole populations, amplify prejudice and bias, but can do so much good too. Politicians of all hues have a responsibility to step back and think afresh about the world we are creating.

At the beginning of the 20th century the Labour party came into existence to tailor the forces of the industrial revolution for the needs of working people. The Labour party was the industrial revolution’s political invention. For more than 100 years we have worked to ensure the economy and the wealth created through our common endeavour was put to use for the common good.

We have now started a new century and another industrial revolution is upon us. It cannot be tamed to our needs in one country. We do not know the full meaning of its consequences. The economic system has created banks bigger than many countries and global capital markets are now beyond the capacity of a single national government to regulate alone. War, famine and human-inspired climate change are displacing whole populations in numbers not seen since the second world war. And we know humankind has the capacity to destroy the planet in its entirety. Common endeavour is now needed worldwide and Labour’s values are needed more than ever.

British politics is tied in knots – pull one thread and the other tightens. It is never wise to be held in such a way. It is painful and the way out, for some, is complicated, so they retire to the past where they believe it is safe.

Today’s Conservative party seeks refuge in a rose-tinted vision of 1950s Britain, where they believed the need for engagement with the rest of the world was only considered necessary if conducted on British terms.

For Labour we’ve picked the 1970s, where some longed for a command economy. It is as if the last 40 years did not happen and the 13 years of Labour government were an aberration.

In the second decade of the 21st century, we need the politics of the here and now, not the then and gone.

In the 111 years since the Labour party was established, Labour has only been in power for 31 of them. Only four Labour leaders have been elected as prime minister in their own right. Our panache for opposition is well-documented and today we believe the only way to government is to watch the Conservatives collapse. Labour needs to ask of itself: are we ready? Because the challenges are great and the answers lie internationally not just at home.

The century we now face requires Labour’s politics to be more agile, alert and forward thinking than ever before because industrial revolutions can destroy political parties as well as invent them.

Trillions of pounds are hidden away in tax havens. And no wonder people feel resentful as their schools and hospitals are neglected, when they know the money is there after all.

It’s not just the overseas tax hideaways listed in the Paradise Papers that are the problem. Tech giants, such as Amazon, Apple, Alphabet and Microsoft, without the need for tangible physical presence in any country because they deal primarily with data, can move their revenue easily to more convenient tax locations, robbing nations and their populations of much needed revenue for investment in the common good.

This is yet another challenge confronting our common endeavour. We cannot face this alone. In a globalised world, size matters. That is why, remaining part of global institutions, such as the EU, gives us clout because the quest for the common good has always demanded a common response.

The major investment decisions that affect companies are taken by asset managers controlling trillions of pounds. That money is our money. We should know where it is invested and why. Pension funds, for example, should be required to detail where they invest. Votes taken by asset managers on the remuneration of corporate executives should also be in the public domain. Those votes represent our interests and should not be secret.

Ever more regulation is not the answer. What is needed is a new compact, a new understanding of responsibility and a rediscovery of fiduciary duties. Like a doctor who swears under the Hippocratic Oath to prevent disease because prevention is better than cure, those who run our financial markets and have responsibility to drive forward the fourth industrial revolution in all its forms should swear ‘‘I will remember that I remain a member of society, with special obligations to all my fellow human beings, those sound of mind and body as well as the infirm’.

We say that we live in a civil society in which we have accountable government, a free press, an independent judiciary and freedom within the law. A society that attempts to be there for us all.

Today, the concept of a civil society is being tested in a way not seen before and I do not believe we can sustain a civil society without a civil economy in which those driving forward the changes that we see understand they are also part of our common endeavour.

A civil society and a civil economy are two sides of the same coin, held firmly in the hand of our common endeavour, in a belief that all that is good should be held in common for all humankind.

We will achieve nothing until we realise that simple truth. Only then will we be able to lift the fabric of our society off the tenterhooks on the tenterposts that are causing the strain we see today.