Capturing the moment

Arts special, vol 2: Paul Richards presents a dramatic production in three acts

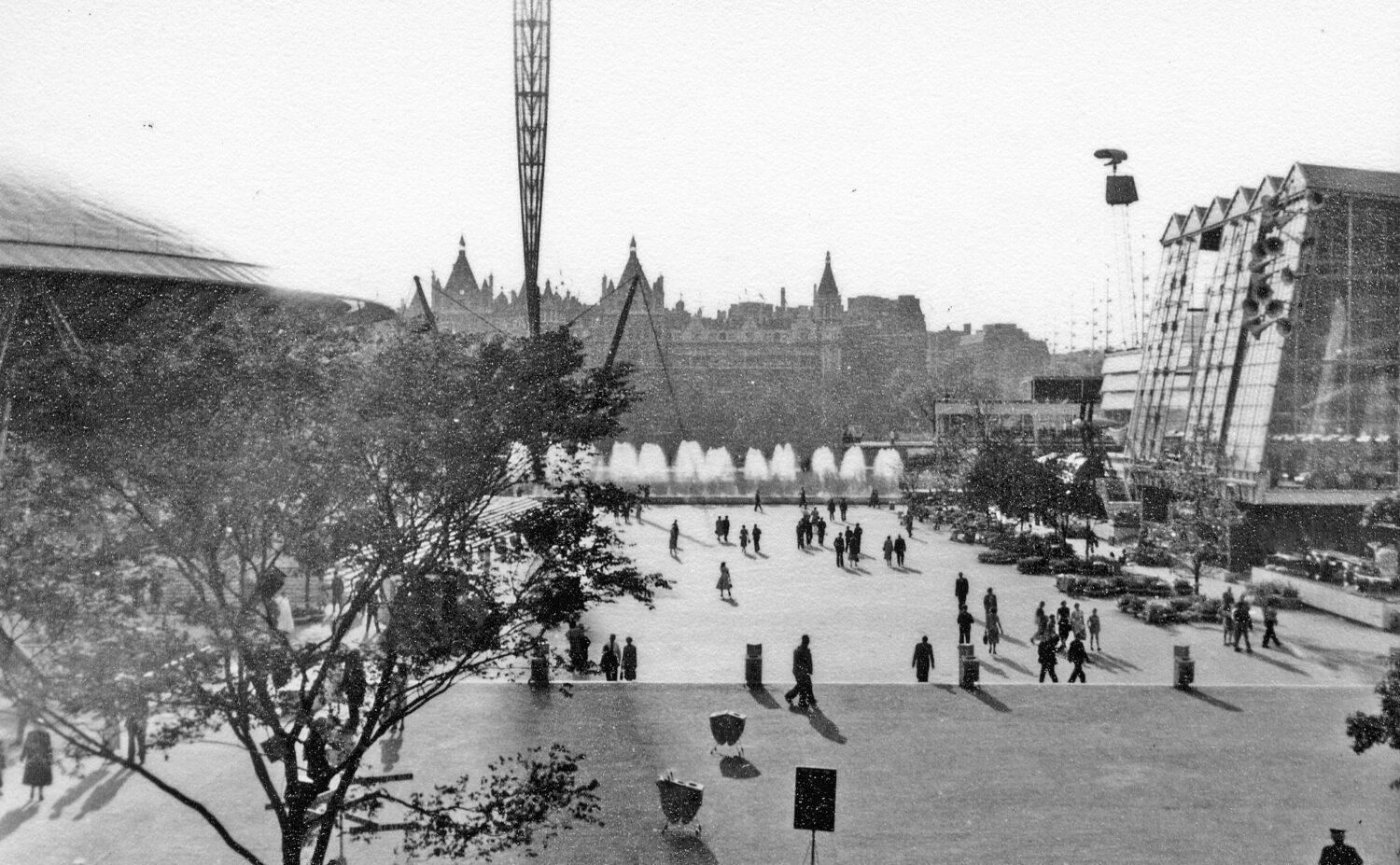

Act One: The Festival of Britain

Without the Attlee government, and especially Herbert Morrison, the 1951 Festival of Britain might have been a nostalgic rear-view look to Victoria and Empire. Instead, Morrison turned it into a celebration of British invention, science, engineering, design and architecture. It was dubbed the ‘tonic’ for a war-ravaged and rationed nation. Thousands flocked to the South Bank, and events across the UK, as the antidote to the grim, smoky, bombdamaged realities of 1940s Britain.

Labour’s landslide election victory in May 1945 was anchored on a simple premise – you won the war, now win the peace. Winning the peace required the same tools as winning the war: meticulous planning, bold decisions, scientific advances, and a national mission. The Festival of Britain was a celebration of housing estates, social progress, and what historian (and Labour peer) Kenneth O Morgan called the ‘inventiveness and genius of British scientists and technologists’. Despite Morrison’s reluctance to make it ‘political’, the festival was imbued with post-war Labour values and ideals. It chimed with the national mood in a way that, for example, the Dome in 1999 did not.

The degree to which the Festival of Britain was linked in the popular consciousness to Labour notions of progress and planning was clear in Winston Churchill’s reaction to it. On returning to Downing Street in 1951, Churchill ordered the Skylon – the 300-foot high cigar-shaped structure which symbolised the Festival – to be sold off for scrap. Nothing remains of the Skylon except the restaurant bearing its name.

Act Two: The Swinging Sixties

Labour’s defeat in 1951 heralded 13 years of Tory government, with constant changes of prime minister, a lurid sex scandal, and a growing sense of public dismay. Harold Wilson was the inheritor of this national desire for change. He was born before the Battle of the Somme, was head boy of his grammar school, went and taught at Oxford, and claimed to like HP sauce and tinned salmon. Wilson was an unlikely tribune for the Swinging Sixties, and yet that was what he became.

He made a blatant attempt to capture the zeitgeist by awarding the Beatles MBEs in 1965. According to Lennon, the band got stoned in the Buckingham Palace toilets before the Queen pinned gongs on their chests. In response to Wilson’s recognition of the Fab Four, several recipients of medals returned them in protest.

Far more significant than Wilson’s transparent PR was his legislative programme. Thanks to Roy Jenkins, a raft of laws were introduced or amended to liberalise society, from ending capital punishment, decriminalisation of sex between men to abolition of theatre censorship and reform of divorce laws. Wilson appointed Jennie Lee as Minister for the Arts, who then set up the Open University. Labour also established the National Film and Television School at Beaconsfield.

Labour’s 1964–70 government coincided neatly with the explosion in pop art, modernism, Carnaby Street, and the best music ever made. Wilson gave 18 to 21-year-olds the vote in 1969, just as many of them were turning against Labour as the party of the establishment. The Wilson governments, with their whiff of liberalism, their Post Office Tower and Ministry of Technology, and their egalitarianism, were as Sixties as Lulu or Geoff Hurst.

Act Three: Cool Britannia

By the mid-1990s, Britain was once again the centre of the cultural universe. As the Conservative government swirled in a whirlpool of sleaze, a cultural vortex arose. Blur, Oasis, Pulp, Sleeper, Elastica and Echobelly pumped out singles and packed out stadiums and together forged Britpop. The Young British Artists (YBAs) ventured from the Colony Room just long enough to rock the art world.

Blair dazzled us with talk of the ‘information superhighway’ which Labour would route through every school. Patsy and Liam snuggled under a Union Jack duvet on the cover of Vanity Fair. Football almost came home – and Labour certainly did. The election victory in May 1997 was itself a cultural event like the first moon landings: a moment of national inflection when the old was defeated and the new was born.

Blair was 43 when he walked into No 10. He played the guitar and wanted to be a rock star. At a series of Number 10 receptions, he drew in Vivienne Westwood, Ralph Fiennes, Lenny Henry, Felix Dennis, Nick Hornby, Helen Mirren, Ben Elton, Nick Park, Harry Enfield and famously Noel Gallagher, who with a nod to his hero John Lennon, took drugs in the loos. This was the most overt attempt to co-opt cultural icons into a political project since Wilson gave the Beatles their MBEs.

One of New Labour’s first moves after the landslide in 1997 was to repurpose the old Department for National Heritage into the new Department for Culture, Media, and Sport. If ever a ‘machinery of government’ rebadging signalled a change of trajectory, it was this – doing away with a department that reeked of dusty museums and stately homes and instead establishing a new artistic powerhouse. Chris Smith served as culture secretary throughout the first term, with free museums as his significant legacy. Like Attlee and Wilson, Blair understood both the need for governments to promote the arts and the tantalising possibility that arts can promote the government.

Epilogue…

Attlee and Morrison successfully used cultural events to reinforce a post-war consensus that arguably lasted until 1979. Wilson and Jenkins rode the wave of societal shifts and the white heat of technology. Blair captured the mood of the mid-90s as surely as Geri Halliwell’s Union Jack minidress. Can this new Labour government, still smelling of fresh paint, garner an encore?

Keir Starmer must embrace the technology that shapes our national culture, respect our artistic institutions, empower artists to shape new horizons, and form a creative partnership between ministers and musicians, designers, directors, architects, actors, and the people who entertain, create, and dream.

Previous Labour governments can provide inspiration on how to change cultures, and also serve as a warning: in 1951 Labour lost the election; by the late 60s, Wilson had lost the room over Vietnam and devaluation, and by 2000 the Dome was a national joke. The moment to capture the zeitgeist is fleeting. To ride the waves of rapid cultural, social and technological change, rather than be buffeted by them, Starmer must act swiftly and decisively. He will be defined by the next 24 months. In two or three years’ time, the cultural caravan will have moved on.

Image credit: Ben Brooksbank / Festival of Britain Exhibition, 1951