A seismic shift

The SNP has been knocked from its perch – whether it can recover will depend on Keir Starmer as much as John Swinney, argues Fraser McMillan

As the electoral map of Great Britain turned red in the early hours of the 5 July and Sir Keir Starmer’s Labour party prepared for government, it soon became evident that Scottish voters had opted for a seat at the table. Having dominated elections north of the border at every level of government in the decade since the 2014 independence referendum, the Scottish National Party was dislodged by Scottish Labour all over the densely populated central belt. The nationalists lost dozens of two- way fights to their centre-left rivals, retaining just eight of 48 (notional) seats and narrowly winning one from the Scottish Conservatives.

Their vote share shrunk by a third, dropping from an imperious 45 per cent four short years ago to only 30. With the party’s support distributed evenly across Scotland, the vagaries of first past the post translated this relatively narrow second place to Labour’s 35.3 per cent into catastrophic seat losses.

Both supporters and critics of the SNP tend to view this outcome as the chickens of a 17-year tenure in office at Holyrood finally coming home to roost. Where these groups differ is over the extent to which this reversal in fortunes is self-inflicted. The seemingly inevitable tendency for incumbent parties to lose support over time is known to political scientists as the “cost of governing”, and the SNP’s apparent ability to evade paying much of an electoral price after nearly two decades in power represents an interesting research puzzle. But the party couldn’t defy political gravity forever, and two crucial dynamics explain its reversal in fortunes since a strong showing at the last Holyrood election in 2021.

The first is widespread public dissatisfaction with incumbents on both sides of the border. Most SNP politicians would bristle if told they had anything in common with the Conservatives, but the Scottish electorate used this ballot to send a message to both of the parties that have governed Scotland for the last decade and a half. Scottish voters have become increasingly willing to point the finger at the devolved government for perceived public policy failures, with the excuse that A&E wait times or falling educational standards were ultimately Westminster’s fault wearing increasingly thin. According to Scottish Election Study (SES) survey data, in 2021, 34 per cent of Scots thought the devolved administration was doing a bad job. By June 2024, that number had risen to 55 per cent. Whether this was down to perceived policy performance or the SNP’s well-documented infighting, party finance scandals and rapid-fire changes of leadership – from Nicola Sturgeon to Humza Yousaf, and then to returning veteran John Swinney – Scots are no longer content with the government at Bute House. Swinney has been in the job for just weeks and has a mountain to climb to reverse the perception that his party is out of its depth.

The second key element is a secular decline in the salience of constitutional issues. Ten years on from the referendum that reshaped Scottish electoral politics, the influence of the independence issue is fading. Again, the shift since the last devolved election in 2021 is striking. At that contest, 88 per cent of pro-independence voters cast their constituency ballot for the SNP. This near-monopoly on the Yes-supporting half of the electorate formed the bedrock of the party’s electoral success. In 2024, although final SES figures were not available at the time of writing, just 72 per cent of Yes supporters indicated they would vote SNP before the general election. The fracturing of the pro-indy coalition is ominous for the nationalists ahead of the 2026 Holyrood vote, though the residual strength of support for Scottish independence might offer some consolation.

These factors – competence and constitution – are, of course, closely intertwined. For the past year, SES data has consistently shown that, when asked about their priority for the then-hypothetical 2024 general election, voters prioritised a change of government at Westminster over the constitutional configuration of the result.

Indeed, preliminary data from our 2024 pre-election survey suggests that this tradeoff was decisive among pro-indy voters. Just 29 per cent of those whose main motivation was to get rid of the UK-wide Conservative government indicated they would vote SNP, compared to 89 per cent of those who prioritised maximising support for independence.

Such a connection between the constitution and valence politics – as well as the fluidity of voting behaviour across devolved and reserved levels – is nothing new. The SNP first came to power at Holyrood in 2007 on the back of its apparent ability to “stand up for Scotland”, a perception facilitated by its stance on independence. In 2014, Scottish independence was ultimately blocked by voters who had no objection to the idea in principle but found the proposition too economically risky. More recently, during the early stages of the Covid-19 pandemic, the view that Nicola Sturgeon’s Scottish Government was doing a much better job handling the crisis than Boris Johnson’s UK administration gave the Yes side and the SNP a sustained boost in opinion polling.

Going forward, the SNP may find it harder to convince voters it is “standing up for Scotland”. To put it bluntly, the SNP, and the independence movement more widely, benefit when Holyrood is seen to be doing a better job than Westminster. But this is the first time a pro-independence majority at Holyrood will coexist with a Labour government at Westminster – one that is likely to be much more stable than the post-Brexit Conservatives while pursuing policies with widespread support in Scotland.

The next few years will therefore exert an outsized influence on the country’s ultimate constitutional destiny, even with legal and political routes to a referendum slammed shut for the foreseeable future. If Labour fails to make a dent in support for independence or the SNP successfully claims credit for any improvements to public services and Scotland’s economic performance, it is likely the issue will rear its head again. It is not tinkering with constitutional arrangements that will ultimately save the union; rather, it is making the UK a country worth living in.

For now, though, it is important to digest that the 2024 general election is the first time since 2010 that the Scottish National Party has failed to win a nationally contested election north of the border. Whether they can avoid the same fate at Holyrood in 2026 may prove to be largely out of John Swinney’s hands. But nominally pro-independence Scots who opted in to the Starmer project will expect results, and the honeymoon is unlikely to last as long as two years. In that time, the SNP needs to show that it has internalised what voters told it in early July and identify clear areas of difference with Labour in office. If “standing up for Scotland” is what propelled the nationalists to power in the first place, it is the only thing that will sustain them into a third decade.

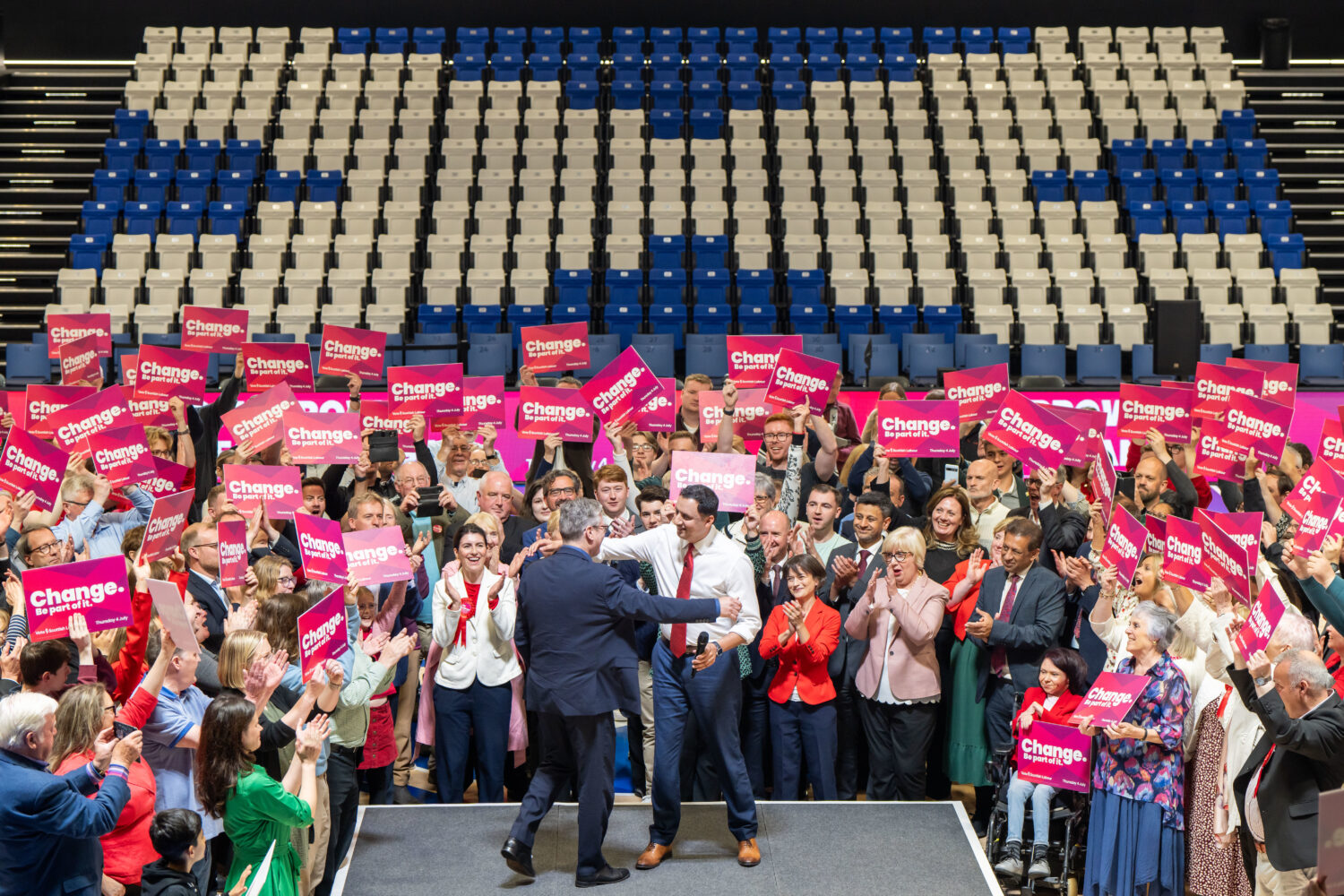

Image credit: Keir Starmer via Flickr