Democracy and the network of elites

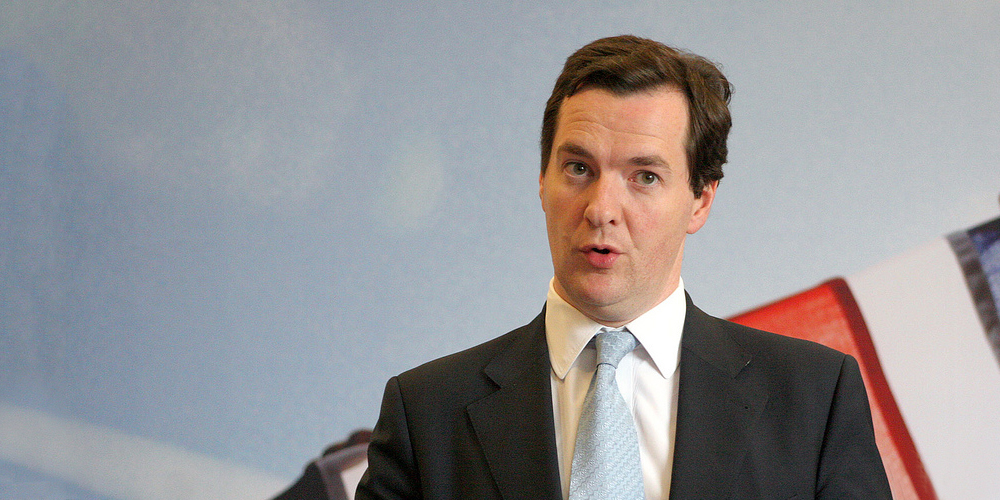

George Osborne was met with consternation and disbelief from the public, and many of his fellow MPs, upon announcing that he would be adding ‘editor of the Evening Standard’ to his roster of second jobs. But his move is hardly...

George Osborne was met with consternation and disbelief from the public, and many of his fellow MPs, upon announcing that he would be adding ‘editor of the Evening Standard’ to his roster of second jobs. But his move is hardly an exception to the rule; when it comes to MPs and peers taking up roles outside Parliament that present potential conflicts of interests, rarely is an eyelid batted. That this is so readily accepted as business-as-usual in our political system tells us plenty about how the socio-economic elite can bend the will of parliament to fit their personal ambitions, and more specifically, how they perceive their role as the representatives of the people. At the heart of concerns expressed by the public about Osborne’s second jobs is an unease that an MP in the employ of private interests may not represent their interests – and these concerns are not unwarranted.

Osborne doesn’t just moonlight with the Evening Standard. He is separately set to earn £650,000 for working one-day-a-week at BlackRock, an investment firm which he met with on numerous occasions during his tenure as chancellor. Polling by Survation of Osborne’s Tatton constituents showed that two thirds believe he should choose between the two jobs – but despite this, he has made no signal that he has any intention of stepping down as an MP. There is nothing his constituents can do to make him, until the next general election in three years time. Tatton has already thrown out one MP, Neil Hamilton, whose conduct did not meet the standards they expected of an MP. But this was when all the other parties stood down and backed Martin Bell as an independent anti-sleaze candidate.

Osborne joins a long list of MPs and peers who have leveraged their political klout to secure ‘side jobs’. Embedded in UK politics is a system that places virtually no checks and balances on big money and private interests flowing into and out of politics. It has become accepted practice for MPs – ministers and backbenchers alike – to walk through the revolving doors and straight into illustrious, highly paid jobs, particularly in the industries they once regulated.

There is also a quickly revolving door between Parliament, the civil service and corporate lobbying firms through which private interests travel, and with the huge legislative changes presented by Brexit bringing fruitful opportunities for lobbyists to influence a negotiating outcome that favours the interests of their clients.

While the people of Britain are told that the government’s negotiating position is too sensitive for them to be privy to, corporate lobbyists are afforded an inside track. Former UK European Commissioner Jonathan Hill has just taken up a post at Freshfields as a Senior Adviser, joining the likes of ex-political officials such as David Cameron’s former spin doctor Sir Craig Oliver who joined Teneo’s ‘Brexit client transition unit’, and William Hague who did the same thing. Lobbyists have also been welcomed into Parliament, with Lord Bridges, formerly the head of Quiller, who is no less than a junior minister in the Department for Exiting the European Union, while the Prime Minister’s own office is teeming with ex-lobbyists – her chief of staff, Fiona Hill, worked for Lexington Communications in between supporting May at the Home Office as an adviser and before taking up her role at Number 10, which she failed to tell the Advisory Committee on Business Appointments about.

There is a cosy relationship between many parliamentarians and a network of elites, which leads to the interests of constituents being obscured or forgotten. This is part of a much wider web, in which corporate influence over politics is almost unfettered. If you can donate a few million pounds to a political party, you can secure a place in the House of Lords. If you’re wealthy and have cash to splash towards your pet policy, then party funding loopholes can facilitate your donations in an anonymous fashion. If you’re a lobbyist, then your activities are virtually unmonitored by a wholly inadequate statutory register.

In light of all this, it is no wonder the public see politicians as being a world apart. When MPs treat their roles as representatives of the people as a CV bullet point, meant to build up business credentials, it damages public trust and undermines the idea that politicians are working for the people that elected them. Amongst other things, Brexit demonstrated that the public were fed up with the political status quo, and the persisting perception of a distant Westminster establishment harms our democracy. Brexit has left us with a divided society in which public trust in our political institutions is damaged, and one starting point for healing this divide and building trust back up is to get big money out of politics. But more fundamentally we need to reshape politics so that it responsive to the people, and a proportional representation electoral system would give constituents like those in Tatton a real voice and choice at the ballot box to kick out MPs they don’t think are doing their job.

Image: altogetherfool