Baby Steps

Families with under-fives need an urgent income boost

Over a third (35 per cent) of children under five live in poverty.[i] This is the highest poverty rate of any age group. Around 15 per cent of under-fives live in ‘deep poverty’.[ii]

Our new research has set out to find some practical solutions, while also being realistic about the government’s political and fiscal constraints. We are presenting our first findings and recommendations below.

A major cause of high early years poverty is clear. The miserly social security system, which is particularly harsh and punitive following 14 years of cuts under previous Conservative-led governments. Both the two-child limit and the benefit cap have rightly been identified and criticised as major drivers of child poverty. There have also been broader cuts to social security for families with very young children – particularly under the coalition. For example, the coalition scrapped:

- Baby Tax Credit – effectively doubling the child tax credit for families with a child under one, and was worth £545 by April 2011.

- Toddler Tax Credit – a planned higher element of child tax credit for families with children aged one or two, expected to be worth around £208 a year on implementation.

- Health in Pregnancy Grant – a lump sum of £190 or the equivalent of child benefit over the third trimester to all pregnant women in the UK – providing they had received health advice.

Research from LSE, the University of York, and the University of Manchester found the Coalition government’s “tax and benefit reforms … hit families with children under five harder than any other household type”.[iii]

The consequences of poverty in those earliest years are especially damaging and long-lasting. Poverty affects a child long before birth. Research has found that babies from low-income families are smaller from around halfway through pregnancy. And the consequences can be lifelong, as a baby born in poverty is less likely to be in good health, be ready for school by the age of five, go to university, and get a graduate job with a good wage.

These inequalities are holding our country back, and without serious action to tackle early years poverty, the government will struggle to achieve its child poverty target – as well as its missions and milestones on health, opportunities, and living standards.

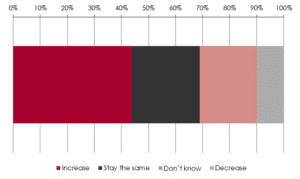

The polling we did with YouGov finds that the public expects early years poverty to get worse.[iv] When respondents were asked “looking forward over the next four years, do you expect the number of babies and toddlers living in poverty to increase, decrease or stay the same?’, 44 per cent of respondents overall said it would increase and 10 per cent said it would decrease. A quarter (25 per cent) said it would stay the same, and just over a fifth (21 per cent) said ‘don’t know’.

Figure 4: More voters think that the number of babies and toddlers in poverty will increase than decrease

Our forthcoming report will set out how the government can beat public expectations, cut child poverty, and provide an ambitious package of support for families with very young children. This will be published before the government’s Child Poverty Strategy, expected in the summer.

Today, we present our first proposals. We recommend that the government introduces:

- A new ‘baby’ element to Universal Credit, boosting the incomes of families claiming Universal Credit with a child under one by £293 a month.

- A new ‘toddler’ element to Universal Credit, boosting the incomes of families claiming Universal Credit with a child over one but under five by £156 a month.

These reforms would be in addition to the existing ‘child’ element. They would effectively double this for families with a baby, and increase it by 50 per cent for families with a young child. The two-child limit would not apply to either of these elements – which should be fully scrapped, as it is the most efficient way of reducing child poverty.

These proposed measures would benefit over one million under-fives in England and Wales, and have a significant impact on early years poverty (see Figure 1). We estimate over 143,000 under-fives would be lifted out of poverty, which would lower the poverty rate by around five percentage points to 30 per cent.[v] This would likely be the largest fall in the proportion of under-fives living in poverty since 1994/95 apart from the brief reduction seen during the pandemic. Furthermore, it would lift nearly 180,000 very young children out of deep poverty and lower the rate by around a third – to 10 per cent.

It is not a cheap policy, and we are conscious of the fiscal situation inherited by the government, worsened by impact of recent geopolitical events. It would cost around £2.4bn a year. But that is a £2.4 billion injection into the pockets of the poorest families with very young children. These policies have such a direct and significant impact on early years poverty are enough of a priority to justify that cost.

Figure 2: The total impact of introducing a ‘baby element’ of £293 a month and a ‘toddler element’ of £146 a month as part of Universal Credit

| Benefit from the reform | Lifted out of poverty | Lifted out of deep poverty | |

| Children aged under five | 1,163,000 | 143,000 | 180,000 |

| Children overall | 2,126,000 | 238,000 | 304,000 |

Considering the difficult fiscal situation, the government could initially implement the baby and toddler element at a lower rate – and increase it significantly over the course of the parliament. If the baby element were worth £86 a month and the toddler element £43 a month, around 47,000 under-fives would be lifted out of poverty – and 60,000 out of deep poverty. It would cost around £715m a year. This could be paid for by reforming the Marriage Allowance – reallocating the £400m a year underspend and restricting entitlement. As a result, the government would be better able to support the financial security of families with very young children.

Figure 3: The total impact of introducing a ‘baby element’ of £86 a month and a ‘toddler element’ of £43 a month as part of Universal Credit

| Benefit from the reform | Lifted out of poverty | Lifted out of deep poverty | |

| Children aged under five | 1,163,000 | 47,000 | 60,000 |

| Children overall | 2,126,000 | 80,000 | 105,000 |

We also recommend that the government restores the Health in Pregnancy Grant. If the Grant was available from the 12-week scan, it would be worth over £480 during a pregnancy – and cost around £290m a year.

This would effectively provide access to child benefit during pregnancy, potentially as early as the 12-week scan. It would be universal and available for every pregnancy – providing the mother had accessed antenatal advice, as under the previous policy. Around 600,000 mothers in England and Wales would benefit.

The previous Health in Pregnancy Grant showed how the government can reduce the health impacts of poverty on a child, particularly low birthweight. Restoring the Grant can deliver similar results, helping thousands of babies get a healthy start in life.

The government’s Child Poverty Strategy will need to be comprehensive. And it will need to reduce poverty for all children, not just under-fives. But as part of this strategy, we recommend they implement a new baby and a young child element to Universal Credit, and a restored Health in Pregnancy Grant as an immediate priority.

By doing so, the government will show what it stands for. Despite the fiscal and political constraints they face, they can reverse rising poverty throughout childhood, deliver economic security for families, and improve outcomes for children. A focus on early years will deliver that.

Image Credit: Sven Brandsma via Unsplash

[i] Defined as living in a household with an income less than 60 per cent of the median after housing costs based on the Family Resources Survey 2022 – 2023.

[ii] Defined as living in a household with an income less than 40 per cent of the median after housing costs based on the Family Resources Survey 2022 – 2023.

[iii] Lupton, R et al. The coalition’ social policy record: Policy, spending and outcomes 2010 – 2015, research report 4, London School of Economics, University of Manchester, and University of York, 2015.

[iv] All figures, unless otherwise stated, are from YouGov Plc. Total sample size was 4,300 adults. Fieldwork was undertaken between 18th – 20th February 2025. The survey was carried out online. The figures have been weighted and are representative of all GB adults (aged 18+).

[v] This is based on data and modelling using the Family Resources Survey 2022 – 2023 as the 2023 – 2024 data was not available for public use to model the impact of policy interventions. It does not take into account the government’s recent changes to disability benefits, due to a lack of data on the impact for families with very young children.