A new Beveridge

The coronavirus pandemic has exposed deep flaws in a social security system built for a different age. Now, more than ever, it is time to lay out a new vision for the future, writes David Coats.

Last november, before the world was transformed by the Covid-19 pandemic, the Fabian Society published Where Next? Reforming social security over the next 10 years, setting out the need for immediate repair work to undo the damage wrought by a decade of austerity. At the time the proposals looked ambitious, more radical than anything outlined in Labour’s 2019 general election manifesto and highly unlikely to be implemented until the Johnson government had been consigned to the dustbin of history. Today, the weaknesses of the welfare state have been laid bare, leading a rather right-wing Conservative government to take measures that are anything but.

Ministers have been quick to recognise that universal credit, the contributory element of jobseeker’s allowance and the pre-crisis arrangements for statutory sick pay are simply not equal to the scale of the current challenge. The upending of the world as we know it has proved the state, and the state alone, has the capacity to act and offer people the security they need in the face of the crisis. Government support is now seen as critical, not just for those on low incomes or at the margins of the labour market but for all citizens and for all businesses. The devotees of Friedrich Hayek and those who believe that public services are a burden on the ‘real economy’ have nothing useful to say in the face of these unprecedented events. Social democrats should take no pleasure in an unfolding global tragedy, but there is solace to be found, perhaps, in the reality that we are, philosophically and temperamentally, committed to the role of government in protecting people from social and economic risks. For 40 years or more, market fundamentalists have been telling us that the state is the enemy of liberty and prosperity. Boris Johnson and his colleagues have had no alternative but to respond to the crisis by taking actions that are wholly inconsistent with their fundamental beliefs.

It is premature to make predictions about the political environment in which we will find ourselves after the crisis, but it seems inconceivable that the pre-Covid-19 status quo can simply be restored. The railways have already been effectively renationalised, governments may take ownership stakes in airlines and other major industries, public borrowing is set to break all the supposed rules of fiscal prudence and the Bank of England will need to crank up the printing presses to provide the authorities with the resources they need. The fundamentals of capitalism, as we have known them for the last two and a half centuries, have been suspended for the duration.

Making the argument for a small state, low taxes, limited regulation, unconstrained markets and a minimal welfare safety net will be much harder once the crisis is over, not least because it is public institutions, the NHS and the social security system, that will bear most of the burden in keeping the nation safe, healthy and secure. There is at least a possibility that social democrats can, once again, successfully make the case for an active and enabling state, offering security and opportunity for all citizens in good times and effective protection in times of crisis.

Labour’s general election defeat now seems like ancient history, so remote from present preoccupations as to be essentially irrelevant. Living in lockdown offers ample opportunities to cultivate our gardens, but it also gives us time for reflection on our own successes and failures. No matter where one may be positioned on Labour’s ideological spectrum, enthusiastic Corbynistas and unrepentant Blairites alike agree that the achievements of the 1945 to 1951 Labour governments were heroic. Creating the welfare state stands as an enduring testament to the power of progressive politics in action. And yet it is sometimes the case that a partial account of our own history distorts our understanding of the present and clouds our ability to think clearly about the future.

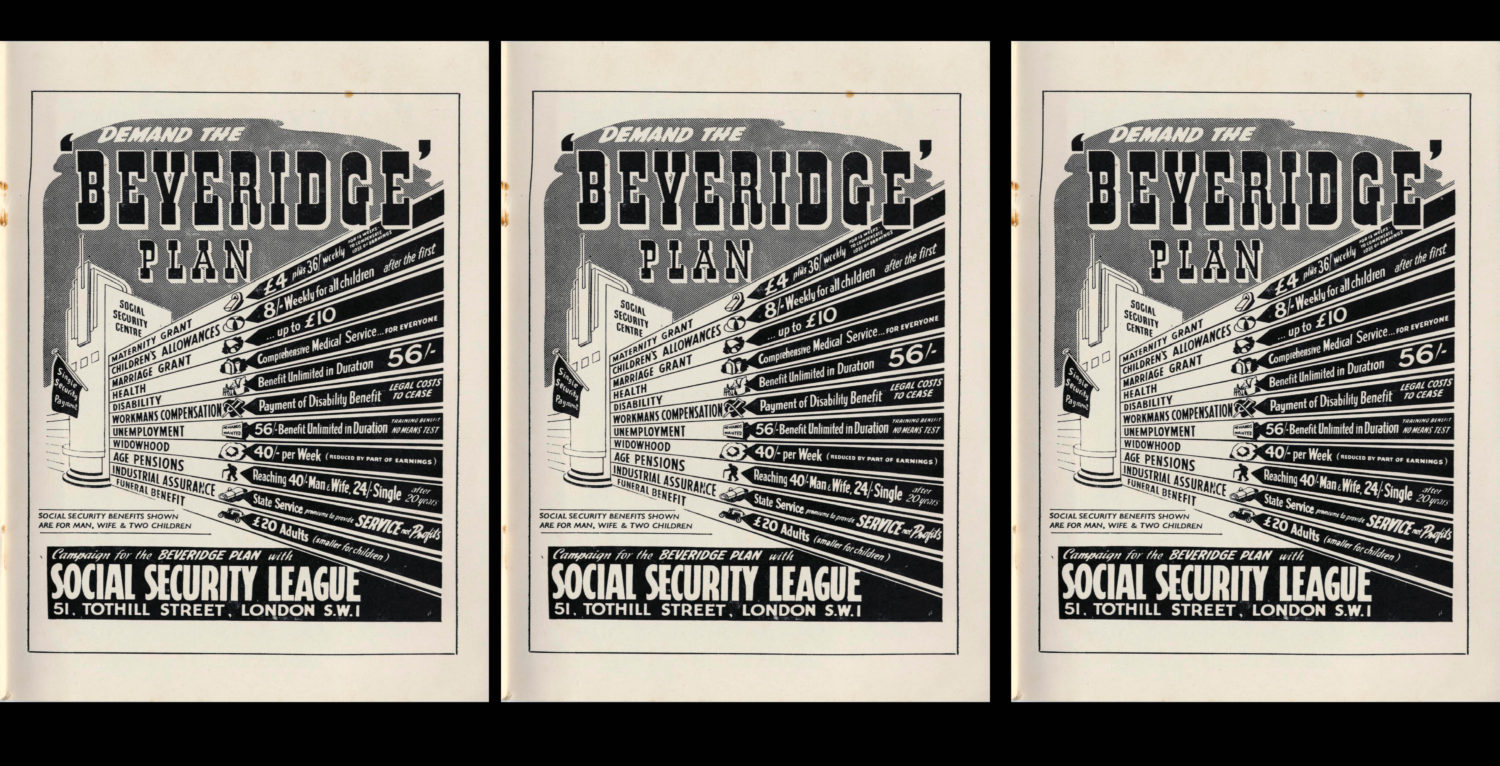

We should remember, for example, that the 1942 Beveridge report, which laid the foundations for the post-war settlement, was prepared by a Liberal academic, for a coalition government, led by a Conservative prime minister. Moreover, Labour’s commitment to full-employment, which was a critical departure from the policies of the 1930s, and was viewed at the time as a practical expression of democratic socialism, represented nothing more than the implementation of the 1944 white paper on employment policy, similarly endorsed by the wartime coalition.

Of course, it is right to say that the Conservative party was opposed to the creation of the NHS in the form it took under Labour, and there was some Tory hostility to the social security legislation enacted in 1946. But it would be wrong to conclude that the welfare state was inspired by either of the Labour party’s principal traditions – social democracy and democratic socialism. Both William Beveridge and John Maynard Keynes (who provided the intellectual foundations for the full employment policy) were trying to save capitalism from the destructive effects of unconstrained markets; they were certainly not trying to construct a new Jerusalem or a radically different social order. We might say that the 1945 to 1951 governments were successful precisely because they sought advice and guidance from within the Mandarinate and built on the success of the wartime coalition; there was broad agreement across political and policy making elites that these measures were essential for social justice and stable economic growth. Labour’s vision for the welfare state in 1945 was politically persuasive precisely because it was not a partisan programme.

Seventy-eight years after Beveridge we find ourselves in a rather curious position. The NHS remains the most popular and trusted institution in the UK – “the closest the British people have to a religion”, as Nigel Lawson once remarked with disapprobation. But the post-war social security settlement has fared less well. Beveridge’s proposals were for a system of social insurance, which built on the contributory principle that had been the lodestone of policymaking since Asquith’s Liberal government introduced a limited old age pension: “You pay in when you are working and take out when you are in need”. The word insurance was used advisedly, emphasising the point that the welfare state was (just like private insurance) a collective enterprise designed to manage risk. It was founded on the principle of reciprocity and recognised that individuals of differing means would never, in the absence of state intervention, be able effectively to cope with the vicissitudes of life to which we are all exposed – ill health, unemployment and old age.

The ideas of reciprocity and contribution remain embedded in the public mind today, but social security for adults of working age is almost entirely disconnected from the insurance principle. With the exception of the contributory element of jobseeker’s allowance, almost all benefits are means tested. In contrast to the NHS, the Department for Work and Pensions and Jobcentre Plus are more likely to inspire hostility than affection amongst citizens using their services. Again, unlike the NHS, the tight budgetary policies pursued since 2010 (the benefit cap and freezes, intrusive medical assessments for the disabled) have provoked a muted reaction from the electorate.

In the pre-Covid-19 period, protests by anti-poverty campaigners or advocacy groups (and Labour’s front bench) had no effect on either government policy or on the public mind. Certainly, there was anger about the number of homeless people on the streets and the growing use of food banks, but no connection was made between these phenomena and the coercive policies implemented since 2010. It is a testament to Labour’s relative political failure that ‘welfare’ was seen as a handout not a hand up; something of interest to the lazy, feckless and undeserving and a matter of indifference to the wider population. The Conservative party continued to see toughness in dealing with ‘claimants’ as a route to political success. In the absence of a more compelling political narrative, Labour was always going to be on the defensive.

This is a world that the architects of the welfare state would struggle to comprehend. Despite (or perhaps because of) their apparent radicalism, the 1942 proposals were popular, well-understood and subject to everyday discussion (in a way that the complexities of universal credit are not). Most public criticism was focused on the perceived inadequacy of the basic state pension rather than objections to social security and the welfare state. But, and this is the critical point, everybody had been through the war and had no desire to return to the pre-existing dispensation millions of people had experienced unemployment, poverty and economic disruption in the 1930s. The state had played the central role in successfully prosecuting the anti-fascist struggle and marshalling the nation’s resources in this endeavour. Government was trusted and had a proven capacity to combine bold ideas with effective action.

Covid-19 is changing the political rules of engagement in unexpected and unpredictable ways, just as was the case in the second world war. Policies that were condemned as lunatic or irresponsible only three months ago are now presented as necessities. Conservative politicians who have spent their lives railing against the power of the state are now presiding over the biggest expansion of state intervention in economic and social life that has ever been witnessed.

It would be easy in these circumstances to fall back on the cliché “we may have lost the 2019 election, but we won the argument”. After all, the Tories are implementing policies beyond Jeremy Corbyn’s wildest fantasies. But it would be quite wrong to believe that emergency action in a crisis inevitably lays the foundation for an enduring settlement. The rules of engagement may have changed but the outcome remains uncertain.

Relying on the proposals in Labour’s 2019 general election manifesto is a wholly inadequate response to a radical change in circumstances. The central proposal contained therein, that universal credit should be abandoned and replaced by “an alternative system that treats people with dignity and respect”, was completely silent as to what this new system might be and how it would work. Labour’s vision for the future of social security sounded more rhetorical than practical. It is all very well condemning the awfulness of universal credit (who could think otherwise?), but what precisely was Labour proposing to do? Where would the state act to provide insurance for citizens against social and economic risks? Where would the boundaries be drawn between universal benefits, contribution and means testing? What commitments were there to a continuous review of policy effectiveness to ensure that poverty and inequality were being reduced?

The last time the electorate embraced a vision for social security the language was grand and the ambition immense. Beveridge designed his proposals to ensure that the five giants of want, disease, ignorance, squalor and idleness would be eliminated forever. There was a keen appreciation of the challenges that many people faced in their lives and a commitment to decisive action.

Covid-19 has exposed the fragility of our economic and social arrangements. It has revealed the inadequacy of a social security system designed for a very different world. Keynes and Beveridge may have lived through the Spanish flu pandemic of 1918–19, but neither gave any thought to the impact of a public health threat on the life of the nation. Nor did they consider the likely upheavals consequent on climate change or the impact of digital technologies on settled patterns of life and work. If we want a social security system that is fit for the future, then we need a new Beveridge.

Institutions only endure if they are supported by consensus and that suggests there must be, as a first step, an impartial, dispassionate assessment of the risks to which citizens are exposed combined with a judicious account of the capacity of the state to offer worthwhile guarantees of security. As we learned in the post-war period, an ambitious, sustainable programme of (re)construction cannot be the preserve of one party alone. Working beyond party lines is always challenging, but there are examples of collaboration leading to practical and enduring changes in policy.

The Scottish Constitutional Convention, for example, established in 1989, played a central role in the development of the devolution settlement. It brought people together across the political spectrum and engaged civil society groups too (trade unions, churches, business representatives). Their blueprint, Scotland’s Parliament, Scotland’s Right, was published in 1995 and the structure of the Scottish parliament generally followed these recommendations.

The Social Justice Commission, created in 1992 following John Smith’s election as Labour leader, may look more obviously partisan, but its members included a future Liberal Democrat MP and representatives of faith groups with no obvious political affiliations. While the ambitions may have been more modest than the aspiration for a comprehensive Beveridge-style settlement, the Commission did lay the foundations for the 1997 to 2010 Labour government’s approach to active labour market programmes, education and training policies and the importance of work as a route out of poverty.

Perhaps what is needed is a hybrid of these two approaches – not as open as the Scottish Convention and not as ‘Labour’ as the Commission on Social Justice. Any new inquiry, following the example of Beveridge, should be led by a major public figure with the intellectual heft to manage technical and political complexity. And there must be an opportunity to engage with the public too, with formal evidence sessions, events across the nations and regions and, perhaps, the use of a citizens’ jury to consider policy options before final recommendations are made.

Labour’s recent experience has proved that simply attacking the government and making nebulous promises of radical change offers no path to victory. A world transformed by Covid-19 offers an opportunity to reassert the progressive case for evidence-based policy. A pandemic cannot be overcome by tweets, amusing after dinner speeches or dubious slogans on a bus. Social democracy is nothing if it is not rational and empirical, which explains why we have struggled in times when passion appears to trump reason and facts do not matter. Now is the time to reassert the core values of the Fabian Society. Expertise, patient investigation of the social realities and creative policy responses founded on a belief in the power of the state will be essential as we seek to build a resilient post-crisis settlement.