The real spirit of 1945: what Labour’s next leader should take from Attlee

As we approach the final stages of a Labour Party leadership contest which has often generated more heat than light, it is essential to consider the kind of vision a new leader could develop to secure victory in 2020 –...

As we approach the final stages of a Labour Party leadership contest which has often generated more heat than light, it is essential to consider the kind of vision a new leader could develop to secure victory in 2020 – a vision capable of both uniting the Parliamentary Labour Party and offering hope to the electorate.

One response is that the party must return to the centre ground. Blairites have been lining up to argue that the only way to win general elections is by being a centrist party, much as Labour was in 1997. This willfully ignores the fact that circumstances have drastically changed since the mid-nineties. Back then, it was pretty much a straight fight between Labour and the Conservatives – albeit with some support for the nationalist parties in Scotland and Wales and for the Liberal Democrats in parts of Britain – and, crucially, the economy was expanding. By 2020 voters will have experienced a prolonged period of austerity.

The inclusion of Jeremy Corbyn on the ballot paper has enabled the left-wing counterargument to be heard. Labour has moved too far to the right, they say, and the difference between Labour and the Tories has become unclear, causing Labour to lose support among those who would traditionally have voted for it. Corbyn claims that by moving to the left, Labour’s message will be clearer, and it will regain votes from former members and attract a new generation of supporters. Furthermore, they argue that there is clear public support for many of the things which Corbyn is advocating.

What is unclear is how the left will win back those voters who distrusted Labour on the economy. Particularly as all of the various tax rises earmarked by Corbyn are linked to specific spending pledges – the deficit would need to be reduced by growth alone. Printing money is likely to be inflationary. There is also the ongoing issue of how much support Corbyn would have among MPs, given his own tendency to rebel in the past.

So, neither a shift to the right or to the left would work. And adopting a position somewhere in the middle, as Miliband did, has already been rejected by the voters. 2020 will not be a case of ‘one more heave’ – we need to change the fundamentals.

The closest thing to a solution, I think, during the campaigns so far has been Andy Burnham’s rallying cry, to rediscover ‘the spirit of 1945’. He has argued that the Labour Party has become timid, and would be incapable today of introducing the radical reforms of the immediate post-war period. But, away from Ken Loach’s romanticism, what does this actually mean?

It would be a mistake to see Corbyn as the heir to ‘the spirit of 1945’. The left of the party had been in the ascendant in the 1930s following the formation of the National Government and during the Great Depression when Marxism seemed relevant. However, by 1945, the dominant ideas were those promoted by the moderates who argued for a Keynesian macroeconomic framework supported by an active industrial policy.

The 1945 manifesto was one capable of uniting the right and the left. It was only after the main planks of the manifesto were implemented that divisions between right and left opened up, as the right called for ‘consolidation’ and the left for ‘genuine socialism’.

For the hard left of the party, the 1945-51 government was more about managed capitalism, taking essentially loss-making industries into public ownership, failing to institute worker control, aligning too closely with the USA and pursuing the atomic bomb. The reality was that the government was not one that the left were happy with, as seen by Bevan’s resignation. The left may now herald this period as a major socialist advance, but that is not how it was seen at the time.

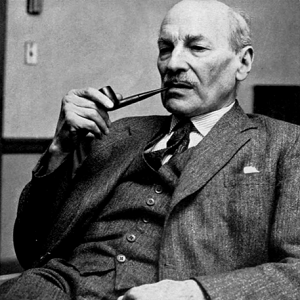

Instead, the Attlee government, and Attlee personally, are best understood as ‘centrist’ in terms of the Labour Party’s ideological spectrum. Not fundamentalist socialism nor capitalist amelioration, but a clear sense of optimism, with practical policies which would win support from both the party and the electorate. This period was far from idealistic – on the contrary, it was characterised by hard-headed and relevant policies capable of appealing to a broad cross-section of the population, more on patriotic than class lines at the end of the Second World War.

What we should take from this period, however, are the fundamental values those policies were rooted in: hope of a better future; the belief that an active state – central, regional and local – is essential for delivering social and economic progress; and that the good society is one underpinned by equality and social justice. The vision Labour articulates in 2020 needs to ensure that those values are championed once again.

In order to truly revive the spirit of 1945, Labour needs a policy framework capable of achieving the following:

- rebalancing of the economy – away from financial services to new forms of industry and away from the south east to the rest of the UK through a modern regional policy.

- reintegration of public services – with clear limits on marketisation and privatisation, the restoration of the comprehensive school principle whereby schools are not in direct competition with one another and serve the local community, and a national care service linking health and social care.

- responsible welfare – Labour should seek to restore the principle of universal social insurance, a welfare state which is there for everyone in times of need and which is based on the contributory principle.

- resurgence of a liberal national identity – Labour must recognise concerns on immigration and have a clear response. This involves measures to control borders but just as importantly ensuring that the wage rates of domestic labour are not undercut by immigrant labour and having an enforced higher minimum wage while actively encouraging a real living wage.

This would give substance to the idea that modern day Labour is about that sense of hope, and would allow the new leader a sufficiently bold message to both unite the party and offer the electorate a clear alternative to the Tories in five years time.

Kevin Hickson is writing in a personal capacity.