The unforgivable scandal

Millions of children are living in poverty. Labour must win the next election for their sake, argues Anna Turley

In the winter of 1947, my grandmother, with twin babies in her arms, was turned away from a London council welfare office empty handed after her request for some baby bottles that she desperately needed was refused. Although my grandad had just got back from fighting for his country, his job as a dustman was not enough for his young family to live on in one of the harshest winters on record. My nan was told that if she could not afford to look after her children, she should not have had them. One twin did not survive the winter, dying of malnutrition, so I never knew my Uncle Roy.

The development of a post-war social security net, just being put in place back then by the Attlee government, was supposed to mean that no child should suffer the ravages of poverty in a cold winter. Yet just recently, I heard testimonies from young mums visiting Hartlepool Baby Bank – a place to get vital baby supplies that many parents simply cannot afford – that brought home to me how thin and worn our social security safety net now is, and how perilously close we are to returning to those terrible times. I heard from families who are turning on their freezer for just an hour a day to try and save money, putting their health at risk, and of a mother who was delighted at the offer of a free dressing gown because it meant she would be warmer in a house where she dare not turn the heating on.

Through my work as chair of the North East Child Poverty Commission, I have heard hundreds of such stories: parents in Gateshead using watered-down evaporated milk in their babies’ bottles because of the soaring price of formula and putting off weaning because of the cost of solid food; parents in Newcastle turning down the offer of a free replacement boiler because they can’t afford to turn it on; children in Northumberland arriving at school exhausted because they don’t have a bed to sleep in; community groups in Redcar handing out slow cookers because people can’t afford to turn their ovens on. Families across the region are even ‘self-disconnecting’ from energy, despite still having to pay high standing charges.

Then there are stories like the child turning up to school in East Durham without any shoes, and a school in Middlesbrough which routinely buys shoes for its pupils out of its budget.

Stories of people in Gateshead unable to attend medical appointments because of travel costs, and, shockingly, parents in Sunderland terminating wanted pregnancies because they can’t afford the costs of a new baby. How hollow those words echo again today: “You shouldn’t have a child if you can’t afford it.” How can it be that in the sixth largest economy in the world we still have poverty of such magnitude that parents cannot afford to support their own child?

These cases may be shocking, but they are no longer extraordinary. There are now 3.9 million children living in poverty around the country and three quarters of those children are in working families. In the North East, child poverty has increased the fastest of any area in the UK, overtaking London to have the highest child poverty rates in the country, with 38 per cent of children now living in poverty. In some parts of the region it is even higher: 51 per cent across the Middlesbrough constituency, and nearly 70 per cent in the town’s Newport ward.

Child poverty is an acute tragedy, but the long-term effects are just as stark. Children who have lived in persistent poverty during their first seven years have cognitive development scores on average 20 per cent below those of children who have never experienced poverty. In 2015, 33 per cent of children receiving free school meals obtained five or more good GCSEs, compared with 61 per cent of other children.

In the most deprived areas, boys can expect to live 19 fewer years of their lives in ‘good’ health, and girls 20 fewer years, than children in the least deprived areas. Children living in overcrowded inadequate housing are more likely to contract meningitis and experience respiratory difficulties, and poor children are four times more likely to develop a mental health problem by the age of 11.

The crisis in child poverty we face is storing up a crisis in the health and wellbeing, educational attainment, employability and all-round life chances of Britain’s children. It is a scandal – for them, their families and for society.

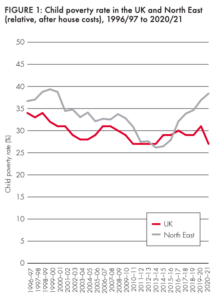

We know that child poverty is not inevitable. The last Labour government set out a twenty-year plan not just to reduce but to entirely end child poverty by 2020. By 2010, it was well on its way. This progress was driven by clearly defined policy action and political will right at the top of government. Figure 1 shows the impact policy decisions such as increased spending on benefits and tax credits had on child poverty across the country, and in particular in the North East, where child poverty was eventually brought below the national average.

An additional £18bn was spent on benefits for families with children under New Labour. But crucially, this was part of a wider package of ambitious policies, such as the national minimum wage, Sure Start, increased support for childcare, maternity and paternity pay and leave, and dramatic increases in spending on education.

A report by the IFS showed the overall distributional impact of tax and benefit changes under the last Labour government: the poorest 10 per cent of households saw an increase of 13 per cent in their incomes, while the richest 10 per cent lost almost 9 per cent. A million children were lifted out of poverty.

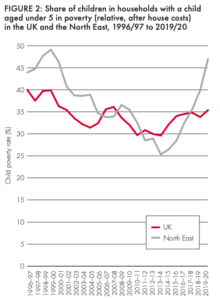

Yet how quickly this progress can be undone. Figure 2 shows a shocking rise in poverty for those families with a child under five in the North East – those who are most vulnerable and at the most crucial stage of their development. You can see poverty for these under-fives halved between 1999 and 2015 – from nearly 50 per cent to 25 per cent. Yet this progress has been reversed in half the time it took to achieve the reduction. This steep increase means there is now a 25-year high, and the gap between the North East and the rest of the country is as high as it has ever been for those children. But it also shows there is nothing inevitable about those families having to go to baby banks now. It does not have to be this way. As can be seen from the graphs, things have been getting worse for years, and the crisis these families now face is not simply because of the war in Ukraine or Covid-19, but because their financial resilience has been eroded over the years.

There are some immediate steps which could be taken to stop the crushing pressure on families. The government should look to raise social security entitlements with inflation, pause deductions from universal credit which are pushing families into destitution, lift the two-child limit and pause universal credit sanctions for families with children.

Over the longer term, the key challenge is to rebuild the social security system for families with children so that it provides a genuine, timely and dignified safety net. It is also vital that in-work poverty is addressed. We have seen a shocking 91 per cent increase in in-work poverty in the North East, far higher than the still significant increase of 27 per cent nationwide.

We need improved access to affordable childcare and early years education, and better support for those who are ‘economically inactive’. The North East has seen a larger rise in the number of families whose members are much less likely to be in a position to work, or who find it much harder to work without the right support in place, such as families where someone has a disability or families with a child under five.

We also need to take action to address high costs and poor quality housing for renters: 49 per cent of children in the North East are living in rented accommodation, with half in the private rental sector – the same private rented sector in which almost a third of the homes are below decent standard.

Millions of children across our country are suffering the devastating effects of poverty. We may have a new prime minister, but the last 12 years of Tory rule have left an indelible stain which no new leader can erase; a failing that is clear and undeniable and shaming and that has returned many to the post-war misery faced by my nan and so many like her. The re-emergence of child poverty is an unforgivable scandal – we must hold those responsible to account at the next election.

Image credit: Richard Cooke via Wikimedia Commons