Abolish or reform?

We should tax private schools and remove their charity status, argues Patricia Walker.

The principal of one of Thomas’s London Day Schools – a private preparatory school group – whose pupils include a prince and a couple of princesses, recently expressed dismay at what he called ‘the mantra, I pay therefore I expect’ among the pushy mums and dads of his pupils.

Since the schools have been in his family for generations, it is astonishing that he has only just realised that his pupils’ parents shop around and are concerned about value for money. Surely those who choose to commodify education must expect that those who pay substantial sums for their goods and services, will behave as customers and want to make demands in exchange for hundreds and thousands of pounds spent.

School fees have risen by nearly 100 per cent since 2003, so it is surely to be expected that buyers want to see a return on all that cash. They presume their children will achieve and do better than the children down the road having ‘free’ education, though as we know it is not free but only free at the point of delivery, and paid for from taxation. Compulsory or state education is not a commodity to be bought and sold on the open market, it is a human right as declared in the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child ratified by 196 nations.

Yet those who are running our country are nine times more likely to have gone through the private school system than the general population. In 2019, two thirds of Boris Johnson’s cabinet are privately educated, the Sutton Trust calculates. That is twice as many as Theresa May appointed in 2016.

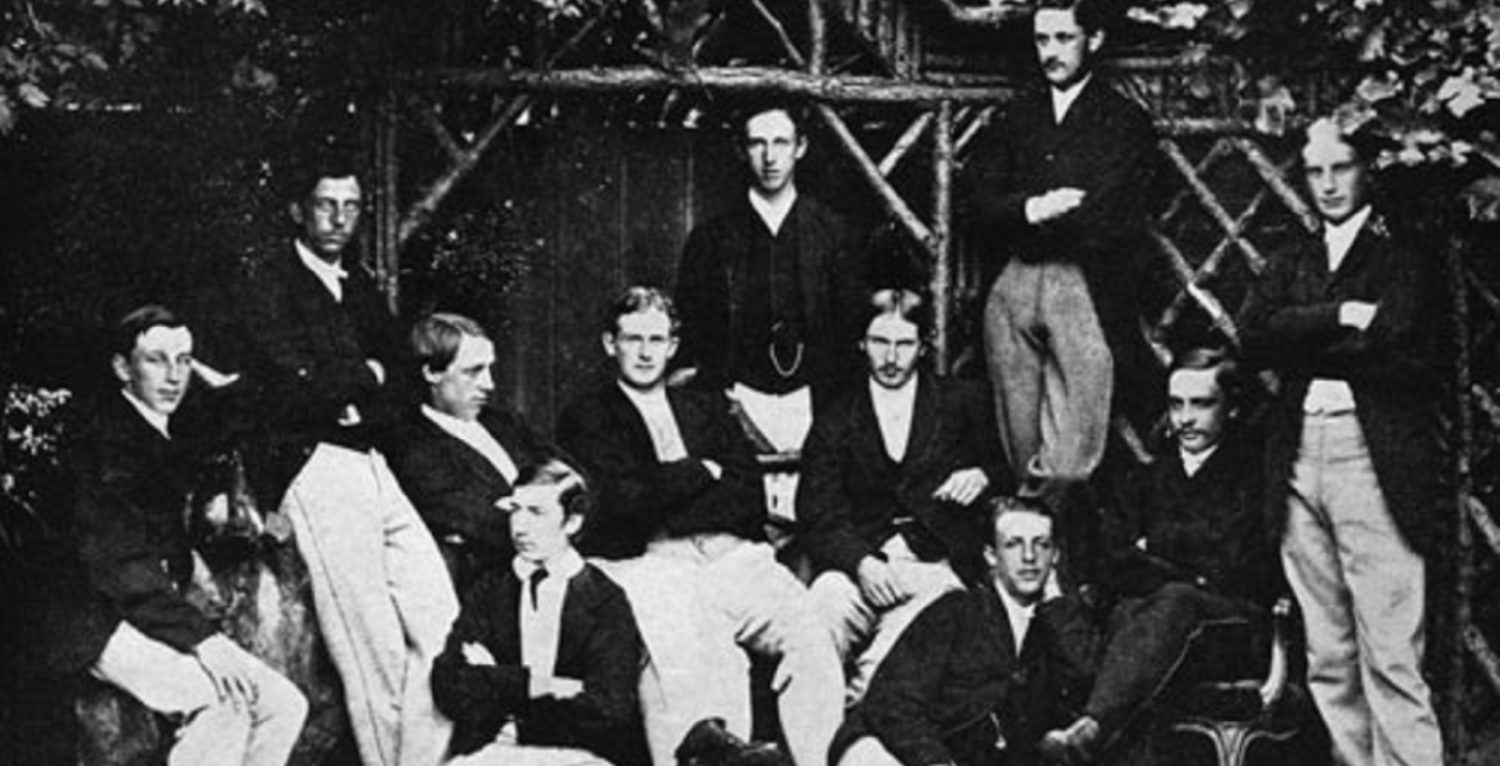

Old Etonians account for 20 former prime ministers. This is how we explain ‘elitist Britain’ or what David Lammy MP has called ‘entrenched privilege’. Is this an apartheid system of education and should these private schools exist at all? Opinions vary as to whether they should be abolished, as Jeremy Corbyn and Angela Rayner have advocated, viewing them as relics of a bygone age which should be swept away.

Others within the Labour party and elsewhere in the country are unwilling to support abolition out of respect for the schools’ revered origins. Some private schools go back to Saxon times such as the Cathedral schools, as they were known, such as that in Canterbury instituted by St Augustine in 597AD. Literature, language and respect for knowledge, was said to have flourished from the then recently established Christian faith. Schools therefore tended to be associated with and remained closely linked to religious institutions. Such schools, to which flocked the sons of the nobility and the establishment elite, emanated kudos and erudition: it is difficult to imagine these ancient and venerated buildings, grade listed in many cases, being repossessed as Rayner was advocating.

In the middle ages, charitable bequests were set up to educate the poor and the emerging lower-middle class so that children (mainly boys) could utilise their learning to lift themselves out of poverty. This notion however stimulated the expansion of schools in Victorian times leading to the introduction of fees. In the 20th century those schools charging fees decided to rebrand themselves as independent schools but kept their charity status.

At present, the UK is a mature democracy, operating – for better or worse – a mixed economy of state and private enterprises. Private schools are commercial operations existing alongside state education. They charge high fees for their goods and services. Something in the region of £6,000 a year for primary, £10,000 for secondary, £20,000 for boarders. The name is the brand, some more valuable than others – £40,000 for Eton, for instance. Parents are clients paying for the teachers’ expertise; or customers buying the products, the A levels, the Oxbridge entrance. Naturally they make demands of the purveyors, influencing- or not – the success of the end users – the pupils.

As a result of being registered with the charity commission, they can pay their cash into low risk investments and avoid capital gains tax. They soften their image by offering (small numbers of) bursaries or award a scholarship or two, but this is nothing but a marketing strategy, like ‘buy one get one free’ or ‘introduce a new customer and we’ll give you a better deal’.

Unlike private schools, all state schools are required to pay business rates rather than normal council tax. Their property is inspected from time to time, for instance by the local council to assess the current rateable value. That private schools do not pay business rates is a gross injustice, when charging these institutions business rates could bring in £1.64bn a year, according to a shadow treasury memo released in September 2019. Furthermore, charging private schools VAT would bring another £105m into the treasury.

Here is where the politicians’ axe should fall; remove their charitable status, tax their profits, let them perform as the businesses they truly are, and see if they survive – or not – as other businesses do, in the vagaries of the marketplace.

Photo credit: click here