Where we want to be

They say that when you know you’re going to die, you don’t remember the deadlines or the car you had, you don’t wish you’d worked harder or saved more or eaten more fibre – you remember the kisses, the long...

They say that when you know you’re going to die, you don’t remember the deadlines or the car you had, you don’t wish you’d worked harder or saved more or eaten more fibre – you remember the kisses, the long sprawling days in the park with your friends, the people you loved and who loved you too. You remember the moments full of love, happiness, friendship and human spirit.

When we get a bank holiday many of us try and cram as many of these moments in as possible. A mad, scrabbling dash to live as much as possible in that extra day. As the sun went down on the first bank holiday of this month, the South Bank was peppered with the like. As the breezy, balmy hours drew to a close, people padded along the paves running along the Thames as it lapped at the pebbles. The walkways were awash with warm summer skin freckling and bodies hanging across railings with hands clasped around cups and cones.

The gentle whir of London continued, but at a different pace. The thick, warm air full of laughter and the natter of old friends catching up. Full of people spending time together – all sorts of people, lots of time.

As Marc Stears so elegantly put it in Everyday Democracy, “One of the last acts of Clement Attlee’s reforming Labour government was to transform an industrial wasteland in the heart of the city into a vast park for public entertainment as the centre of a Festival of Britain. Attlee’s Festival site was not just a super-charged fairground. It was the manifestation of an idea. The Festival was intended to present Britain as it should be. It was a practical example of what a free, orderly, generous, compassionate, and, most of all, democratic Britain would look and feel like.”

The way that people feel about the South Bank endures. It endures because it feels like it belongs to everyone. It endures because it feels like a free and peaceful place. It endures because the people who walk among it are the thing that make it feel special.

It’s a place where people really mix, and there aren’t all that many of them aside from the odd park and train. And if, like Stears suggests, we should be working towards a world and a society with more places to encounter one another, to find relationships that challenge us, then this is one such place to do so. It offers that most important of things – space where you can afford to enjoy being around people and being around culture. We need these spaces, to find and tie us to each other and to the communities around us.

Rising up out of the gentle stream of people bobbing along the bank, sits a tiny boat overlooking Queen Elizabeth Hall, perched atop a strip that flashes “Power to the people. Power to the people. Power to the people.” Just underneath, this bank holiday weekend past, was a small wooden table plastered with banners and sheets of petition paper, ready to tell anyone that would listen about the plans to redevelop this precious space.

http://youtu.be/HA5jkBwW6HM

“The history of the site always made me so excited, and still does.” says Southbank Centre art director Jude Kelly, fondly. “The Royal Festival Hall was created in 1971, after the second world war, when people were really thinking ‘How do we make the world better?’ And one of the ways to do that was to create a site that was dedicated to the idea of the people’s imagination”. While others involved in the redevelopment talk of the “festival philosophy” – which, they say, will be used to turn the current clutch of buildings and “relic of a great idea” into a new vision – many fear it will be surrounded by a wall of commercial outlets and more chain restaurants.

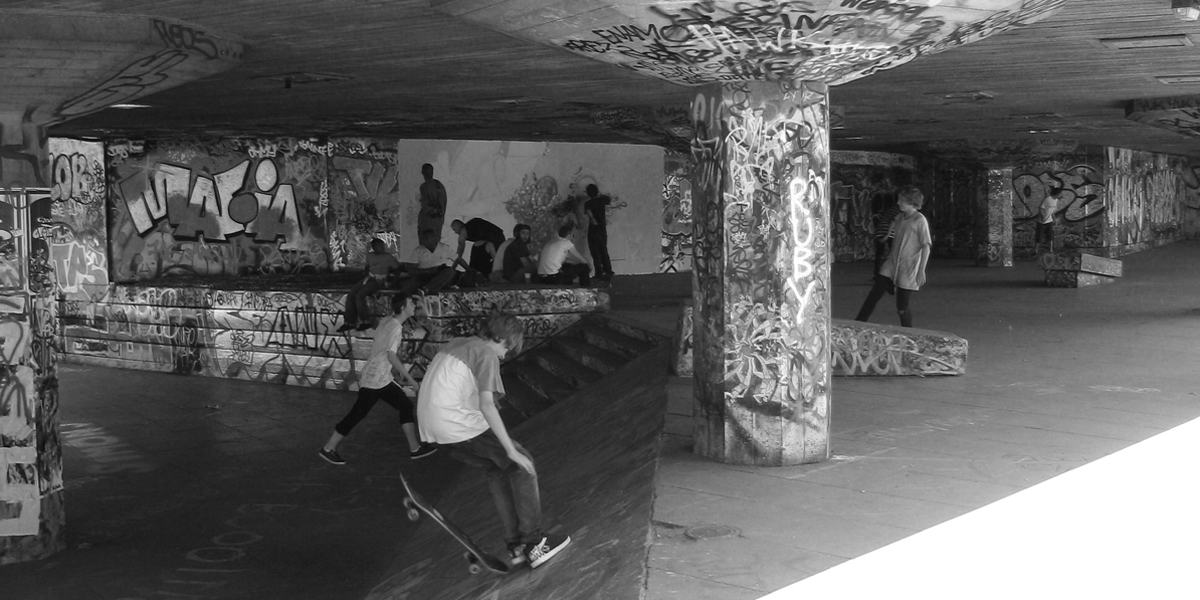

One of the most interesting and vibrant pockets on the South Bank is the skating undercroft, beneath Queen Elizabeth Hall. The current plans for the ‘Festival wing’ mean that this site would be redeveloped and the skating community relocated under Hungerford bridge. With the undercroft space key to securing the commercial backing needed for the project, the offer to the skating community is compromise rather than a stake, leaving them, in large part, understandably up in arms.

http://youtu.be/xJn5WOXbJOk

Long Live Southbank campaign spokesman Henry Edwards-Wood tries to put into words the history of the current skating space, when talking to Huck magazine, adding: “When there was no graffiti here it was magical, because it wasn’t about being next to all this art, it was about interpreting this amazing space that wasn’t designed for us and doing something different with it”. And you can see that differences, that merging of cultures – and the important and interesting questions is throws up: What is art? What is ‘urban art’? Is some art/culture more important than others?

There’s beauty in those differences and that is what the South Bank is about. The importance of this space for this community – the community that turn up day-in day-out, weather not permitting and use that space to find like minds and hone their skill. It means something because it is there – there for people to go to and for people to find – to create history and memories. Edwards-Wood touches on this too: “Public spaces in the city are going, y’know. And it’s not just about skate boarding it’s…places you can just walk around and be free and think about stuff and just be yourself, rather than being ‘go here, buy this, do that, conform’…there’s not many places like that left, so if this goes it’s going to be a sad day for the arts culture in England, not just for the skateboarders.”

Niall Neeson, founder of Kingpin magazine, has written recently that many, including him, are willing to see this redevelopment as an opportunity for the skating community, that keeps “the essence intact”. A chance for change, for renovation, for fresh starts and for new adventures. It’s with a sigh, it seems, that he gives into the fact that it basically comes down to money, whether it’s a high-level skate sponsor that steps in or the plan goes forward. But he talks of the history, of the reasons to fight and the reasons to win by not winning this time. “It is an article of faith in skating that despite our differences we all get into line in battles against the outside world”.

And there is a battle here, to retain something that’s important to so many, in a place where that always felt more valued. Neeson continues: “Nobody in authority really cares that much about ‘legitimacy’ or historical resonance of contemporary sub-cultures. That is because we don’t vote, basically. Hospitals and libraries are closing every day; convincing the outside world that it’s not up for negotiation – doesn’t seem to me enough to cut it today, I’m afraid.”

The skating community has now drawn a new line in the sand in this particular battle – using legislation designed for traditional means to stick up for their little slice of London and the historic resonance they feel the site has. An application to protect the space has been lodged Lambeth Council, using the Commons Act 2006, invoking laws usually used to protect village greens. If the spirit of the village green, a common space for all to spend time on hobbies and with each other, is alive and well anywhere today, it’s got to be the South Bank.

And here is where Stears’ Everyday Democracy takes hold, once more. Here’s the nub of it. Whether you think the South Bank is important and critical for the skating community or not, whether you think your local hospital is a key facility in your community or you want to support moves to redirect funding into local community care, whether you think everyone should be able to walk into a library in their part of the world and read a book for free – whatever you think about how you use these things, you have to make it known and talk to the community about it. We are people who use and care about these things, these spaces, these facilities. It’s time to use the power we have as a force, to be heard and talk to each other, to challenge each other, to forge the world the way we want and fight for our own little slice of wherever. “The NHS will last as long as there are folk left with the faith to fight for it” said Aneurin Bevan, knowing full well the power of our people.

But that’s the missing piece. The missing piece that Stears was talking about. And may very well be the thing on Ed Miliband’s mind as he clambers onto palettes up and down the high streets of Britain. It’s the missing piece to tie us together, for real, again – that democracy isn’t just in the voting booth. Democracy is out on the street and among the high rises if we look up and don’t like what we see. It’s scattered along the South Bank, between the old books and the strumming. It’s in what we want to fight for and how we work together to do so. It’s not in smashing or grabbing, it’s in talking, working and pushing ourselves forward.

“Our spirit of mutual responsibility is undermined by the transactional mindset…”, says Stears. And you can feel GDH Cole tugging at mutuality with dreams of self-governing as he looks out across the South Bank, Georg Simmel glancing at the chain restaurants and noting down how many more people exchange money than smile at one and other and the fleeting moments of the modernity that Zygmunt Bauman sees spraying out before us. The trouble with being human nowadays, Bauman suggests, is that we no longer give ourselves the time to be. And it’s easy to fall into that habit and relationships become something else. We become isolated and turn away from one and other.

Everyone has lost faith in politics, so they say. We’re told that we’re all so disengaged from and disinterested in politics. But are we really? There are voices speaking up and the change being realised in communities throughout the country through sheer will and collaboration. It’s not Westminster politics, it’s not anti-politics and it might not be neat poll-worthy politics or your definition of politics. But if we feel disconnected from the hands we put power in to, then the only thing to do is find hope in our own kind of politics. In the Name of Greatness, a short film by Dorothy Allen-Pickard, picks out that the spark of community in the grind of a day. “We can avoid another riot, if what we’re trying to build are real ties, to each other and to the present” spits Nicki Williams from her rainy backdrop. “To feel a sense of responsibility. To sympathise and empathise and criticise and recognise…a place. Where we want to spent our lives.”

We have to sit across a table from one and other and work out a way forward that works for as many of us as possible, and that keeps the magic in the places that we love. Because that’s everyday democracy of the sort that will help us piece together not a broken Britain, but one that has become divided and tough – a democracy where we can build and work and fight together for places and spaces and power. So we can carry on sitting with the sun on our faces next to a kid mesmerised by the waves on the Thames, as a young girl sits on a brick wall and sings towards a lady who covers her heart and says: “Aren’t you wonderful…..Eh, Graham! Can’t that lass sing. Isn’t she amazing.” And we all go home with more freckles and more smiles and more hope in each other.

If we want our voices heard we’ve got to sing. And maybe, like Kingpin’s Neeson says: “It never rains to suit everyone”, but surely by working together we can make sure that, at the very least, everyone has an umbrella.

Wouldn’t that be nice. Wouldn’t that be nicer.

You can find out more about how to support the Long Live Southbank campaign here.

Photo: Alexandra Mitchell