The iron lady generation

The millennials are the true heirs of Thatcher and we need to harness their drive in the progressive cause, argues Michael Weatherburn.

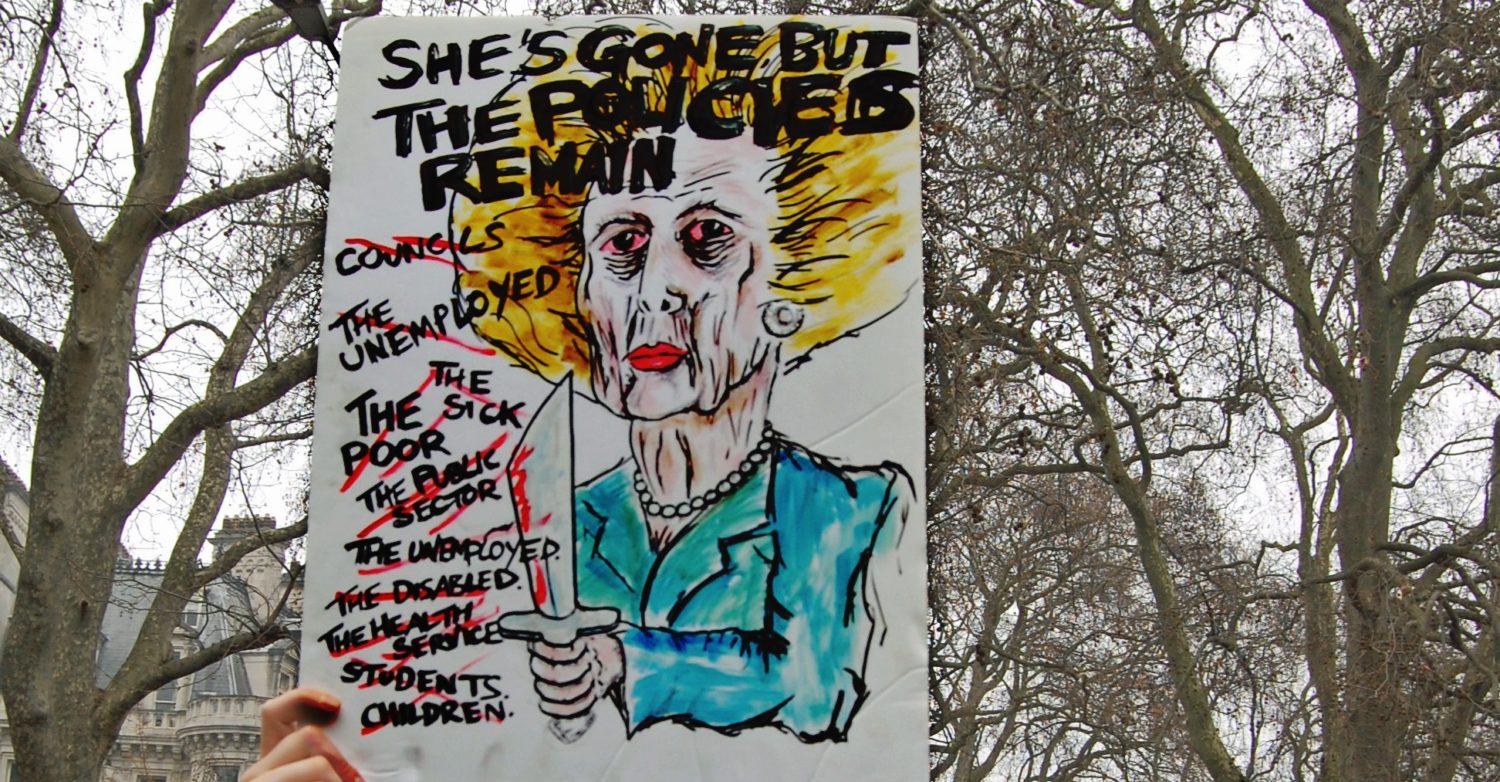

The term ‘Thatcher’s children’ has most often been used to refer to the generation born in the later 1960s and 1970s, otherwise known as Generation X. They came of age in the 1980s, and, living through the Falklands War and the miners’ strike, were deeply marked by Thatcher’s governance style and industrial policies. For those from working class backgrounds, their families may have become homeowners for the first time. For everyone, the country in which ‘there is no such thing as society’ left its mark.

These deep memories last, even scar, to this day. New Yorker writer Rebecca Mead, for example, recalled unexpectedly meeting her nemesis at a yacht party years after Thatcher had left office. She remembered how Thatcher unexpectedly ”drew within a foot or two of where we were standing. Perhaps it was the effect of the champagne, but I felt an impulse to throw myself at her feet – to tell her that she had made me, had made all of us who had spent half our lives under her domination. Instead, I stood silent, more dumbfounded than I have ever been before or since, until she moved smilingly on to the next guest.”

Watching the biographical movie The Iron Lady, one is struck by the young Thatcher, then Margaret Roberts, who remarks early on that: ”One’s life must matter, Denis. Beyond all the cooking and the cleaning and the children. One’s life must mean more than that. I cannot die washing up a teacup! I mean it, Denis. Say you understand.”

This singular phrase – that ‘one’s life must matter’ – could make us reappraise who we mean by Thatcher’s children. If we view the generational divide through this lens of a life which matters, surely the true children of Thatcher are not those who came of age in the 1980s but those who were born in the 1980s and grew up in the 1990s and early 2000s. In short, the millennial generation. During this period, hundreds of thousands of people were told that the ultimate goal was to ‘make a difference’.

These children of Thatcher – or millennials, or Gen Y – have attracted substantial attention from journalists, policymakers, academics, and business commentators in recent years. Now in their mid-20s to mid-30s, they are starting to enter into positions of influence and responsibility in many walks of life. And what has really captured so much attention is their approach to the workplace. Charlie Caruso’s Understanding Y argues that while millennials have a reputation for fickleness and 18-month employment spans, they are actually hugely results-focused. ”While other generations have been sold the story on job security, we’ve been brought up in an ever-changing world that values bravado,” Caruso and her co-authors write. These days, they argue, to win millennials over, ‘the focus must be on capacity and results. Gen Y is eager to deliver’.

Famously, having been brought up in the ‘politics-is-uncool’ 1990s, these Thatcher’s children have not been particularly politicised until recently. They voted Labour, or for the Cameroon Conservatives, or Lib Dem, or Green. Or not at all. One millennial, born in 1984, recently told me that she doesn’t vote as the ‘global north is more powerful than the global south so my energies are better focused there’ and anyway, ‘my parents’ generation have more experience with politics than I have’.

Yet this scenario changed dramatically two years ago. The one largely unexpected event which had the power to jolt Thatcher’s children into life was the result of the European Union referendum on 24 June 2016. Most of Thatcher’s children are horrified by not only the result but the direction of travel after it. Thatcher – despite her famous condemnations of a number of European leaders – played a huge role in European integration and the single market. And like Thatcher, the millennials see Britain’s future firmly within the European Union. Unlike, say, UKIP’s Nigel Farage, who left the Conservative Party after John Major signed the Maastricht Treaty in 1992, Thatcher’s children have little interest in the nation state, or blue passports, or the specificities of legislative process, or the House of Lords (or frankly the House of Commons). What the old-right is trying to resuscitate in its vision of a post-Brexit Britain are just the things that Thatcher’s children would like to dispatch with altogether. This is one reason for the deeply polarising nature of current political debate.

While nobody doubts that Thatcher’s children want to, and probably do make a difference in campaigns they support, there is a problem engaging them in politics, particularly that of a progressivist hue. They focus on causes close to their hearts and personally-defined outcomes rather than faraway parliamentary politics where others control the agenda. While she was a dyed-in-the-wool individualist, both Thatcher and the neoliberals who so powerfully influenced her realised that collectivism of one kind or another is the only force which wins elections. It is therefore from collectivism which we derive political, moral and legal authority to get things done.

But generally speaking millennials are not collectivists. Unlike Thatcher herself and Generation X (and perhaps ‘Gen Z’ – more on this later), Thatcher’s children look at large, structured organisations, including the nation state, askance. As some researchers have been revealing, the relation between Thatcher’s children and attitudes to authority, especially workplace authority and the centrality of the work-place to life, is one of the most fascinating sociological questions of our time. But it also impinges on our ability to tap this highly motivated, skilled, idealistic group of people to create collectivist change.

As Understanding Y observes, Thatcher’s children are goal-orientated and like to innovate both with products (ie outcomes) but also processes (ie management structures and the organisation of work). They unconsciously view government and the state as a kind of creaking bureaucratic megacorp of old, soon to be replaced by nimbler, more authentic start-ups. If we want to fix poverty, say, then why wait for the glacial speed of legislation, which can demonstrably be undone by future governments, when we can directly intervene right now by creating a bespoke charity or social enterprise?

In the world of businesses – charities, even – speedy in-tervention is certainly a very real possibility. But in relation to the state, and particularly the legal system (which ‘small-state’ Thatcher used to great effect), one cannot innovate with new processes when the state is the one entity which defines what processes count or even exist. And to refashion the state and its processes one has to be in a government.

As Georgia Gould put it in Wasted, the long-term decline of young people’s engagement with formal, national politics has created a relative strengthening of the influence of the older vote. Suspicion of the hostile nature of centralised politics, in part created by the hangover of the Thatcher period, is no doubt a powerful driver here. But as Gould also points out, younger people do care about matters which affect their daily lives, hence the high younger voter turnout at in the 2014 Scottish referendum and the keen focus on localism, particularly in England; the least devolved part of the UK.

To conclude, a note to any of Thatcher’s millennial children who may be reading. The literature has sometimes been harsh but at least you’ve been a key focus of debate. The focus is shifting to your younger cousins, ‘Gen Z’, who have been graduating from university for the past three years, and, who, having been raised in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis, are more likely to seek stable employment than Gen Y. And as Oscar Wilde once said: ‘There is only one thing in life worse than being talked about, and that is not being talked about’. This is a crucial period in British political history, and history more generally, and the best way to make a difference right now is to get involved in collectivist projects. To return to Thatcher’s quote. One’s life must matter, yes, but one must also agree that: together, we are stronger.