A game plan for the left

Politicians are struggling to attract support in a nation where how you feel about Brexit matters more than anything else. Anand Menon believes there is a way of overcoming the tribalism.

I was chatting recently to a Brexit-supporting school friend who, apropos of nothing, declared that “Brexit is like football.” Prompted by me, he went on to explain. “Remember when Leeds were rubbish? And the only pleasure in life was watching Manchester United lose? Well … ”, and he smiled, counting the names off on his fingers, “Blair, Miliband, Clegg, Cameron, Osborne. We’ve pissed them all off, haven’t we?”

The story came back to me when pondering this article. Our country is profoundly divided, with faultlines as deep as those between fans of rival football clubs. The referendum of 2016 and its aftermath revealed a series of divisions which our electoral system had either blurred or prevented from clearly emerging. And they are numerous: between our various nations; between young and old; between rich and poor; between towns and cities. In addition, and perhaps most strikingly, the referendum seems to have generated another, deep and bitter divide, between leavers and remainers. This is hardly an ideal state of affairs. Equally, however, it provides opportunities for the centre left. And, unlike in sport, when it comes to politics there are ways of surpassing, or at least sidestepping, tribalism.

While the post-war era of British politics was defined by strong party loyalties, we have, since the 1970s, witnessed a marked decline in the numbers of people identifying with political parties. The evidence is there, visible in falling turnout, fewer people joining political parties and increased voter volatility. In 1970, 90 per cent of voters opted for Labour or the Conservatives and 98 per cent of MPs were aligned with one of the main parties. In the last election pre-referendum, these numbers had fallen to 67 per cent and 88 per cent respectively. The instinctive emotional connection with party politics appeared to be in terminal decline.

Subsequent to the referendum, however, there is strong evidence to suggest that new, Brexit-linked identities have emerged. Data from the British election panel study reveals that only 6 per cent of people did not identify with either leave or remain in mid-2018. Meanwhile, the percentage of people with no party identity increased from 18 per cent to 21.5 per cent between the start of the referendum campaign and mid 2018, by which point, while only one in 16 people did not have a Brexit identity, more than one in five had no party identity.

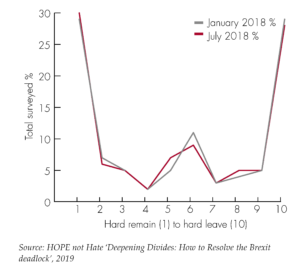

Recent research by HOPE not Hate, moreover, underlines that Brexit polarisation remains as stark, if not more so, than it was at the time of the referendum itself. There are few, if any, moderates in this game. Academics Miriam Sorace and Sara Hobolt have shown that leave voters are more eurosceptic now than they were pre-referendum while remain voters are now far more supportive of European integration. Politico, for its part, devoted a whole article to the phenomenon of the ‘Brexit anxiety disorder’ that has afflicted middle class remainers.

Partisanship, in turn, has spawned a polarisation redolent of the terraces. We have evidence from the London School of Economics and University of Oxford that while leavers and remainers attribute a series of positive characteristics to their own side (intelligent, open-minded, honest), they associate more negative ones (selfish, hypocritical, closed-minded) to the other. Indeed, only a third of those with a Brexit identity would be happy about a prospective son or daughter in-law from the other side. Some 11 per cent of remain voters say they would mind a lot, and 26 per cent would imagine a little, if one of their relatives was to marry a leave voter (I’d struggle with a Liverpool fan, to be honest).

Nor should we assume that the actual impact of Brexit will serve to bring people together. The research by Sorace and Hobolt has indicated that new Brexit identities have triggered biases in evaluations of the current state of the country. The long and the short of this is that leavers and remainers have distinct perceptions of the same economic and immigration reality.

Indeed, perhaps the only thing that unites people is dissatisfaction with the performance of politicians. HOPE not Hate found in their regular polling and focus groups that, while the referendum itself was profoundly divisive, the prime minister’s subsequent handling of Brexit has deepened those divisions. By January 2019, ComRes were discovering that only 6 per cent of respondents felt that parliament is emerging from Brexit in a good light, while 75 per cent felt that the current generation of politicians are not up to the task.

So what is to be done? In February, YouGov asked people what they thought would help fix the malaise that has taken over British politics: at 73 per cent – and the most popular answer by some distance – was MPs trying harder to work together to reach compromise in the national interest.

Fair enough, you may say. However, polling now consistently finds Theresa May’s compromise Brexit deal – and whether you like the contents of it or not, it bears all the hallmarks of a grudging compromise – is pretty unpopular. In other words, those hoping that some kind of Brexit compromise might do the trick and, as some people are fond of saying, ‘bring us back together,’ seem destined for disappointment.

It is also striking (though perhaps no surprise) that the main thing that could feasibly incentivise greater cross-party dialogue and cooperation on a permanent basis – a change in the electoral system – was way down the list of solutions that voters think might fix British politics. Even fewer thought a new political party is the best solution, so maybe it is not quite the popular cure-all that many of the breakaway MPs would like it to be.

Indeed, there are other reasons to suspect that the creation of political groupings intended to take advantage of the new divisions in our society is not likely to be effective. This is clearly the ambition of the newly created Independent Group of MPs, lacking anything approaching a viable policy offer, yet anxious at any opportunity to emphasise the clarity and centrality of their ‘values.’

Yet there are several problems inherent in this approach. In the first place, of course, are the problems inherent in launching a successful new party in a first past the post system in which the two large parties have achieved a dominance unparalleled in recent times (they have not between them garnered such a large vote share since the early 1970s). Second is the danger of emphasising a values divide that, as we have seen from American politics, may spiral out of control, and which threatens to under-mine debate about real policy alternatives addressing the precarious economic situation in which too many people find themselves.

Finally, on a very practical level, it is far from clear that the kind of pro-European social liberal approach propounded by the TIGgers is the most fertile ground for any new grouping. YouGov has examined the areas where the public feel least well represented by the major parties. Their findings suggest that leave voters are more likely than their remain equivalents to feel their views are unrepresented. Moreover, popular ideas that people felt have no resonance among existing parties include the notion that the justice system is not harsh enough and that immigration controls should be tighter – hardly Chuka Umunna’s pet projects.

So what should the left do? A clue is provided by the 2017 general election. Certainly we saw some perturbation because of the Brexit issue. Younger, educated, remain supporting voters plumped for Labour, while the Tories attracted older, more socially conservative voters and far more leave voters (73 per cent of 2015 UKIP voters voted Conservative in 2017).

Nevertheless, far from being simply a ‘Brexit election,’ the events of June 2017 revealed that classic left-right attitudes remained the primary driver of voter choice in Britain. And it is here that the left must focus. While all politicians are tainted with the brush of what the public see as a bungled Brexit process, there is an appetite, driven not least by what the referendum revealed, to address the drivers of discontent. This was true to such an extent that even the Tory party, via its newly elected prime minister and its 2017 manifesto, saw fit to challenge its own economic orthodoxies, and point to the numerous injustices that characterise the workings of British politics and the British economy. Jeremy Corbyn’s anti-austerity platform proved singularly popular, to the point of confounding pollsters and the political class alike.

This is a pointer to the kind of direction in which the left needs to go. Tory concessions aimed at winning support for May’s Brexit deal have rolled the pitch for policies targeted at less well-off communities and those labelled by the prime minister herself as the ‘just about managing.’ Public resentment at the failure of politicians has been engendered in part by the farce over Brexit, and in part too by the fact that a focus on Brexit has meant that parliament has done little or nothing to address the real problems confronting the country. The widening of the so-called ‘Overton window’, in other words, has created an open goal for the left.

The crowds that have ebbed and flowed around parliament, like fans immediately before the big match, are perhaps a symptom of something. But banner-wavers around College Green are so far from the cause of the current political crisis that they provide little indication of what we could actually do to solve it. Convincing people, whatever side they’re on, that politics is aiming to work in their interests would be a start, and the left is ideally placed to put forward policies designed to show just that.