A precious resource

The poorest in our society are not just at the bottom of the pile financially. They are also short of another valuable commodity - time. Sasjkia Otto explains

Our free time is under attack. Even before the pandemic, six in 10 people said they were struggling to keep their life organised. The most obvious culprits are familiar to us. For one, the UK has a longer full-time working week than any EU country. And for women, especially, childcare is a huge time sink: women spend 67 per cent more time than men on unpaid childcare. But apart from these, our free time is also being consumed by more and more unpaid work, or ‘life admin’, which governments and companies load onto citizens as part of cost-cutting efforts – with those on lower incomes the worst affected.

Being poor is time-consuming

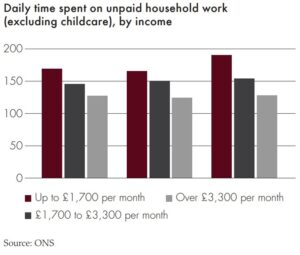

Each day, people earning less than £1,700 per month spend the equivalent of half a shift – nearly 3.5 hours – on unpaid work excluding childcare. This is an hour more than those earning more than £3,300, and 40 minutes more than those earning between £1,700 and £3,300. Disabled people also spend half an hour more than non-disabled people on unpaid work. Clearly, time poverty is not felt equally.

And time inequality has been increasing, with the average time spent on unpaid work holding broadly steady for the highest earners and non-disabled people, while increasing for the rest.

This work is comprised of small but obligatory activities like chasing service providers and querying bills – often normalised as ‘life admin’ – that tend to accumulate if you have less money or if you have additional needs associated with disability. In 2018, 46 per cent of people said they wished they could spend less time on these activities. Yet government and corporate action – or lack thereof – is perpetuating time deprivation.

Government cuts make people time poor

A lot of government decisions rely on people having the right knowledge and enough power to bring that knowledge to bear. Clearly, that tends to favour people who are more well-off. One government scheme, for example, allowed families in the south east to apply for reductions in their water bills to compensate for higher costs following the region’s water meter installation programme. Sixty per cent of eligible households missed out, and those in richer areas, who were more likely to actively engage with their utility bills, benefited most.

Despite this, government policy often adds additional pressure on lower earners to use their time to save money. For example, the recent energy bills support scheme applied savings directly to the accounts of customers who pay their bills via direct debit. By contrast, those on pre-payment meters had to take the time to apply for a voucher, many of whom had been forced onto pre-payment meters by court order. Two million energy support vouchers, totalling £125m, remain unclaimed.

Companies use algorithms and predatory personalised pricing to narrow the range of affordable products and services people can find online unless they invest time in an exhaustive search

Poorer people are more likely to interact with government services, and so pay for government cuts with their time. The complex and highly conditional benefits application process takes a significant amount of time to navigate and comply with, creating a deterrent that means millions of families are losing out on thousands of pounds each in benefits. The government has now stopped publishing statistics on benefits take-up.

The government has also removed disability benefits support for those with some capacity to work and cut per-person adult social care funding by 12 per cent between 2011 and 2019. This is despite the higher living costs of disabled people, amounting to an estimated £581 per month according to the charity Scope. The immediate effect of these cuts is, of course, financial – but they also make disabled people and their families time poor, as they have to spend more time on meeting their additional needs. Alongside outsized NHS waiting lists in poorer areas, this has only increased the barriers to finding work.

Customers pay with their time

We know the financial poverty premium means poorer households spent an average of £478 extra on essential goods and services in 2019. This is the equivalent of about an hour’s work per week on minimum wage. The time poverty premium is less well understood, but those earning less than £1,700 per month spend seven hours per week more on unpaid work than those earning more than £3,300.

Consider one common household task: laundry. There is a clear financial poverty premium here: the campaign Fair by Design estimates that a £309 washing machine will cost someone forced to pay on credit £60 extra. Some two million people do not own a washing machine at all, and so need use a launderette; for them, laundry costs 2,561 per cent more. But once again, there is also a time poverty premium: lower earners spend more time shopping around to find cheaper products, and are more likely to be affected by planned obsolescence. Using the launderette, or handwashing, are even more time-costly.

Time poverty is also exploited online. Companies use algorithms and predatory personalised pricing to narrow the range of affordable products and services people can find online unless they invest time in an exhaustive search. In the US, Amazon is currently subject to a class action lawsuit amid claims of price-gouging essentials during the pandemic, and an antitrust suit which accuses them of penalising businesses who offered lower prices on other sites.

Lower earners are often at the mercy of a small number of budget product and service providers, who can name their terms unless customers have time to mount a challenge. This is playing out across essential sectors including affordable housing, where residents are fighting service charge increases of up to 2,000 per cent and spend years trying to be heard on critical maintenance issues such as mould.

Time is money… and happiness

People on lower incomes actually spend less time in directly paid work, due in part to the UK’s working culture, which tends to reward extreme hours with higher pay. But time-intensive problems they must tackle outside the workplace add up to more than the sum of their parts and create a significant barrier to escaping poverty.

In 2021, the UK’s top decile of earners spent 11 times more on average than the lowest decile on cleaning services, and 10 times more on takeaways

Research has shown that the kind of juggling and stress about scarcity that poor people face can affect decision-making and impact productivity. Moreover, the vicious cycle of spending time to save money robs people of time and energy to invest in their wellbeing or improving their financial situation.

People who are time-poor are more prone to relationship difficulties and health problems. And while spending money to save time improves happiness, it is the richest who can most easily save time on household tasks. In 2021, the UK’s top decile of earners spent 11 times more on average than the lowest decile on cleaning services, and 10 times more on takeaways.

Time poverty also has implications for career development. Working students struggle with both extracurricular and curricular involvement, and those without the support and networks that come with affluence will spend more time seeking work.

Time is a public policy issue

Time is one of the major political and economic issues of our age. Yet it is currently a neglected consideration in government policy and delivery.

There have been some isolated interventions, such as the FCA’s new consumer duty, which aims to ensure that customers are not hindered from acting in their own interests or subjected to unnecessary delay and stress. This is due to come into force this summer. It is true, too, that the Treasury’s Green Book guidance on how to appraise policies, programmes and projects incorporates some aspects of time in economic modelling by recognising the social impact of changes in travel time.

But we should be going much further. An incoming Labour government will need a time poverty strategy that actively seeks to save citizens’ time. As part of this, the party should consider the effects of the time cost to citizens as part of cost-benefit analyses and impact assessments for new investment and legislation. This should be separated from monetary value, which cannot account adequately for the loss of this finite resource.

A time poverty strategy would be broad reaching, but should prioritise the following:

- Use good design principles to remove friction when people access public services – including applying support automatically wherever possible and simplifying applications and appointment processes.

- Review how time poverty is preventing people from participating in labour markets, and how active labour market policies could help address this.

- Ensure regulators have appropriate mandates and powers to give due weight to time as a consumer harm in market investigations and remedies.

- Review the UK’s legal framework to streamline redress processes and empower citizens to access appropriate compensation for unreasonable loss of time.

This agenda is about the fair distribution of our most precious resource. It concerns real practical problems that people – and especially our poorest citizens – face every day. Remedies for time inequality could be an effective and inexpensive way to help people take back control of their lives. Will Labour rise to the challenge?

Image credit: M Rasoulov via Flickr