Continental Partnership

The path to a soft Brexit lies along a very narrow ridge, with vertiginous drops to hard Brexit on one side and to remain on the other. Even worse, we’re groping along in the dark, with each step – a...

The path to a soft Brexit lies along a very narrow ridge, with vertiginous drops to hard Brexit on one side and to remain on the other. Even worse, we’re groping along in the dark, with each step – a Theresa May speech or a by-election result – sending some rocks clattering down the cliffs.

The particular nature of the Brexit vote is part of the reason there is so little middle ground. Immigration featured heavily in the referendum, yet the actual democratic mandate is to leave the European Union and nothing else. There are Brexit options, such as membership of the European Economic Area (EEA), which are far less economically damaging than others: but many feel that this ‘Norway option’ is ruled out because it entails retaining freedom of movement. Sovereignty also loomed large in the leave arguments. Yet most soft Brexit options involve submitting to mechanisms – such as the European Free Trade Association (EFTA) court and surveillance authority – which oversee the rules of the club. And in both the EEA and the EFTA member states are ‘rule takers’ rather than ‘rule makers’ – they have to follow EU decisions without being able to shape them. The choice seems to be all or nothing.

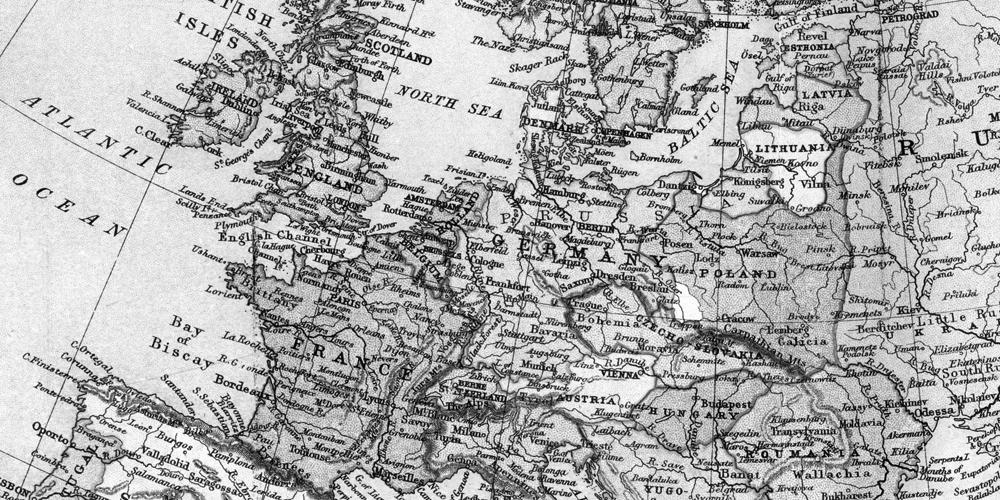

However, soon after the referendum a lamp was lit in the darkness. European policymakers proposed a ‘Continental Partnership’ – an outer ring of European states – which might provide a way forward. The idea is worthy of detailed study. This is partly because of the details of the grand bargain they propose, and partly because of the seniority of the people involved. They include the Christian Democrat (CDU) chairman of the Foreign Affairs committee of the German Bundestag, the commissioner-general of the French prime minister’s policy planning staff, and a former deputy governor of the Bank of England. However senior they are, though, they certainly are not representing official policy of the EU or individual member states.

Their Continental Partnership consists of a single market for goods, services and capital. Instead of absolute freedom of movement of people, migration quotas would be negotiated on a reciprocal basis. Members of the Continental Partnership would be more than ‘rule takers’, they would be formally consulted on issues which affected them, although the final votes on single market rules would be taken by EU states. Payments into a common budget would be the price of access to the single market. There could be close cooperation on foreign, security and possibly even defence policy. I would personally add in rules about recognition of independent trade unions and civil society organisations, employment rights, and a European-wide migrant impact fund.

The Continental Partnership has obvious attractions for British politicians searching for a way forward which encompasses an element of control over EU immigration while retaining membership of the single market. For example, it was recently endorsed by Ed Miliband.

However, when EU politicians consider Brexit and hear of the Continental Partnership their reaction changes. The reaction to Brexit has been harsh. Immigration quotas now seem like allowing British politicians a pick and mix approach to the single market. This would both reward bad behaviour and risk political contagion.

For a moment forget Brexit, and imagine yourself standing in the shoes of EU politicians contemplating what to do with non-EU members such as Switzerland, Turkey, Ukraine and even a post-Putin Russia. Or consider a thought experiment. Imagine the UK had never joined the European Economic Community in 1973, but in 2016 was eager for closer ties.

In these circumstances the Continental Partnership might now sound quite attractive. Your voters are concerned about low paid workers undercutting wages in your own countries, and therefore the immigration quotas sound reasonable. Economic ties between the EU and its periphery are deepened, but there is no requirement to join the Eurozone, which requires a degree of fiscal coordination which becomes ever more difficult with each state that joins. The governance arrangements of the Continental Partnership help give those states on Europe’s borders a voice and brings them within the European Union’s sphere of influence. Yet they do not upset the delicate balance of power which has emerged within the EU, and these new states cannot block further integration among the core EU states who wish to do so.

The end result in this scenario would be the same – the UK in a Continental Partnership. Yet it seems far more palatable. The reasons for this partly lie in the short term EU politics of the Brexit negotiations – where a hardline stance is driven by the need to maintain the unity of the EU27, and fear of copycat exits driven by populist and right wing parties.

They also partly reflect the importance of ‘anchoring’ in negotiations. The most famous example of anchoring was an experiment which asked subjects to guess the age at which Gandhi died. Half were asked, “Did he die before or after the age of 9?” The other half: “Did he die before or after the age of 140?” Those exposed to the number 9 guessed the age of death to be 50, on average. Those who heard the number 140, guessed he died at 67. This principle, in which eventual outcomes reflect the starting point, has practical implications in negotiations – guide prices in auctions and house sales are known to influence the sale price, regardless of the underlying value.

Where the baseline is Britain’s EU membership, the Continental Partnership is far less attractive to EU politicians, than where the starting point is a question of what to do with non EU members. The authors of the proposal have experienced this:

“Many also saw our proposal as useful for dealing with countries like Turkey and Ukraine, which do not belong to the EU but are seeking deeper economic ties with it. There is widespread recognition that EU enlargement has largely run its course and that another approach will be needed to deal with the EU’s neighbours. There was, however, much less consensus when it comes to the idea of applying this looser organisation of Europe to the relationship between the EU and the UK.”

This insight is useful. It helps us see that the Continental Partnership is unlikely to be achieved in the short term. It also shows the importance of the UK building alliances with countries on the European periphery: Norway, Iceland, Ukraine, Turkey and Switzerland; together with those EU member states which also might seek to leave the EU for another, looser, arrangement.

The UK would be best placed to do this as a member of the European Economic Area and the European Free Trade Association. Regular participation in these clubs would help to build up the trust and political consensus needed to argue successfully for longer term reform with the EU27. A future shift to a Continental Partnership would be easier from an ‘anchoring baseline’ which is closer to the eventual outcome. In turn, this helps us see the importance of getting the UK’s transitional arrangement right – membership of the EEA is also crucial in helping us avoid the economic cliff edge of a hard Brexit in two years’ time.

To be clear, I would prefer to remain in the EU and would be delighted if the British voters changed their minds. Yet membership of the European Economic Area in the short term, with an ambition to form something like a Continental Partnership in the longer term, seems the least harmful form of Brexit acceptable to a country which has voted to leave. More immediately, it might offer a way forward for a Labour party which faces the difficult task of appealing both to its existing voters, most of whom voted remain; and to leave voters in constituencies it must win to form the next government.

Image: Jon Ingram