New dimensions

The old left-right divide means less and less as voters struggle to fit themselves into party boxes. If the centre-left is to revive, it must work within this new landscape, as Paula Surridge explains.

The last 12 months have seen much talk of the ‘politically homeless’, and the possibility of new ‘centrist’ parties is touted almost weekly. But evidence from elsewhere in Europe suggests that the centre ground in politics is becoming increasingly difficult to sustain. Has there been a retreat from the centre among British voters? How can we best understand how voters are positioned?

The 2017 general election in Britain seemed to cast doubt on the processes that had been observed in earlier elections. The rise of third and fourth parties in 2010 and 2015 dramatically reversed as the two-party share of the vote rose to its highest level since the 1970s. Underneath this apparent return to the two-party system there has been fragmentation in the positions of voters which does not neatly fit into our understanding of a single ‘left-right’ dimension. We cannot understand the ‘centre’ of British politics (or indeed the left and right) only with reference to this single dimension – a ‘new’ set of values among voters is also important and these values have been polarising. This has led to a fragmentation of both the left and right which will continue to contribute to volatility in the behaviour of voters struggling to fit their value positions into party boxes organised by a weakening political logic.

There are two ways in which we can understand the positions of voters. First, we can measure their values using attitudinal items, by measuring two sets of values: those associated with the traditional left-right divide about economic justice and fairness and those associated with a ‘liberal-authoritarian’ divide. In order to allow for comparability over time, the items used to measure these scales are:

Economic left-right dividing issues:

• Ordinary people get their fair share of the nation’s wealth

• Ordinary people get their fair share of the nation’s wealth

• There is one law for the rich and one for the poor

• There is no need for strong trade unions to protect workers’ rights

• Private enterprise is the best way to solve Britain’s economic problems

Liberal-authoritarian dividing issues:

• Young people don’t have enough respect for

• Young people don’t have enough respect for traditional values

• Censorship is necessary to uphold moral values

• We should be tolerant of those who lead unconventional lifestyles

• For some crime the death penalty is the most appropriate sentence

• People who break the law should be given stiffer sentences

In each case the response options are five-fold: strongly agree, agree, neither, disagree and strongly disagree. Scales are created by taking the average of the positions across the items, after correcting for the direction of the question wording. Each of the scales run from 1 to 5 with a notional mid-point of 3 (the result of giving a ‘neither’ response to all the items). In order to understand groups of voters on these value dimensions, these scale positions are further divided to produce a ‘left’, ‘centre’ and ‘right’ group on the left-right scale and a ‘liberal’, ‘centre’ and ‘authoritarian’ group on the liberal authoritarian scale.

The second way we can understand the positions of voters is by using their own self-assessment of their political position. This is usually done by asking people to place themselves along a single left-right dimension measured as an 11-point scale with 0 the most left-wing position and 10 the most right-wing.

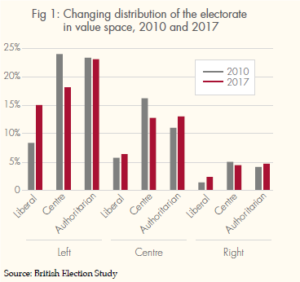

Comparing 2010 with 2017 in figure 1, the value scales suggest a polarisation of the electorate and an emptying of the ‘centre’ but this is not on the economic left-right dimension. On this economic dimension around 55 per cent of the electorate were in the left group, a third in the centre group and 11 per cent in the right group in both years. In all cases though there has been a polarisation within these groups, such that the ‘centre’ group in each case is smaller in 2017 than it was in 2010. On the ‘left’ of the economic dimension this is largely the result of a move to more liberal positions, while elsewhere on the economic dimension there have been small increases in both the liberal and authoritarian positions at the expense of the centre.

This highlights the difficulty in talking about ‘the centre’ of British politics. While the overall distribution of the electorate on issues of economic justice has been relatively stable over the last 10 years, there has been a noticeable polarisation on issues of authority and tolerance. More people have both liberal and authoritarian attitudes. This is most stark on the ‘left’ of this economic dimension and highlights the challenges parties of the centre-left have faced both in the UK and elsewhere. Essentially, it has become increasingly difficult to form broad left-leaning electoral coalitions as the voters look to express their values across multiple dimensions. Many of the most salient issues of our time do not sit easily along the old left-right divide and are much more closely related to the polarising liberal-authoritarian divide. The vote to leave the European Union is one such example. Leave and remain voters are barely distinguishable in their positions on the traditional left-right divide but are poles apart on liberal-authoritarian values. Similarly attitudes to immigration, gender identity and the role of ‘experts’ are all strongly related to this liberal-authoritarian divide.

While it is important to recognise that economic values do continue to structure voting behaviour in general elections in the UK, they do so in part due to a party system which does not offer space for these other values around social issues like immigration and criminal justice to be fully represented. Elsewhere in Europe (most recently in Germany and Sweden), where the party system has allowed, we have seen fragmentation into groups much more clearly defined by these combinations of economic and social values.

While it is important to recognise that economic values do continue to structure voting behaviour in general elections in the UK, they do so in part due to a party system which does not offer space for these other values around social issues like immigration and criminal justice to be fully represented. Elsewhere in Europe (most recently in Germany and Sweden), where the party system has allowed, we have seen fragmentation into groups much more clearly defined by these combinations of economic and social values.

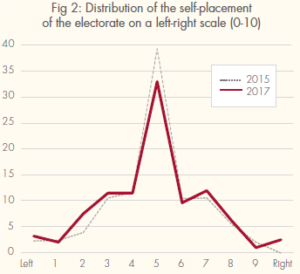

This emptying of the ‘centre’ is also evident if we compare how people place themselves along a dimension which runs from left to right. The period between the 2015 and 2017 elections is relatively short, yet between these two elections there is a fall in the proportion of the electorate placing themselves in the ‘centre’ (whether measured as the single mid-point of 5, or as the combination of central points 4, 5 and 6).

The chart also shows that the kick out to the ‘left’ end of the scale is a little greater than that to the ‘right’ end of the scale. This may seem puzzling; the value scales considered in figure 1 seem to suggest stability on left-right issues, with around 55 per cent of the electorate on the ‘left’. But it reflects the way in which ‘left and ‘right’ are routinely used in our political discourse to refer to both economic and social issues. Those with very liberal positions on the liberal-authoritarian scale are the group which place themselves most to the ‘left’ when asked to self-identify. The push out to the left and right in 2017 reflects the shrinking of the centre ground, that this is more pronounced on the left further reflects the increasing proportion of the electorate with liberal social values.

The evidence presented here helps us to make sense of the changing, yet on the surface stable, landscape of British politics. The political system which has so long been aligned broadly along a single left-right divide represented by a single party on each end continues to structure voting decisions. But the positions of the electorate are much more complex than this suggests and the volatility that led to the surge of the Liberal Democrats in 2005 and 2010 and the rise of UKIP in 2015 is still there.

Constrained by an electoral system which does not easily accommodate value positions on more than one dimension, voters struggle to fit themselves into boxes which only partly reflect their preferences. The challenge for the centre-left is how to work within this new landscape.

The electorate are on average positioned on the left economically and so are open to appeals from left-wing parties. But increasingly this is not enough. As issues which connect with a different set of values become more prominent in our politics, some voters are left stranded between their economic and social values finding that there is no natural home for them. Talk of new centre parties fails to properly engage with this as it seeks to position itself between the two main parties economically but with a firmly liberal, pro-European stance. This is not where the voters are positioned. Only by engaging with where voters are positioned on social issues can parties of the left begin to recapture ground from the populist (authoritarian) right and understand why they are also losing ground to parties further to the left, both economically and socially.