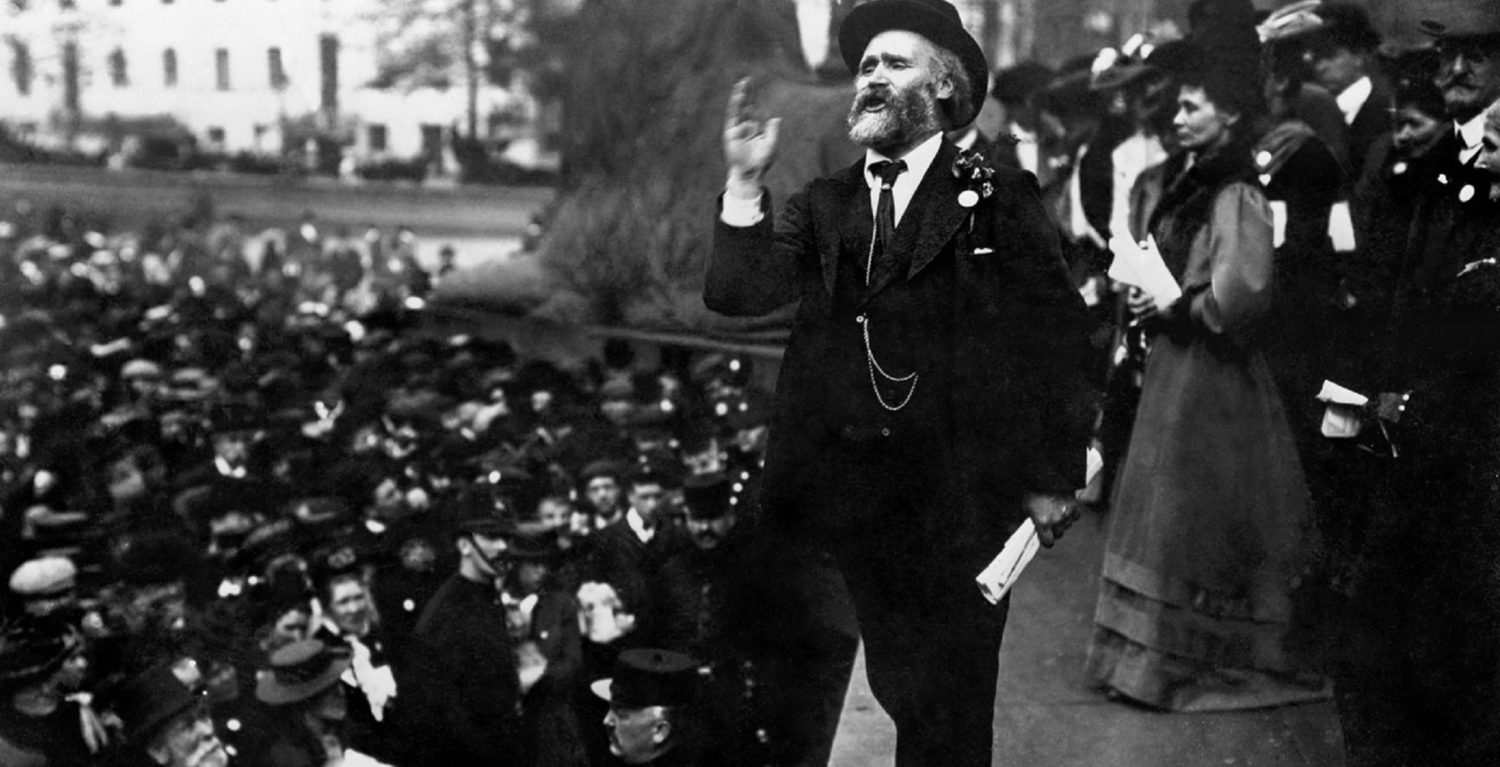

The people’s champion

Keir Hardie played a towering role in the foundation of the Labour party. Pauline Bryan explores what his story can tell us today.

The independent labour Party (ILP) and the Fabian Society were both involved in the founding meeting of the Labour Representation Committee (LRC) in 1900. With the attendance of the Social Democratic Federation and some trade unions, every strand within the movement was represented in what marked the birth of the modern Labour party.

The LRC was the culmination of years of campaigning led by Keir Hardie to persuade the trade unions to support an independent Labour party, rather than rely on a few trade union members being selected as Liberal candidates to represent working people.

By 1906 when the title ‘the Labour party’ was adopted, the role of activists from the ILP tradition was vital to its success. The founding meeting took place in Bradford rather than London in recognition of the activist base in the north of England. The Taff Vale judgement of 1901 – which essentially made strikes impossible – had encouraged more unions to become involved and the link with the trade union movement was recognised as central to the new party’s future.

For the first 30 years of its existence, the leaders of the Labour party were manual workers, with little formal education but often great orators. This, you could say, was the ILP influence. From 1935, the elected party leaders have been more in the Fabian mould with all but three of them graduates of Oxbridge or ancient Scottish universities.

Hardie is often nowadays presented in a sentimental way and photos usually portray him as an old man with sad eyes. His speeches and writing show that his own experiences had made him sensitive to the misery of the lives of many women and children and the damage done to the lives of men, but his main emotion wasn’t sadness – it was anger.

For many years his was a lone voice in the House of Commons. He was surrounded by people who despised him and all he stood for. He probably had the least formal education of anyone in the House; he had at first no parliamentary party to support him, yet he had the courage to stand alone and to rebuke the other members for their callousness and sycophancy.

His speeches, whether about mining disasters, unemployment, the oppression of working people, the rights of children or women’s suffrage, were often accompanied by boos and catcalls from the Tory and Liberal benches – and sometimes even from his own.

He described the House of Commons ‘as a place which I remember with a haunting horror’. Yet he knew he had to take the fight there, even though he was more at ease campaigning in the country, travelling across the globe and writing his column for children in the Labour Leader newspaper.

Keir Hardie’s place in history is well known, but what is his relevance to the present day? I would argue that Hardie’s experience and his writings have much to tell us in every area where people are in struggle. Hardie spoke directly to young people and encouraged them to have a voice in politics. He would recognise the campaigning zeal of climate change activists and welcome school-age kids into the movement.

His own earliest involvement in the Labour movement was as a trade union activist which resulted in him and his brothers being blacklisted from work in the Scottish mines. Zero-hours contracts and the gig economy are the daily experience of many working people and are not that different from the insecurity in Hardie’s day when the master hired workers on a daily basis at the factory or dock gate.

Local government was a central struggle at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century. In the early years of the ILP when many women, who had no voice in parliament, devoted their energies to winning improvements through councils, school boards and local welfare committees, Hardie campaigned for municipal socialism. It is an idea that needs rediscovering, as local government in the 21st century has sadly lost much of its radicalism. But there is a glimmer of hope coming out of Preston where the ‘Preston model’ is using local government to revive the local economy. It is Hardie’s municipal socialism in action today.

One issue close to my heart is Hardie’s opposition to an unelected House of Lords. In his 1910 election manifesto he said: “I would rather End than Mend the Lords”. He would be shocked to see that it continues to this day and still contains a number of hereditary peers. The very least we in the 21st century should do is to end this undemocratic part of our legislature as soon as possible.

Hardie’s support for women’s suffrage is well known, as is his defence of the role of civil disobedience. He, along with Sylvia Pankhurst and other socialists, saw that the rights of women needed to go beyond securing the vote to include rights within marriage and in the workplace.

At a time when travel within Britain was hard enough, Hardie travelled extensively across Europe, the British empire and the United States. In Ireland he stood in solidarity with striking trade unionists. Though he had differences with Irish members of parliament who put nationalism above socialism, he did support the cause of Home Rule. After travelling in the empire, he began to support liberation struggles under the influence of Gandhi and others. It seems incredible that over 100 years ago he was part of a worldwide network that would put modern day socialist parties to shame. While in the US he linked up with Eugene Debs and encouraged him to recognise the link between industrial and political struggle that formed the basis of the Labour party. He had high hopes for socialism in the US and more than a century later it is good to see parts of the Democratic party becoming more radical.

Hardie was not a pacifist, but he did oppose what he saw as wars of capitalism. By the outbreak of the first world war in 1914 his great comrade the French socialist leader Jean Jaures had been assassinated and the Socialist International that he had helped build had begun to disintegrate. The British Labour party along with other European socialist parties supported their own governments rather than international peace. This put Hardie at odds with his own parliamentary party, although not with the ILP.

Hardie died in September 1915 while still an MP, but his death went unacknowledged by the House of Commons. No tribute was made. It was unlikely that he would have wanted one. In his maiden speech to the House of Commons in 1893, he had begun as he meant to go on. Avoiding the tradition of being non-controversial, his first act was to move an amendment to the Queen’s Speech which was considered the equivalent of a vote of no confidence in the government. His speech was about unemployment and he became known as ‘the member for the unemployed’, a title he was happy to bear.

A speech Jeremy Corbyn made in September 2018 would have sounded very familiar to followers of Hardie:

“Everywhere you look this government is failing: one million families using food banks, one million workers on zero-hours contracts, four million children in poverty, wages lower today than 10 years ago. On top of that, there’s the flawed and failing universal credit, disabled people risk losing their homes and vital support, children forced to use food banks and the prime minister wants to put two million more people onto this. The prime minister is not challenging the burning injustices in our society, she’s pouring petrol on the crisis.”

The Labour party has recruited thousands of new members in the past five years. In some local communities it has become a bit more like the ILP of the last century by involving itself in local campaigns and following the ILP’s goal of ‘making socialists’. Hardie’s legacy must not be reduced to his image on banners and badges. Instead we can learn from his ideas and values and use them to strengthen today’s growing labour movement.

Photo credit: Wikimedia