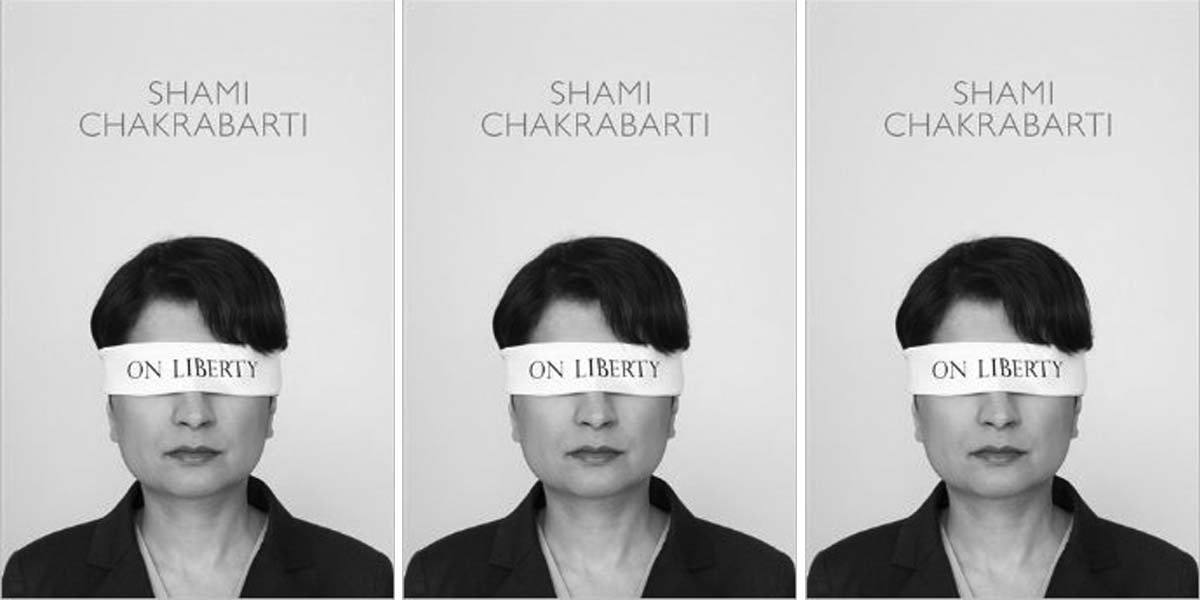

Review: On Liberty by Shami Chakrabarti

Like John Stuart Mill’s 1859 treatise of the same name, On Liberty is a timely wake-up call. But while Mill was an establishment figure deploying the philosophical reasoning of utilitarianism to decry tyranny, Chakrabarti, having forsaken the establishment, engages in...

Like John Stuart Mill’s 1859 treatise of the same name, On Liberty is a timely wake-up call. But while Mill was an establishment figure deploying the philosophical reasoning of utilitarianism to decry tyranny, Chakrabarti, having forsaken the establishment, engages in a direct attack from the frontline. Formerly a Home Office high-flyer, as Director of Liberty she is driven by an articulate passion for justice, decency and human rights, and speaks out against growing numbers who attack Britain’s human rights framework, whether out of ignorance, contempt, fear or (perceived) duty.

Not for her the festina lente of the Fabians! She is in a furious hurry and, paradoxically for her cause, not a natural taker of prisoners. Total intellectual and legal destruction of the enemies, as she unforgivingly sees them, is obviously her objective. The book is a real page-turner.

The target list for her wrath is formidable, and includes (inter alia):

- British politicians who rail against “unelected” judges – demonstrating a lack of “understanding of the foundations [and checks and balances] upon which our democracy rests”;

- Discrimination which results in resentment and alienation, and which can then feed into support for terrorists and fanatics;

- Authorities who do not follow through on “existing or potential policy measures that would better equip them in complex anti-terror investigations and trials”;

- ASBOs, an ineffective but inexpensive sop to those plagued by anti-social behaviour;

- Legal aid cuts – which have already resulted in many important test challenges to bad practice and abuses of power not being brought;

- Deportations with Assurances – with the Memorandums of Understanding “not worth the paper they’re written on”;

- Secret tribunals undermining the rule of law by “making it too complicit with administration in general and the secret state in particular”;

- Those politicians who denigrate and dehumanise immigrants, asylum seekers and refugees with their cynical use of ‘divide and rule’ tactics in an attempt to distract the electorate from a failure to deal with the real social, economic and practical inadequacies and challenges;

- “Tough on terror” policies being adopted as populist “vote-winners”, with a desire to send out a signal of strength and decisiveness, rather than because of their real operational benefit.

Chakrabarti rightly identifies the proposed extension of pre-charge detention to 42 days – passed in the Commons under the previous government but firmly defeated by the firm stand in the Lords – as one of the red lines. It was deeply disturbing to hear Ministers at the time argue in Parliament that it had to be done because the police said so. Of course, government should take very seriously what the police argue as essential, but it is ultimately up to accountable ministers to evaluate this advice and come to their own conclusion as to its validity. In any case many police – not least some of those in the front line – believed it was a wrong policy because it made more difficult the task of winning invaluable support for their work in, for example, the Islamic community and could well create folk heroes amongst the disaffected young.

Chakrabarti sets out very convincingly – and very worryingly – the current direction of travel. In response to terrorism we are steadily removing the cornerstones that make Britain a country worth defending. The recent Counter-Terrorism and Security Bill appears to be, sadly, yet another case in point.

Many seem to have forgotten that the European Convention on Human Rights is not just about creating a nicer kind of society: it was forged by the experiences of the Second World War and the recognition that human rights are a muscular imperative for enduring stability and security. Valid human rights are by definition not just British, French, German or whatever, they are universal rights “contingent on humanity not nationality”. British politicians, officials and lawyers played a key part in recognising this and drafting the convention and other related legislation.

It is indeed baffling why too many of the otherwise intelligent and articulate are not – or are no longer – effectively supportive of the human rights framework; or why they can’t be convinced, as Chakrabarti puts it, of “putting up with irritation for the bigger picture and the longer view.”

In the longer term, we will need to do more to understand and win over at least some of the sceptics and the disinterested – which means moving on from focussing and analysing their deficiencies and transgressions. We need to find more effective ways to take on the powerful forces of shortsightedness, fear, complacency and indifference.

We also need to engage more robustly with those responsible for protecting the overriding human right – the right to life – against those who, whatever the experiences, indoctrination or provocation which brought them to this point, have little, if any, respect for that right.

For instance, many politicians would not be able to accept the Hoffman assertion that terrorist violence does not threaten the life of the nation – “our institutions of government or our existence as a civil community”, while nevertheless, at the same time, sharing his anxiety that “the real threat to the life of the nation . . . comes . . . from laws such as these”.

As Chakrabarti herself points out, realising our fundamental rights can involve a difficult – and delicate – balancing act. But that difficulty cannot result in dispensing with the rights framework. Once we do that, we are on a very slippery slope – to an uglier society and more dangerous world.

To conclude, this book should definitely appeal to any reader of Fabian Review and people of similar outlook: but we would suggest a sequel – sooner rather than later – on how we can rebuild a wider constituency in support of the UK’s longstanding core values.

Frank Judd is Labour member of the House of Lords, former Chair of the Fabian Society, former FCO Minister of State, and former Director of Oxfam UK

Nicole Piché is Co-ordinator/Legal Advisor, All-Party Parliamentary Human Rights Group

A shorter version of this piece originally appeared in the Winter edition of the Fabian Review