Beyond tax and spend

We don’t need to have a perfect answer to Britain’s ‘productivity puzzle’ to see that a different approach is needed, argue Kate Bell and Geoff Tily.

The idea that tax and benefit system is not the only way to achieve fairness is now pretty embedded in politics. Whether you talk about ‘pre-distribution’, ‘new models of ownership’ or even a ‘National Living Wage’, politicians have signed up to the idea that how the economy works, as well as how the proceeds of economic growth are distributed, is important for the health of families’ living standards.

But when it comes to the health of the nation’s budget, tax and spend still dominates debate. Whether the sums will add up for the funding of individual policies rightly receives significant scrutiny – but the much bigger impact on the budget of the way the economy is working is often seen as something outside the scope of fiscal debate.

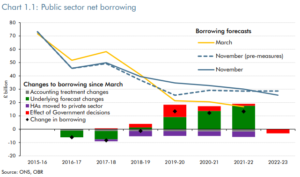

That’s worrying, when the impact of changes in economic growth has by far the largest impact on the public finances. The chart below, taken from the OBR’s November 2017 Economic and Fiscal Outlook shows that the impact of ‘forecast changes’ – in green – dwarfs that of government decisions – shown in red.

‘Forecast changes’ encompasses a range of issues – including new modelling by the OBR. But the most significant impact comes from the OBR’s estimates of productivity, and its impact on earnings. They state that: “By 2021-22, weaker earnings growth reduces receipts by £12.5 billion relative to our March forecast. This is the largest single contribution to the upward revision we have made to the budget deficit in 2021-22.” For a bit of context, it’s worth remembering that £12bn is the amount that George Osborne promised in 2015 to cut from the welfare budget – cuts resulting in a loss of over £1,000 a year for the poorest two tenths of families.

This isn’t to argue that politicians should replace explanations of how they intend to pay for future pledges with a vague promise that the economy will grow. But it is to point out that reversing our current weak investment, weak wages, weak tax-take cycle is by far the most important thing that government could do to improve the health of the public finances.

It’s also worth remembering that the past eight years – the period of the slowest wage growth since the Napoleonic wars – have been the result of policy that presumed the direction of causation ran the other way – from a balanced budget to a healthy economy. George Osborne, introducing his 2010 budget, argued that ‘the most urgent task facing this country is to implement an accelerated plan to reduce the deficit. Reducing the deficit is a necessary precondition for sustained economic growth. To continue with the existing fiscal plans would put the recovery at risk, given the scale of the challenge’ (emphasis added).

This so-called ‘expansionary fiscal austerity’ was meant to see private sector investment flood in to fill the gap left by public spending, leading to economic growth, and thus further reductions in the budget deficit, beyond those achieved by public spending cuts. We now can say pretty conclusively that that strategy didn’t work. Public sector debt was expected to peak at 70 per cent of GDP; it is now within touching distance of 90 per cent of GDP. Warned of five years of cuts to public services, households have now endured eight. The OBR show at least five years more to come, and there’s no commitment that even by 2022-23, if a Conservative chancellor is in place they won’t still be arguing for the need to tighten our belts.

Instead, Britain has been trapped in a low demand, low investment, low wage, low productivity cycle. The lack of government spending across public sector wages, services and investment has slowed growth, reducing incentives for the private sector to invest. And in Britain’s low wage labour market, the easiest option remains for companies to grow by recruiting more workers – rather than investing in technology to help increase the effectiveness with which workers can do their jobs.

We don’t need to have a perfect answer to Britain’s ‘productivity puzzle’ to see that a different approach is needed.

The present approach to ‘fiscal choices’ has meant serious neglect of the way these decisions impact on the economy. Eight years into austerity grave harm has been done to our public services and to the well-being of the workforce. And even on the government’s own terms, public debt has risen.

Even Philip Hammond has recognised the need for some additional investment – though the National Investment Fund is set to see UK public infrastructure expenditure reach just 2.8 per cent of GDP against the OECD average of 3.7 per cent and public services across the board are still struggling.

But we’re yet to see any recognition that Britain’s wage crisis is not only a disaster for individual working people but for the health of the public finances, and the public services they fund. ‘Wage led growth’ might be just about as catchy as pre-distribution as a slogan, but perhaps it too can work its way into the political debate.