Firm foundations

A Musk-style coup is hard to imagine in Britain, argues Kate Dewsnip

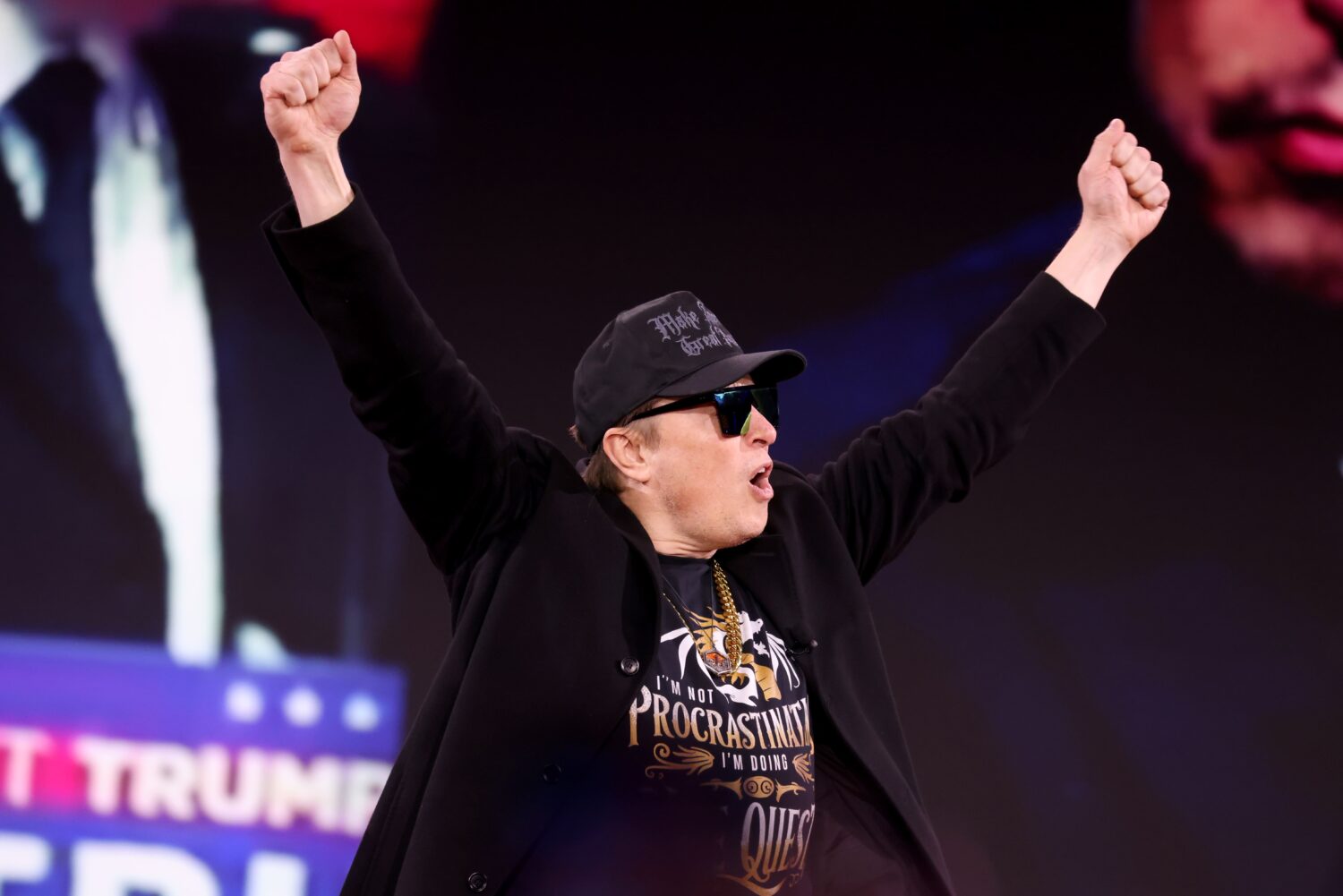

As many feared, the first few weeks of Donald Trump’s second presidential term have proven highly constitutionally controversial. From his prolific use of executive orders to dramatically expand the powers and remit of the US executive branch to his apparent contempt for the rule of law (“He who saves his Country does not violate any Law”), President Trump evidently has no issue flouting constitutional norms. Perhaps the most controversial move of all has been his appointment of a private, unelected individual to seemingly lay siege to the US’s vast federal bureaucracy. The private individual in question? Elon Musk – the world’s richest man.

Musk has been placed in this position through the creation of the Department of Government Efficiency, or ‘Doge’ for short, which he seemingly heads. Doge was established by a presidential executive order signed on Trump’s first full day in office, ostensibly to “modernize Federal technology and software to maximize governmental efficiency and productivity.” However, in recent weeks, Musk’s Doge teams have moved with unprecedented speed to infiltrate various government agencies, initiating widespread employment terminations and accessing highly sensitive government data. Unsurprisingly, such actions have triggered widespread alarm. Many have issued warnings about a lack of adequate oversight, while others have questioned Musk’s motivations, cautioning that he may use the classified information he acquires for his own personal gain. Such concerns have ultimately led to legal proceedings against Musk and his team, with a federal judge issuing a temporary injunction preventing Doge from accessing the US Treasury Department’s digital files.

In light of Musk’s rapid rise to power in the US, many in the UK are beginning to wonder: could the same thing happen here? More specifically, is the UK’s constitutional system similarly vulnerable to a ‘coup’ of the kind currently unfolding in America?

Perhaps the most logical starting point when considering these questions is to ascertain exactly what Elon Musk’s formal role is and, consequently, what the legal parameters of this role are. After a period of notable ambiguity, the White House revealed that Musk isa ‘special government employee’ (SGE), serving as a senior advisor to the president. SGEs, as defined by Title18 of the US Code, were created by Congress in 1962 to enable the federal government to benefit from the advice of experts employed in the private sector. Interestingly, the inclusion of ‘employee’ in SGE is somewhat misleading, as SGEs are only ever appointed on a temporary basis – they may only be “retained, designated, appointed, or employed” by the government for “not more than 130 days” during any consecutive 365-dayperiod. Any federal department can, and frequently does, engage experts in this manner. However, it appears that Musk is providing ‘expert’ advice directly to the president, which Trump is subsequently implementing through executive orders.

In the UK, the role most comparable to that of an SGE is a special adviser (or spad for short). Spads are appointed by individual cabinet ministers in accordance with Part1 of the Constitutional Reform and Governance Act 2010for the purposes of providing minsters with partisan advice and support. As such, they are not civil servants(although they may work closely alongside them) due to the party-political nature of their role.

The prime minister commonly appoints several special advisors, some of whom exert significant influence over government policy. Notable examples include Alastair Campbell, who served as Tony Blair’s chief adviser and press secretary; Morgan McSweeney, Keir Starmer’s current chief of staff; and, perhaps most infamously, Dominic Cummings, who was Boris Johnson’s chief adviser from 2019 to 2020. Like Musk, all of these individuals were or are unelected private figures exercising authority over their respective administration’s policy and communications.

Cummings is of particular interest here, as he consistently attacked the British civil service throughout his relatively short but impactful time in post. Just like Musk, he called for a Whitehall “revolution” and advocated for the hiring of “weirdos and misfits.” Granted, he did not go so far as to persuade the prime minister to create an entirely new government department to oversee civil servants’ performance, but the comparison still stands. It also shows that it is possible, in theory, for a Musk-style takeover to be pursued by a senior spad within the UK’s constitutional system. It is also entirely possible for a British prime minister to unilaterally create a new government department comparable to Doge, as they have almost unlimited authority to amend the structure of government.

However, in practice, the extent of what a Musk-style adviser could achieve in the UK is likely far more limited than in the US due to the role of parliament and the principle of parliamentary sovereignty. Although the British prime minister does possess powers akin to the president’s ability to issue executive orders courtesy of the royal prerogative, the scope of these powers is narrow. In response to Gina Miller’s 2016legal challenge, the supreme court determined that the prime minister must seek prior parliamentary approval to utilise their royal prerogative powers in such a manner that would affect primary legislation. Thus, the prime minister could not unilaterally enact significant constitutional change without the consent of both Houses of Parliament. Despite governments typically commanding a significant majority in the House of Commons, it is highly unlikely – at least in the current political climate – that a prime minister could persuade both MPs and peers to embrace radical constitutional changes akin to those envisioned by Trump and Musk. The House of Lords, in particular, would be highly unlikely to approve such changes.

Furthermore, the independence of the UK’s judiciary serves as a crucial safeguard against radical constitutional reforms. Unlike the US president, the prime minister has no control over the composition of the supreme court, ensuring that personal politics do not influence judicial rulings. If parliament ever attempted to limit the courts’ ability to review their actions, it is likely that judges would uphold a strict interpretation of the rule of law by interpreting ‘ouster clauses’ as ones that parliament never intended to enact. This position inconsistent with precedents like Anisminic Ltd. v. Foreign Compensation Commission (1968), where the courts maintained their jurisdiction despite legislative attempts to exclude it. Of course, it is hypothetically possible that a tyrannical government, emboldened by a rebellious parliament, could ignore such a judgment; however, no British prime minister has ever refused to abide by a supreme court ruling (even Boris Johnson promptly reconvened parliament in the wake of the second Miller judgment). If that were to happen, the British constitution would be left in tatters.

Ultimately, although a hostile takeover of the Executive by a private individual is theoretically possible, it is highly improbable in practice. Although uncodified, the UK’s constitution incorporates robust checks and balances that have historically functioned effectively. As discussed above, for an individual similar to Musk, even with the backing of a complicit prime minister, to impose tyrannical rule and undermine the current constitutional system, they would need to persuade the Cabinet, both Houses of Parliament (Commons and Lords), and the supreme court of their cause, or somehow bypass these institutions entirely – rendering the success of such an endeavour extremely unlikely.

Image credit: Gage Skidmore via Creative Commons