The power of fake news

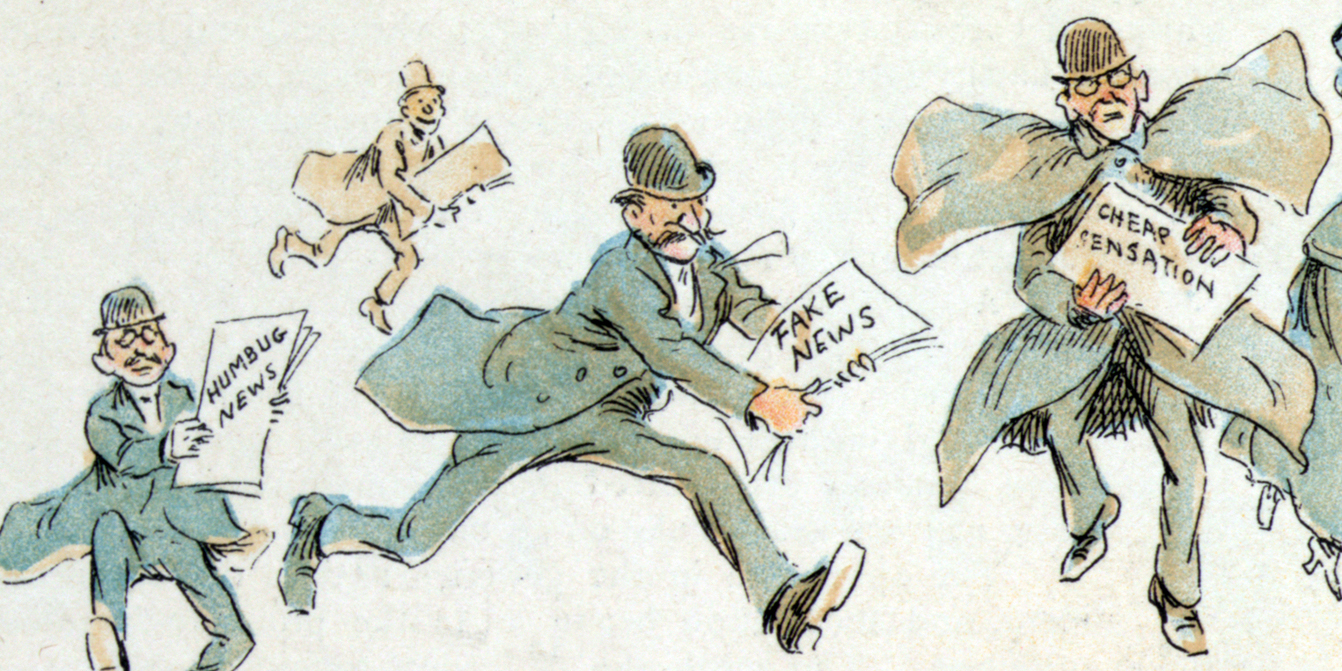

Political misinformation is of course nothing new but fake news in the Clinton v Trump contest came to mean something qualitatively different, writes Neil Serougi.

When will it end? The stream of ‘blow backs’ against mainstream facts demonstrates the powerful licence fake news has acquired in the media. It will no doubt get worse before it gets better. The re-emergence of global rivalries – using digital environments as a means of political shape shifting – has opened new and dangerous fault lines. This carries with it the potential to disrupt the ways we construct our ideas about political legitimacy. ‘Fake news’ is now pushed through a resurgent populist right wing agenda that invites its audience to do more than hear a different interpretation of ‘the facts’. Rather it invites a more visceral subscription to ‘rejection politics’ as a an act of emotional validation. It is of course the corollary of powerlessness and marginalisation and all the more difficult to resile without meaningful change to existing hierarchies of power and opportunity.

The emergence of fake news as a political concept began to gain traction amidst the US presidential election in 2016. Political misinformation is of course nothing new but fake news in the Clinton v Trump contest came to mean something qualitatively different. The latter exemplified its mendacious value by remorselessly berating the political electorate with a mantra sited on denials, denunciations and defamation. Crying ‘foul’ at a ‘rigged system’ wrought instinctual mistrust as a core value. Uncomfortable truths that might undermine Trump’s ‘dog whistle’ politics were dismissed as a surreptitious ‘establishment’ tactic to deny the American dream to those ‘left behind’. ‘Drain the Swamp’ became the antidote. It was undoubtedly a political success.

Recalibrating popular resentment by inviting voters to identify with Trump’s own narcissism had the impeccable hallmarks of a demagogue obfuscating his own corporate elite credentials. His language, narratives and confections, all cleverly reinforced the idea of mutual angst allowing political choice to become a cathartic moment as opposed to a logical differentiation. It’s quite conceivable that as a phenomenon, fake news was experienced by millions as a self-validating panacea; its real power not in what it said but the way it played into a dualism of powerlessness and projected fear. At one end the rage about national decline and lost prestige, at the other the pent-up anger of individuals struggling to reconcile under-achievement with poverty and diminished lives. For many, facts and truth was less important than metaphorically ‘giving two fingers’ to those they saw as responsible for fixing the odds against them.

Central to the idea of fake news is the question of delivery, particularly the exploitation of personalised technology to give the impression that ‘size matters’ more than authenticity. Authoritativeness is reinforced by the collective affirmation attached to the number of ‘visits’ and ‘likes’ whilst dissemination through retweets and sharing, imparts a pseudo legitimacy otherwise impossible. The virtual nature of its modus operandi reinforces this; vested interests are largely invisible providing a feeling of greater democratic equality for the user and a persuasiveness conferred by its apparent inclusiveness. Technology has certainly changed the landscape recalibrating the art of political deceit. One set of statements can enjoy parity of esteem with another irrespective of proof, provenance or control.

In the ‘make America great again’ mantra, alternative narratives about race, nation and community were revisited within a framework of establishment conspiracy. Distasteful and disingenuous in equal measure, this signalled the moment when a ‘post truth’ lexicon took root. The fact though, is ‘post truth’ – and the scale of the computational propaganda platforms which gave it its compelling potency – only partly explain Trump’s ascendancy. The empirical impact of big data exploitation may ultimately muddy the waters around cause and effect. Cambridge Analytics and Facebook’s surreptitious exploitation of data profiling and segmentation may have finally revealed the dangers inherent in new technologies through a big bang but culturally they merely followed a path well trodden by data scientists, psephologists and campaign managers.

To understand Trump we need to look beyond the omnipotence of technology whilst acknowledging its contribution and reject the idea that nothing at all was authentic about the ‘reaction’ to the state of the nation. It was and is too simplistic to suggest we are transitioning into a new dystopia predicated simply on unsuspecting populist susceptibilities allied to ubiquitous technologies. In this scenario, insurgent behaviours are reduced to the propensity for large sections of the population to passively accept distortion and lies amidst an inability to delineate between plausibility and gullibility. The determined efforts of the alt-right to target vulnerable populations amidst a digital ‘news’ presence replete with ideological shockwaves cannot fully explain the wide rejection of the political consensus that eventually occurred. The question of media influence is important but its traction is shaped by the material environment in which it functions. Economic conditions and social decline in an era of high wealth inequality and austerity did more to ignite anger.

The attraction of fake news grows on the dissonance between how people experience their lives and the dominant political prescriptions for the greater good and the national interest. Over a century ago, George Lukacs mused on the roles of ascribed and actual consciousness and the failure of marginalised classes to appreciate their ‘real’ needs. In the USA, fake news was effective because it operated in a way consistent with the idea of ascribed consciousness, acting on emotional as much as cognitive structures, cohering specific ideological notes about inequality and injustice into a seemingly common-sense explanation about causality, culpability and redemption.

Paradoxically these agendas, positioned around political themes cohered by a discourse of libertarianism, social conservatism and existential threats, foment popular discontent within an intelligibility entirely consistent with the neo-liberal policies responsible for the growing inequality and hardships in the first place.

The primacy of choice prevalent in other civic contexts also serves the pseudo-legitimation of this alternative media. Reflecting a paradigm where the ability to persuade a customer of the innate benefits of expressing a commodity preference is now normative civic behaviour, the act of searching and accessing alternative news outlets acquires merit by virtue of it being an act of market choice. The search for the ‘objective’ in news production in this context is replaced by the value of subjectively choosing from a range of alternatives. Culturally we have become accustomed to multiple choice so why not the news? It brings into question what we mean by reporting. Is anyone entitled in an age of choice and social media, to report the world as bona fide news? Is the impact greater now because social media merges the boundaries between feelings and observations, perhaps making it easier to ‘feel’ that truth equates to corroborative opinions corresponding to how we feel?

The terrain of what constitutes real, objective news is arguably fluid and at times messy. What we see as false is not necessarily the same as fraudulent and brings into focus what propaganda means. Where does the latter sit in an age when the means of news production has been proliferated beyond the control of formal media institutions. Is the impact the same? After all aren’t untruths still lies whatever their origin? Fake news ultimately amounts to more than propaganda but originates from the same pernicious motives – an attempt to create a climate for action that falls short of evidential justification. Perhaps a useful way to differentiate between propaganda associated with political advertising and fake news is to view them from the perspective of resonance and plausibility. With the former, we suspect its intentions and as such, for the most part, approach it with a cautious acknowledgement of its tendentious purpose.

Mostly we accept it for what it is; an ‘exaggeration’ for the ‘cause’, deployed with a sleight of hand designed to find greater favour for its core tenets. For some it’s still the ‘truth’ but with extra political attention to increasing the emotive impact on its audience. Of course, it’s a dangerously thin line to tread. History records how pursuit of ‘truth’ through propaganda frequently descended into systematic falsification and caricaturisation at the hands of authoritarian ideologues.

On the surface it should be easy to expose fake news for what it is. Its appeal should in theory be easily quelled by reference to facts and disclosure of the motives of its proponents. However, it’s clear that the appeal of fake news persists as a rallying call irrespective of proof. Here is the problem; we don’t necessarily speak what we see. We render our lives intelligible through complex relationships to the real world replete with ideological triggers about the reasons for our conditions.

The emergence of fake news as a powerful denominator in the political calculus about disempowerment and social justice invites an emotional response based more on a flag in the ground. It may contain falsehoods that are evidentially untrue and fundamentally erroneous but on another level, it has a character that acts as an ideological construction around resistance, identity and assertiveness. Invariably it encourages a civic authoritarianism that sees powerlessness as an array of grievances rooted in corrupt elites and the unfair elevation of the interests of the ‘other’. The conspiracies of misrepresentation and omission become the staple on which marginalised groups develop a didactic consciousness around their disadvantage. The power of fake news in this context is in its signification where its appeal is its ‘raised voice’ amidst the silence of a rigged system.

Feeling left out and left behind, the fake news syndrome offers a particular construction around participation and power irrespective of source reliability. As a conduit for anger and resentment, its danger lies not in its content but in its ability to cohere a reactionary inclusiveness for those consigned to watch from the margins.