A great example

Labour ministers should take inspiration from the career of Barbara Castle, suggests Niall Devitt

Picture a crowded tube platform in the autumn of 1940. It is the height of the Blitz. A young woman, with a head of striking red hair, is bending down to speak to a huddle of anxious shelterers, her soft Derbyshire accent contrasting sharply with the Cockney tones of those camping out for the night. Her name is Councillor Barbara Anne Betts, an Oxford graduate and Labour councillor since 1937 for St Pancras Metropolitan Council.

It is typical of her approach to politics to go and see first-hand the conditions in the makeshift shelters of the underground. In her own words: “Night after night, just before the sirens sounded, thousands trooped down in orderly fashion into the nearest underground station, taking their bedding with them, flasks of hot tea, snacks, radios, packs of cards and magazines. Without it, London life could not have carried on in the way it did.”

Councillor Betts is now better known as that true giant of the post-war parliamentary Labour party: Barbara Castle, the MP for Blackburn, one of the finest government ministers this nation has ever seen.

From her very first frontbench role as minister for transport in the new Wilson government, Castle made an impact. It is not an exaggeration to state that she may have saved what was left of the nation’s railways in the wake of the ‘Beeching Axe’ recommended by Dr Richard Beeching in the early 1960s. Much of the damage could not be halted – it is always difficult to reverse an avalanche in mid flow, especially when most of the civil servants, advisors and British Rail board think it a splendid idea. As in north London in 1940, however, Castle was deter- mined to find out for herself the conditions in the field. On a railway tour in north Wales, Castle turned to British Railway manager George Dow and exclaimed: “I can’t close them! Can you make it work?”

The seminal Transport Act of October 1968 offered a lifeline to the surviving branches. Very much the work of Castle, it acknowledged the existence of what was becoming known as the ‘social railway’ – loss-making branch lines that nevertheless provided social value, and which would require government subsidy to survive. Without Castle, there would be no trains to beautiful Looe in Cornwall; nor to faraway Mallaig on the romantic windswept coast of the West Highlands. In the latter case, Harry Potter would never have got to arrive at wizard school without Castle – the famed Hogwarts Express was filmed on this magnificent line. Today’s packed trains, including a regular steam powered service from Fort William, bear testimony to Castle’s wisdom and foresight. More broadly, by establishing regional passenger transport executives to help foster bus and train coordination, Castle had shown there was a real alternative to the car and that rail, buses and an extended underground network in London were worth the financial support required from central government.

Castle’s tenure also saw – despite green-inked death threats from motorists – the introduction of both the breathalyser and a permanent national speed limit of 70mph.

Castle was the first transport minister to fully grasp the implications of the Keynes-inspired concept of ‘cost benefit analysis,’ which could reveal the utility of projects that on a simple profit-and-loss basis would not be normally constructed. Against the backdrop of a looming devaluation crisis, in August 1967 she explained her thinking about the Victoria line to Brixton: “It will actually cost the board money. I have decided that the benefit of the line to the public, not least in relieving the congested conditions in which many of them have to travel, will outweigh any accounting loss. So I have given the go ahead.” Castle would push hard in Harold Wilson’s Cabinet and in debates for the ‘Fleet’ – later Jubilee – line to Charing Cross. Thirty years ahead of her time, she became an advocate for a congestion charge for London which could be then used to help subsidise the underground.

In sharp contrast to London Transport’s relatively enlightened policies stood the large parts of British Rail where there existed longstanding race bars, designed to prevent the recruitment of black and Asian members of staff. The situation came to a head in a landmark court case, the first successful prosecution under the Race Relations Act of 1965. Xavier Asquith was an experienced and exemplary employee, who, when applying for another guard position at Euston, was abruptly turned down. When he questioned the decision, he faced intimidation and even death threats. A furious Barbara Castle personally descended on Euston to force the British Rail board to end the now-illegal practice on the 15 July 1966.

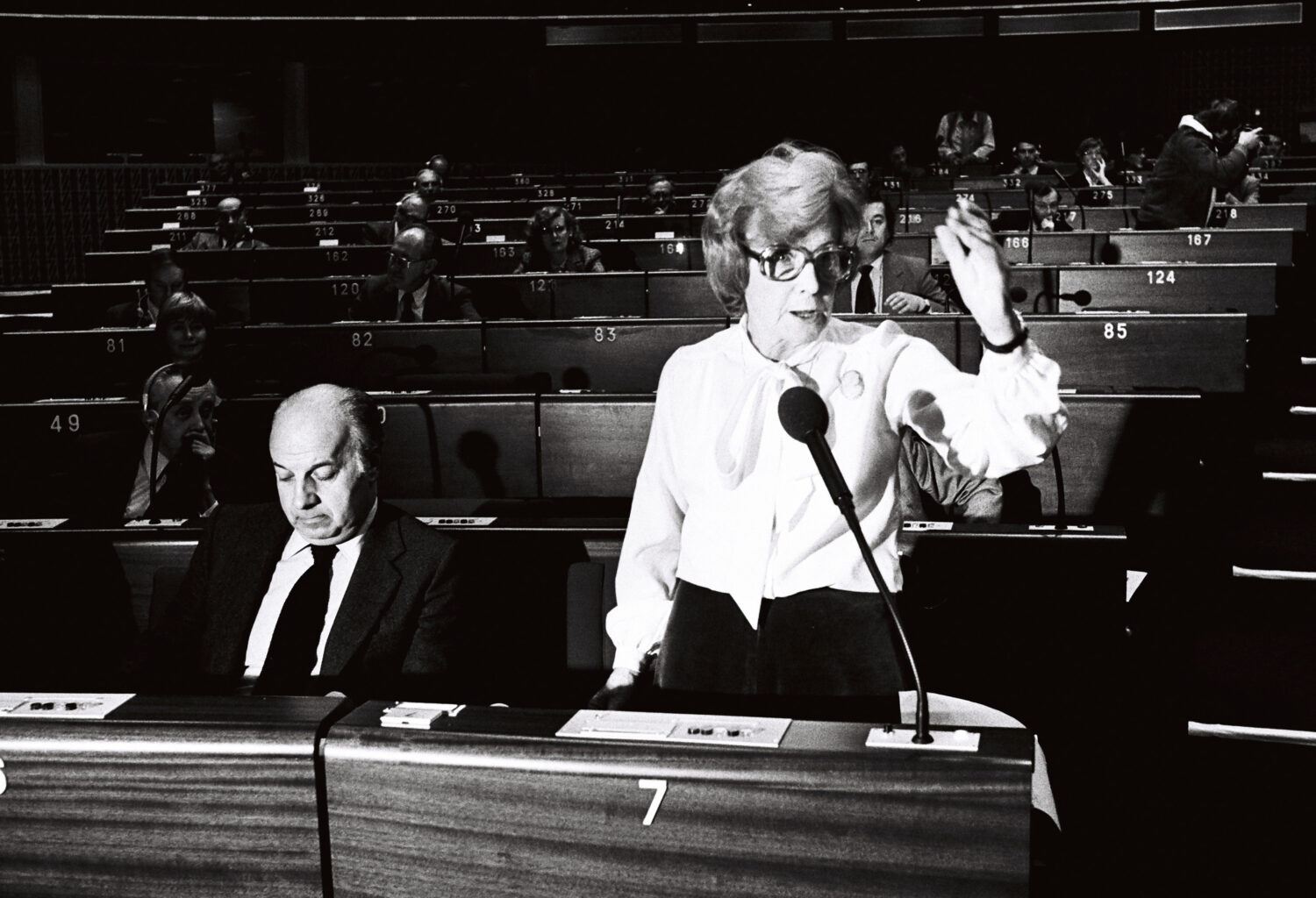

Ulla Lindstrom, Sucheta Kripalani, Barbara Castle, Cairine Wilson, and Eleanor Roosevelt (1949)

Castle’s tenure also saw – despite green-inked death threats from motorists – the introduction of both the breathalyser and a permanent national speed limit of 70mph. These policies alone have almost certainly saved countless lives since.

The Ministry of Transport had been a considerable challenge to sort out, a potentially poisoned chalice which she had handled with élan. Castle would need all of her considerable skill for her next mission as Secretary of State for Employment from April 1968. Wilson knew that the issue of industrial relations could make or break Labour governments. In particular, wildcat strikes, decisions taken with shows of hands rather than ballots, and openly communist leadership made trade unions, at times, the Achilles’ heel of the whole Labour movement and a gift to Conservative Central Office. Given her recent performance at the Ministry of Transport and her leftwing Bevanite credentials, Wilson, in secret talks with Castle, asked the new minister to draw up a White Paper to introduce what in hindsight seem an entirely sensible and reasonable set of proposals for reform. Delivered in January 1969, Castle proposed to force unions to call a ballot before a strike was held, along with the establishment of an Industrial Board to enforce settlements in industrial disputes. Famously titled In Place of Strife, her seminal work met with howls of protest from the so-called ‘brothers’, led by the Home Secretary, James Callaghan, and rising Labour stars including a young Neil Kinnock. (This proved to be a great irony, as both of their later careers would come to be defined by disastrous industrial action called without genuine ballots.)The defeat of Castle’s reforms laid the groundwork for the destruction of trade union power under successive Conservative administrations, leaving millions of workers vulnerable to unscrupulous employers, a situation that the new Starmer government will seek to belatedly remedy. Perhaps it would have been better for workers, and the country as a whole, if Labour had listened to Barbara in the first place?

Castle’s time back in the cabinet was to prove brief, with her nemesis in a still-resentful James Callaghan summarily sacking her on assuming the top job in April 1976. Callaghan claimed he wanted someone younger, and then promptly appointed an older male

Although Wilson was having to juggle a cabinet full of resentful Gaitskellites, many of whom would later leave to form the SDP, in hindsight, Castle had been badly let down, and Labour had just scored its greatest own goal of the post-war period. Though bruised, Castle would still secure the Equal Pay Act of 1970, enshrining equal pay, in theory at least, for working women.

With Labour unexpectedly returned to power in the two general elections of February and October 1974, Castle became Secretary of State for Health and Social Services. Another difficult portfolio even at the best of times, she managed to get through a series of radical reforms despite the party’s wafer-thin majority. These included such landmarks as Mobility Allowances and Invalid Care Allowance for single women and those who care full time for disabled relatives. Further, there were significant reforms to child benefits in the seminal Child Benefit Act of 1976, which ensured the firstborn child was included in addition to subsequent offspring, while significantly payments were to be made directly to mothers, not fathers. (Castle had remembered the sage advice of that other extraordinary Labour woman, Liverpudlian Bessie Braddock, the MP for Liverpool Exchange, who had warned that all too often it was the local pub landlord, not hungry children, who benefited from family allowances if they were paid to the man in the house.) Naturally, the last measure was fiercely opposed by male-dominated trade unions. In another significant change, benefit rises were linked to individual earnings rather than prices.

Perhaps Castle’s finest achievement was the monumental Sex Discrimination Act of 1975. Again hated by the unreconstructed, for the first time in British history, it enshrined the principle that women were equal in the workplace and would no longer be treated as semi-formed citizens liable to be discriminated against on grounds of sex or marital status. Though there is still a long way to go, especially with regard to pay disparities and promotion, the legislation had teeth in the form of the creation of the Equal Opportunities Commission (EOC). However, Castle’s time back in the cabinet was to prove brief, with her nemesis in a still-resentful James Callaghan summarily sacking her on assuming the top job in April 1976. Callaghan claimed he wanted someone younger, and then promptly appointed an older male minister in David Ennals MP. Not a good look, and hardly in keeping with the spirit of Castle’s act of the previous year.

What were the keys to Castle’s success? First, she knew how to talk to people, from permanent secretaries to the doorman and charlady.

To survey the battering she had to endure in the press throughout her time in office is to find a torrent of blatant misogyny, along with sly comments about her ‘fiery’ nature, striking red hair and taste for well-cut expensive French styling. No male minister would ever have to put up with this, though few could match her ability, common sense, decency and – all-too rare among Wilson’s front- bench – sobriety. There is much that today’s female frontbench would no doubt recognise; a different set of rules, under which a single hair out of place or smudged lipstick is immediately leapt on by the media.

Even in Castle’s retirement, a Labour grandee found time to describe this genuine giant of British politics as obsessing over her personal appearance. The comments have not worn well. The proof is in the eating, as it were, and her record transformation is still firmly in place, helping to define modern Britain in a way very few post-war politicians of either hue can claim.

What were the keys to Castle’s success? First, she knew how to talk to people, from permanent secretaries to the doorman and charlady. No minister benefits when people are too uncomfortable or frightened to speak truth to power. People came to trust Castle and had her back.

Second, she understood the importance of going out and talking to the people on the ground. For example, Castle famously invited a delegation of 186 female car-seat machinists from Ford Dagenham to come and explain how she could help them in their claim for equal conditions to the men. The end result was the aforementioned Equal Pay Act of 1970. Labour’s recent approach to policy formulation has similarly sought to escape the Westminster and Whitehall bubble, and find out what people actually want. It works.

Castle meets John Tembo, Malawian Minister of Finance while serving as British Minister of Overseas Development. Image credit: National Archives of Malawi, CC BY-SA 4.0

Third, her attention to detail when framing legislation. The cobbled-together legislation of the last 14 years shows what happens when this is not an absolute priority. In contrast, Castle’s attention to detail meant little further legislation was subsequently required to plug unforeseen gaps. The legislation establishing the concept of the social railway is a good example of this, along with paying child benefits directly to mothers.

Fourth, her ability to get to the heart of the matter. Sometimes the problem is not what it seems. Castle was right to question the assumption that all British Rail managers were hell-bent on closing loss- making lines as claimed by Treasury mandarins. Today, though the dire service and financially extractive practices of private train operating companies hit the headlines, the more intractable problem may well be an industry which is all too often inward looking, backslapping and dominated by Network Rail. No doubt the formidable Louise Haigh, who has so owned the transport brief in opposition, will know how best to prise Network Rail’s dead hands off the controls of a new state-owned Great British Railways.

Castle was a precursor to today’s notably powerful government frontbench female phalanx of Cooper, Dodds, Haigh, Mahmood, Nandy, Phillipson, Powell, Rayner, Reeves, Reeves, and Stevens. They are at the heart of a Labour party back in power where it belongs, escaping the dire fate of being relegated to the status of a narcissistic, shouty and above all ineffective pressure group. Castle, no doubt, would thoroughly approve of their determination to change Britain for the better – as she did.

Featured image credit: Communauté Européenne