Power and principle: Labour as a government-in-waiting

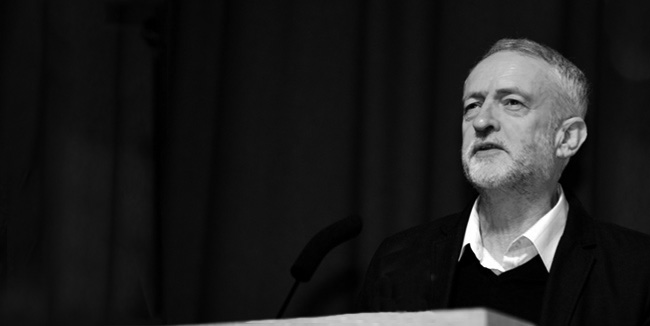

In September 2015 Jeremy Corbyn was elected leader of the Labour party by an overwhelming 59 per cent of the electorate. His candidacy had, at first, been considered something of a token gesture but his campaign then...

Labour as a government-in-waiting

In September 2015 Jeremy Corbyn was elected leader of the Labour party by an overwhelming 59 per cent of the electorate. His candidacy had, at first, been considered something of a token gesture but his campaign then took off and the campaigns of his rivals appeared to falter. He attracted media attention, benefitted from the introduction of £3 registered supporters and the frequent media interventions by the likes of Tony Blair.

What his victory showed was a clear gulf not just between Labour activists and MPs but also between Labour activists and the wider electorate. Despite his popularity within the party, Corbyn started off his leadership with record low personal opinion poll ratings and the gap between the Conservatives and Labour remained wide until well into 2016. With the recent splits in the Conservative ranks over the EU, the resignation of Iain Duncan Smith and the revelations of the Panama Papers, the Tory poll lead has now disappeared. However, a more detailed analysis of the latest polls still paints a challenging picture. His net satisfaction rating is still worse than that of David Cameron, despite all of the current problems faced by the Tories. At this stage in the last electoral cycle, Labour under Ed Miliband had an 8-10 point lead.

There is, then, a clear distinction between the views of the electorate and the parliamentary party on the one hand and of a large section of the party activists on the other. It is a central contention of this article that Labour activists seeing the maintenance of their principles as more important than gaining electoral support amounts to the politics of irresponsibility. There is no scope for compromise with the electorate.

There is nothing new in this. Roy Hattersley and Kevin Hickson have argued that at key moments in the party’s history it is assumed that there is a trade-off between power and principle caused by the lack of faith in its ideology. Either the principles have to be diluted in order to win elections or else it is better to stay in opposition where the principles are not jeopardised by the compromises that power necessitates.

For New Labour the reason why the party had lost successive general elections was because it was out of touch with mainstream voters who regarded socialism as obsolete. The party sacrificed long-cherished policies in order to get into power as the leadership courted the right-wing press and contemplated a formal electoral pact with the Liberal Democrats. Once in power the idea of the ‘progressive alliance’ disappeared but the party was cautious so as not to risk unsettling the markets or the electorate. This is not to say that New Labour did not have social democratic achievements; it clearly did, but often these were hidden. Social democracy would have to be something done to the people not with them. The party in power, despite having a large parliamentary majority, remained cautious as it sought the historic achievement of a second, and then a third, full term. To its critics on the left, New Labour was simply the continuation of Thatcherism, wedded to the central notions of neoliberalism. The government was bound to disappoint and thus the party followed its historic pattern.

Activists tend to be to the left of the electorate. Elected representatives are viewed suspiciously as they seek to meet the expectations of the electorate and the cry of ‘betrayal’ is never far away. Every Labour government has, to a greater or lesser extent, disappointed the active membership. This was certainly true of the first two Labour governments. Lacking parliamentary majorities they were impotent. Some in the party talked openly about the need to overthrow, or at least circumvent, the parliamentary system. Despite being widely regarded as the most successful Labour administration, even the Attlee governments of 1945-51 faced its critics from the left of the party who believed that foreign policy was too closely aligned with the US, that Britain should not have an atomic weapons capability and that Labour’s domestic policy was more about managing capitalism than introducing the socialist transformation they craved. Left-wing criticism of the 1964-70 Labour government was only curtailed by the return to office in 1974 and following the election defeat in 1979 the party moved radically leftwards under the dominant personality of Tony Benn, who launched an all-out attack on the government of which he had been a part. Not only would the party have to endorse more radical left-wing policies but its elected representatives would be subject to the greater control of the members.

Despite appearing poles apart, it is perhaps better to see New Labour and the Labour left, of which Corbyn is the modern day manifestation, as mirror images for both accept the trade-off between power and principle.

Writing in the late 1950s, Richard Crossman argued that it was better for the Labour party to remain in principled opposition to the Conservatives and await the inevitable crisis of capitalism at which point the party could return to office with a genuine socialist programme. In practice this may mean being in opposition for longer than in office, but what was the point of being in power anyway if the party had abandoned all its principles to get there? Against this, the followers of Hugh Gaitskell argued that this was an irresponsible position to adopt since in the meantime those who needed a Labour government would be at the mercy of the Conservatives. Better to be in power with at least some of your principles than being impotent in opposition. It was this to which Denis Healey was referring when he complained that: “There are far too many people who want to luxuriate complacently in moral righteousness in opposition”.

Later, Tony Benn maintained that successive General Election defeats in the 1980s and 1990s were the fault of Labour moderates who had watered down the party’s socialism in an increasingly desperate attempt to get into power. The electorate no longer knew what Labour stood for. It would be better to remain on the political left than seek to compromise. The same argument has reappeared today. What difference, after all, would a right-leaning Labour government make when compared to a Conservative government forced to lean to the left in the face of a strong oppositional politics under Corbyn?

Corbyn’s Credibility

Jeremy Corbyn gains his credibility as an authentic politician from the enlarged Labour party membership following his unanticipated victory during the 2015 leadership election. Corbyn’s appeal derives from his offer of a break from the professionalised style of leadership, synonymous with Blair and his successors. His appeal is anti-professional. For example, his leadership bid was given a significant boost following the controversy over the welfare vote in the House of Commons. After mainstream leadership candidates followed Harriet Harman’s instruction to abstain, the Corbynite narrative was seemingly confirmed: that Burnham, Cooper, and Kendall were ideologically complicit with Conservative austerity. Within this context the size of Corbyn’s support grew and with it his credibility as an authentic leader who opposed, rather than abstained.

Corbyn’s supporters were highly enthused by his campaign. His hustings attracted huge support. In Camden, Corbyn addressed a rally of over 1,500 people. Such meetings were used by Corbyn and his supporters to restate classic socialist values to an audience who had never been exposed to them before. Indeed, the disproportionately youthful audiences listened with great interest to Corbyn’s criticism of the Conservatives and, of course, the previous leaderships of Ed Miliband, Gordon Brown, and Tony Blair. Others, such as the former Militant supporter Tony Mulhearn or the Guardian journalist, Owen Jones, spoke before Corbyn to ensure the large audiences were as receptive and emotionally charged as possible. These meetings became fundamental in constructing Corbyn’s claims to be an authentic contender. As leader, he argues they illustrate his ongoing support given the size of his mandate.

In contrast to his supporters in the country, the parliamentary Labour party are left with a leader who, for them, lacks the credibility needed to lead them in the Commons. Some in the PLP such as Diane Abbott, Dennis Skinner, and Clive Lewis are amongst the minority who nominated Corbyn believing him to be the best candidate, however the majority of the PLP are opposed to this view. Furthermore, part of the rationale for some of those nominating him for a debate was so that a post-Miliband, moderate leader would be able to define their manifesto in opposition to the arguments of the left. Tactically, this was an attempt to replicate Diane Abbott’s inclusion in the 2010 leadership election, who gained only 7.42 per cent of the vote, thereby dropping out after the first round. However, given the changes to the leadership rules enacted by Miliband, an influx of affiliate members flooded the selectorate, who sought to change the Labour party into something more akin to a protest movement.

In terms of a credible party management strategy, Corbyn attempts to appeal beyond the PLP, or indeed the normal membership. To facilitate this, the group Momentum was formed as a successor to Corbyn’s campaign in order to continue pushing for his style of political protest and conception of socialism. Momentum operates as a grassroots organisation designed to manage the strategies of the constituency parties, whilst also trying to bridge the gap between the left within the party and those on the outside, such as Left Unity. Also, part of this strategy is to argue that elected constituency party members and Labour MPs are delegates of the membership, rather than representatives of their constituencies. The argument is that those who are elected serve as instruments of the members and the leader. This puts the parliamentary party into a highly problematic position given they are accustomed to a deliberative process.

At present, Corbyn’s leadership of the Labour party is continuing to be a source of controversy for the parliamentary party. This is because his style of leadership sees his constituency as those who supported him in the leadership election, from groups like Momentum, and the broader membership of the party who are sympathetic to his arguments. This is where he derives his credibility. However, from the point of view of the parliamentary party, Corbyn is likely to continue to lack credibility in the long term. This is because of the hostility which has publically been on display from both sides. It seems highly unlikely that Corbyn will ever lead the Labour party as a unifier. Indeed, his recent decision to address a CND rally rather than a Labour In EU meeting illustrates his priorities as leader. Consequently, whilst it is fair to say Corbyn has a considerable mandate and credibility from a significant portion of the party, Labour will remain at the mercy of a Conservative statecraft which will continue to portray Corbyn’s leadership of the Labour party as chaotic, and Corbyn himself as unfit to lead a credible party of government.

A Credible Alternative

The following headings provide an overview of the current direction of policy from the Labour leadership along with suggestions considered to have a broad appeal, thus both principled in their commitment to socialism and focused squarely on the pursuit of power, maintaining Labour’s position as a ‘government in waiting’.

Economic Policy

Under Corbyn, Labour is an anti-austerity political party arguing for higher taxes and public investment to eradicate the deficit and stimulate growth in the British economy. In part, this is a decision influenced by the belief that Labour and the Conservatives had become indistinguishable, that the electorate has moved to the left and consequently anti-austerity politics are popular amongst voters. Such a reading of the current state of British politics is highly questionable. By 2020 the British people will have experienced ten years of austerity and although they may think the spending cuts are unfair, the polling evidence suggests that they have believed the cuts to be necessary since 2010.

Consequently, the Labour Party must acknowledge the need for fiscal responsibility and a degree of spending cuts to win the trust of the electorate to run the British economy. Yet, within these constraints exists an opportunity to transform the British economy through rebalancing; moving away from financial services to new forms of industry, away from the south east to the rest of the UK through a modern regional policy, spreading opportunity across the United Kingdom. This can be supplemented by national public works projects including a full backing of High Speed Rail (HS2), which far from ‘turning northern cities into dormitories for London’, offers towns and cities across Britain the opportunity of regeneration and greater business ties, along with a boost to employment both in building and running the service. Recent announcements by John McDonnell suggest that he is aware of the way the party is perceived on economic matters, but it is doubtful that a left-wing leadership will ultimately convince the electorate on this crucial aspect of economic policy.

Social Policy

Corbyn has emphasised his commitment to affordable house building for social tenants, a £10 an hour living wage, returning academies and free schools to local authority control and the scrapping of tuition fees. The Labour leadership would do well to advocate ‘responsible welfare’, helping to shift the argument away from ‘strivers and shirkers’ to the restoration of the principle of universal social insurance, a welfare state which is there for everyone in times of need and which is based on the contributory principle. On the matter of health, Andy Burnham’s integrated ‘whole person care’, addressing physical, mental and social needs through the integration of health and social care is radical and has the potential to better the lives of patients and families.

Corbyn shares the view of many within the party on the issue of immigration into Britain, that benefits outweigh the downsides and further ‘open’ and ‘progressive’ policies should be pursued. However, the Labour party must consider the political and electoral implications of the rise of the United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP) and their appeal to the socially conservative working-class, who require economic protection. This can be done by advocating stronger and tighter border controls and legislation to avoid the undercutting of wages by immigrant labour, which in turn would be helped by the introduction of the living wage. Furthermore, the Labour Party should promote policies to foster the assimilation of immigrants into the British way of life, aiding community cohesion, whilst recognising the desire of the working class to express its own identity.

Defence and Foreign Policy

Corbyn’s personal views on security and military intervention have provoked controversy, including his reluctance to condone ‘shoot to kill’ and extending British military action into Syria. Arguably it is on these issues of foreign and defence policy where Corbyn lacks the most credibility. The upcoming vote on renewing Britain’s nuclear deterrent and Corbyn’s unilateralist stance will once again expose divisions between the leadership, MPs and membership. Whilst an argument can be made that Trident does not best serve our military interests and its importance has declined since the end of the Cold War that is no guarantee the British people will vote for a political party opposed to its renewal. The current comprehensive defence review should consult widely and thoroughly in the Labour party and beyond, weighing up all the arguments, before committing to a policy acceptable to the majority of the parliamentary Labour party.

Based on the merits of the particular case not previous conflicts, the United Kingdom must fulfil its moral and international duty, and deploy military force to bring about peace and justice. Hilary Benn’s impassioned speech on extending military air strikes into Syria was based on Labour’s internationalist tradition. Should the Labour party be perceived, accurately or not, to be weak on matters of defence and national security the electorate will deem the party unable to fulfil the first function of government which is to protect its citizens, at home and abroad. Labour must move beyond the legacy of Iraq, rather than using it as a justification to look inwards.

Conclusion

The Labour party, if it has ambition to be a ‘government in waiting’, must formulate policy that is deemed to be credible and deliverable to build a broad electoral coalition. Whilst the ideas outlined above are by no means exhaustive they do offer a way of moving forward that the Labour leadership should consider. A present danger exists under the current Labour leadership that policies devised will, instead of addressing the concerns of the wider electorate, take the comfortable option of appealing to its core voters and supporters – a section of the electorate insufficient to deliver a majority. Indeed, the British public will look on in bemusement at best and horror at worst, questioning whether the Labour party is a glorified protest movement or serious party of the British state, capable of commanding the economy, reforming the health service and possessing the will to defend the realm. If the latter road is chosen, the cultural stereotype of the Labour party that enjoys the comfort of opposition, not the difficult decisions of government will re-emerge, for 2020 will result in electoral defeat, and the people who need a Labour government will be let down.