Understanding Corbynmania

The labour party has much in common with the phoenix, the mythical, long-lived bird that is cyclically reborn. When the bird is in its youth, it is defined by beauty and power. As time passes, its feathers grow dull and it becomes tired. And...

The labour party has much in common with the phoenix, the mythical, long-lived bird that is cyclically reborn. When the bird is in its youth, it is defined by beauty and power. As time passes, its feathers grow dull and it becomes tired. And then, as it dies, it bursts into flames.

From the ashes of this leadership contest, a new party will be born. The nature of that party is not yet clear. But what precipitated the violent shock of Jeremy Corbyn’s election was a failure of tired ideas and tired politics. Labour must take this opportunity to rediscover its purpose. But before it can do that it needs to understand what has happened, and why.

Jeremy Corbyn’s meteoric rise has very little to do with the personal qualities of the man himself. Instead, his victory was a visceral reaction to four political and organisational challenges that the Labour party could, and should, have faced up to before now.

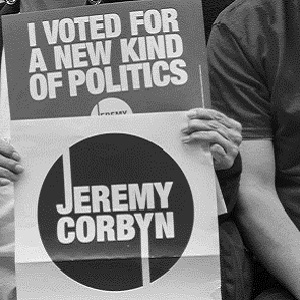

The first centres on an appetite for an end to ‘politics as usual’. In a world of suits and sound bites, Jeremy Corbyn cut through because he sounded and looked different. Just as Nigel Farage’s pronouncements awoke a populist right, Jeremy Corbyn’s ‘straight talking, honest politics’ grabbed the attention of the left. As one Fabian member and Labour councillor supporting Corbyn told me in an interview for this piece, Corbyn got his vote because he is “honest, forthright and sincere” and “an example to everyone”.

Analysis of Corbyn voters by YouGov reinforces this view. As a group they are much more likely to want to see ‘change’ and believe the world is run by a ‘secretive elite’. They are also almost twice as likely as supporters of the other candidates to have voted Liberal Democrat in 2010, the commonly accepted outlet for the ‘protest vote’ at that time.

Dissatisfaction with the political status quo has been building for years, with the effects of the expenses scandal still firmly embedded in the public psyche. You can almost feel people’s dislike of politicians when you knock on their doors, demonstrated most powerfully in Scotland as the SNP surged to power. Labour’s failure to react to the public mood for a new type of politics is part of the reason that Jeremy Corbyn captured such enthusiasm. He became the bearded and bedraggled face of a new political zeitgeist. A desire for politicians who say what they think and do what they say.

The second cause of ‘Corbynmania’ was the failure of the mainstream candidates, and the party at the last election, to articulate a new purpose for Labour in a vastly changed political and economic context. When I asked Corbyn supporters why they thought Labour lost in May, they overwhelmingly replied that it was because Labour ‘didn’t stand for anything’.

Jeremy Corbyn’s socialism is ideologically pure. It is easily understood, like New Labour was easily intelligible in the 1990s. But Ed Miliband’s Labour party was never really able to communicate what it stood for, despite a policy offer that was actually quite distinct from those of its rivals. The mainstream leadership candidates did little to demonstrate that they’d have done a better job.

Even Tony Blair has accepted that Labour must now change and apply its values to today’s context, and Jeremy Corbyn’s election surely underlines the conclusion of the 1994–2010 New Labour project. But if the party is to now reposition itself as a credible party of government then it must once again do what Tony Blair did. The Labour party was founded in the spirit of the workplace solidarity of the industrial revolution, but when it applied its values to a modern context, after the second world war, in the 1960s, and in the 1990s, it was able to change the country for the better. It must now find a way to apply those values to a post-crash, hi-tech, less hierarchical economy, while also facing up to an electorate less bound by traditional class or political party loyalty. Corbyn’s ‘old’ Labour is a denial of these challenges, rather than a solution.

The third reason for Jeremy Corbyn’s success centres on the frustration of powerlessness. When facing the reality of a further five years of Tory rule, voters in this leadership election prioritised ‘strong opposition’ over the compromise and discipline that comes with forging a government in waiting. The shock of election defeat in May has made many feel that Labour’s chances of returning to government are hopeless. When asked whether Jeremy Corbyn could win in 2020, one Fabian Labour councillor spoke for many when he said “I don’t really care”, “we need an opposition now.”

Throughout Labour’s history, the party’s left wing has tended to grow stronger in the years after the party leaves office. This makes sense. As regressive policies hit home, and as activists see people suffer, they embrace more radical ideas. It is a mistake to expect rational electoral strategy to triumph when people are reacting with anger and passion to what the Tories are doing and feeling powerless to stop it. One Corbyn supporter said “I’m voting for hope”. In this leadership election, the mainstream candidates failed to provide that.

Finally, there is an organisational point to make. The moderates were unaware of the threat of the left, and they were out-organised by them. One result of the Blair years was the hollowing out of Labour’s internal democracy. In the wake of Militant and heated rows on a national stage, it was deemed best to try and starve the malcontents of oxygen. While this helped with the presentation of a ‘new’ Labour party, it also meant the Labour leadership fell out of step with the membership. The hard left were controlled on a national stage, so their impact was underestimated elsewhere. That is perhaps part of the reason party leadership was prepared to facilitate left victories in some parliamentary selections, as part of wider deals with unions who were, themselves, struggling with an increasingly radical activist base.

Out of the view of head office, the organised left has been building at the grassroots. The strength of the Campaign for Labour Party Democracy is the best example of this. They have access to thousands of members through meticulous mailing lists, and the candidates they back regularly top the poll in the party’s internal National Executive Committee elections. In Young Labour elections, a new generation of left wingers challenge for national positions.

While the left of the party have been building, Labour’s mainstream has lazily relied on the strength of the party machine and the profile of the leader. It is not a coincidence that this summer the moderate candidates were swamped on social media by so called Corbynistas. They don’t have a gang to fight for them. Facing ‘movement politics’, they had only the strength of their argument. In politics, that is never enough.

Jeremy Corbyn didn’t win this election thanks to miscreant entryists, he won a majority among members and among legitimate Labour supporters. He didn’t win it because he’s personally charismatic. He didn’t even win it because Labour members suddenly surged to the left. He won because people were fed up with a tired status quo, and because Labour’s mainstream failed to organise and renew.

This leadership contest was the New Labour phoenix going up in flames. Labour must now be reborn from the ashes. Jeremy Corbyn knows what party he wants to build. The question is: does everybody else?