Growing pains?

The truism that economic growth threatens the climate may not be so true after all, writes David Lawrence

One of the best arguments against economic growth is the impact it has on the environment. Or, at least, it was one of the best arguments until about 2009. Since then, at least for developed economies, the reverse has been true: higher growth is now associated with reduced carbon emissions. For a Labour government that is “obsessed” with growth, but has also set itself strict climate targets, this is surely welcome news.

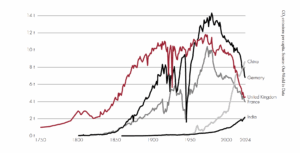

To address a potential objection head-on, the reductions in emissions among advanced economies are not because of “outsourcing” carbon-intensive production to poorer countries. The graphs below include “consumption-based” emissions, shown by the light greyline in each, which have also fallen relatively consistently, even as GDP per capita has increased.

The general story is a hill-shaped curve: as poor countries industrialise and move away from agrarian economies, GDP emissions per capita rise rapidly. But as developed economies grow, per capita emissions begin to fall again. We can track this pathway for several countries at different stages of the journey. China and India’s per capita emissions continue to rise, but their trajectories do not look so different to those of Britain, France and Germany 100-150 years ago.

Why do richer countries experience this reduction in emissions? There are several reasons, but the underlying story is that richer states can invest their wealth in decarbonisation. They can afford to move away from fossil fuels towards greener alternatives, such as wind and solar, and electrify more of the economy. This decarbonisation is not necessarily altruistic: many greener technologies, from nuclear to high-speed rail, are more efficient in the long run, but require more upfront investment. Green technologies are also often better for air quality and public health, and can reduce geopolitical dependence on the Middle East (for oil) and Russia (for gas). Advanced economies also tend to have better regulations, including clean air laws; incentives to encourage decarbonisation (like emissions trading) and discourage waste; better management of demand; more recycling; and more efficient transport and appliances.

A similar story holds at a household level. In any economy, as a poor family becomes richer, their carbon emissions tend to increase: they may buy a second car or heat a larger home, fly more, and eat things like carbon-intensive steak. But as medium-income households become richer, their emissions can plateau and even fall. They might insulate their homes or buy energy-efficient appliances, reducing energy consumption. They may move away from fossil fuels altogether by switching to electric cars, heat pumps and solar panels –which are largely the preserve of wealthier consumers, at least in western countries. In fact, in Britain, wealthier households are more likely to take the train and cycle, and rely less on cars to get around.

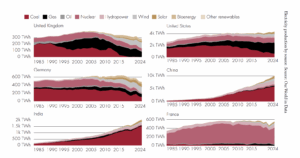

Globally, the most notable trend towards decarbonisation has been in electricity generation. In this respect, the UK is a leader: coal use for electricity has fallen to zero, and gas is gradually being replaced by wind and solar. Even if Ed Miliband does not hit his goal of clean power by 2030, UK electricity use is already mostly from non-fossil fuel sources. The main challenge now is moving more consumption onto the grid – switching from petrol to electric cars, and gas boilers to heat pumps. Perhaps counterintuitively, increased electricity demand at the right times (i.e. not during winter peaks) can reduce the cost of electricity per unit, since it means that there is more revenue to cover large transmission and other fixed costs. The cost of renewables, at the margin and at the right times, is small: we should make the most of this.

Germany and the US, while more reliant on fossil fuels, have seen similar reductions. China, despite investing heavily in renewables, is still dependent on coal, as is India, which has a more typical ‘energy mix’ for an industrialising country. France, which made a savvy early bet on nuclear, has had a close to carbon-free grid for decades. The point here is not to shame emerging economies: they are following the exact same fossil use path as the UK, US and most of Europe during our periods of industrialisation. Indeed, wealthy western countries are far more to blame for the climate crisis than non-western emerging or middle-income countries. The point is that for wealthy countries like the UK, growth is not only negatively correlated with carbon emissions, but may be actively helpful for decarbonisation. It would be a mistake to claim that the solution for climate change is for wealthy, western countries to grow less, as is advocated by some ‘degrowths’, and indeed many more mainstream progressives.

To make this more concrete, consider the biggest barriers to reducing emissions in Britain. Two of the biggest sources are domestic transport – i.e. petrol cars – and “buildings and product uses,” which mainly refers togas-based heating of buildings. In both cases, we already have the technology to go green. Electric cars not only exist, but are in many ways a superior product to petrol cars – they’re quieter, accelerate quicker and, in the long run, can cost less to run. Similarly, heat pumps could entirely replace gas boilers, with the bonus that they can provide air cooling in the summer as well as heating in the winter.

But in both cases, the biggest barrier to EV and heat pump adoption in Britain is cost. Households struggle to cover the upfront cost of buying an electric car or heat pump, even though running costs for both can be low. The British state does not have enough fiscal headroom to subsidise EVs and heat pumps, or invest in the infrastructure for charging points across the country. With a couple of exceptions, the countries with the highest EV adoption in Europe tend to be the wealthiest: places like Norway, the Netherlands and Switzerland have far higher adoption than Italy, Spain and Greece. Likewise, it is the wealthiest households that are most able to pay for a heat pump, or install solar panels on their homes.

Wealthier countries with greater state capacity can also invest in greener infrastructure across the board. Investment might be in production (subsidising nuclear or wind farms, for instance); grid connections and transmission; adoption of technologies such as EVs and heat pumps; or better demand management (i.e., using insulation, batteries, smart meters and incentives to balance the grid).

Growth can also change our lifestyles in ways that reduce emissions. Investing in bicycle lanes, trains, trams and metros can transform our cities by reducing car dependence. The housing policies which are best for growth – such as residential annexes, street votes, and resident-led estate renewal – tend to be good for reducing emissions too, because they focus on densifying urban areas, which encourages walking and public transport over car use. Densification tends to mean more homes taking up less land, using less energy, and connecting workers to higher productivity jobs and delivering a high-quality of life. Sprawl is the enemy of both growth and conservation.

Then there are more speculative, innovative ways in which growth can help the green transition. As an economy grows, so does the amount spent on research into green technologies. A breakthrough in nuclear fusion, sustainable aviation fuel or next generation geothermal energy could be transformative for helping countries go green – and speed up the transition in developing economies, too. New research could even reduce the carbon impact of agriculture if we find better alternatives to meat.

All this means that there need be no conflict between tackling climate change and the pro-growth, “build baby build” agenda that has been embraced and espoused by this government – so long as we build in the right ways. This should be good news for everyone – eco-warriors and ‘yimbys’ alike. But taking advantage of this alignment of interests will require change from both sides of the debate.

Those of us who care about growth should stop framing it as being in conflict with environmental objectives. Environmentalists, for their part, should welcome higher GDP, and focus their efforts on ensuring this GDP is “spent” on decarbonisation. In particular, environmental groups should welcome several pro-growth planning reforms, such as those that encourage densification, which reduces urban sprawl and increases average home efficiency. They should also support making it easier to build renewable energy, nuclear, grid connections, transmission and public transport – the infrastructure of modern, green economies.

It will always be tempting for politicians to have a fight. Sometimes, it’s helpful to have an enemy –whether it’s “builders versus blockers”, or the bats and newts that increased costs for HS2. But true leadership means identifying win-wins: policies that can command broad, durable support. When it comes to growth and climate action, a free lunch is on the table: we just need to grasp it.

Image credit: Mike Bird via Pexels