Hearing their voices

How do Scottish voters see their future – and how might Labour win them back? Martin McCluskey and Katherine Sangster report on new Fabian research.

Next year, the people of Scotland will vote in the sixth Holyrood elections against the backdrop of a pandemic, an economic crisis and renewed calls for a second independence referendum. The clamour for another referendum has been buoyed by polls showing a majority for the pro-independence side.

But what does Scotland want its future to look like? Over the past year, the Scottish Fabians – in partnership with the Foundation for European Progressive Studies – have been researching the views of the Scottish public on the past 20 years of devolution and their expectations for the future. In the New Year, we will publish our findings in full.

Our interim results have revealed a Scotland that is full of contradictions. People are satisfied with the current devolution settlement and have a desire for more to be decided in Scotland. But many still do not understand where power lies and who has control over their public services. There is often dissatisfaction with the delivery of these services, but a reluctance to hold the politicians who are in charge to account. And many people are sceptical about independence but enthusiastically support the Scottish National Party either as an expression of their identity or because they see no viable alternative.

Donald Dewar, Scotland’s first First Minister, envisaged a parliament that would be the focal point of Scottish political life and would finally put to bed the constitutional wrangling that had been a key feature of Scottish politics since the 1960s. With 20 years of legislating behind it, Donald Dewar’s wish has in part come true and our devolved institutions are now firmly fixed in the Scottish political landscape. The vast majority of Scots support the Scottish Parliament and only one in 10 would prefer all power to be returned to Westminster. It is easy to forget that in the early years of the parliament, it was ridiculed by the media and treated with suspicion by the public.

The Scottish government has never been more powerful, yet the devolution settlement has never been more fragile. It risks being pulled apart by the SNP, whose objective has always been independence, and a Conservative party which is still deeply sceptical of devolution.

Power and the parliament

From the very early days of devolution, the Scottish parliament held wide-ranging powers with full control over education, health and justice – powers which have been expanded in recent years. Despite this, our research has shown a gap in understanding about who has power over what in Scotland.

Polling we commissioned from YouGov found 27 per cent of people wrongly believe that the Scottish NHS is controlled by the UK government and 21 per cent similarly believe that control of police and criminal law is in Westminster’s hands. Nearly a third of people believe that the Scottish government is responsible for social security, even though the most significant social security spending (such as universal credit) is determined by the UK government. Thirty one per cent of people believe employment law – a policy area that is frequently discussed as a candidate for devolution – is already devolved. And only 55 per cent of people know that income tax rates – devolved with significant fanfare in 2016 – are now under the control of the Scottish government.

Despite this lack of clarity about who does what, the Scottish government and members of the Scottish parliament command far higher levels of trust than their UK counterparts. While 31 per cent of people would not trust MPs ‘at all’, only 18 per cent of people feel the same about MSPs.

Our findings present significant challenges for Labour and all opposition parties. First, when a significant proportion of the population is unable to identify the responsibilities of the Scottish and UK governments, it does not bode well for accountability and scrutiny.

Second, it calls into question the approach taken over the past decade of devolving more powers in an attempt to find a stable settlement to answer demands from people across Scotland for more control. Whilst these moves may have been necessary, the fact that they were clearly insufficient suggests there are deeper emotions and beliefs driving support for further devolution. Understanding and responding to these will be key to successfully making the case for continuing with a strong Scottish parliament inside the United Kingdom.

Identity

The theme of Scottish identity ran through our research. There has always been a strong sense of national identity in Scotland and this has often been used in political debate. Labour successfully made the argument that Scotland was at the mercy of a government it did not vote for in the 1980s and 1990s. Today, the SNP uses the same argument.

The legacy of both the 2014 and 2016 referendums still looms large in Scottish politics and the result of the former has come to define how many people in the population vote. Whilst the ‘no’ vote won in 2014, the independence vote coalesced around the SNP. And the fallout from the Brexit vote in 2016 has resulted in a slow drift of some ‘no’ to independence voters to ‘yes’, causing independence to nudge ahead in the polls.

The effect of the independence referendum in particular, and the lack of any alternative unifying political force, has pushed many voters to the extremes. Our research shows that nearly six in 10 Scottish voters now consider themselves ‘unlikely’ to vote for a party that does not share their position on the Scottish constitutional question – such is the extent that this choice has come to define Scottish politics.

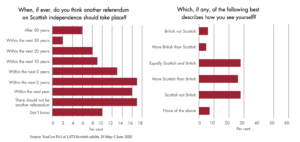

Scottish identity is strong among the population in Scotland, with a majority of people considering themselves Scottish ahead of British (if they have a British identity at all).

These sentiments are unsurprising. Scotland had its own legal and educational system long before devolution but this strong Scottish identity has not always been linked with a belief in political nationalism.

Devolution has not succeeded in encompassing Scottish identity within the broader framework of the United Kingdom. The dual referendums of 2014 and 2016 created a Scottish identity which opposed a British nationalism represented by successive Tory governments and ultimately the Leave vote. Findings from focus groups conducted as part of our project show that there is now a far stronger link between reported identity and political preference. In the current political climate, that has benefited the SNP and the Conservatives which both have clear distinguishable positions on these constitutional questions.

How should Labour respond? The party’s natural inclination is to reach for an economic response instead of addressing the issue of identity head on. This failure has left Labour in recent years with little to say to the majority of Scots who are fiercely patriotic and who want to see their Scottish identity reflected in their politics. Our research suggests that Labour needs to be able to speak to the patriotic majority of Scots if it is to ever succeed in the future.

Breaking the link between cultural and political nationalism is crucial both to winning another independence referendum and revitalising the Scottish Labour party. The Scottish Labour party has to learn from its own history and from that of European regional parties. Any solution has to be grounded in a well-developed view of Scottish identity that differentiates Labour from the SNP and does not resort to tactical devices (such as an ‘independent’ Scottish Labour party) which will only further alienate voters.

Finally, Scottish Labour should not put itself on the wrong side of the debate around a second independence referendum. Our research found no enthusiasm for another referendum in the next year or two. However, 46 per cent of voters support another referendum in the next five years and only 17 per cent would never support one.

The next 20 years: a constitutional settlement for the majority

The lack of a strong party defending and arguing for devolution has put the settlement at risk from both the SNP and the Tories. While, in some polls, independence now has the support of a majority, this is not the case when presented against a range of other constitutional options.

There is a clear space opening up in Scottish politics for a party that is capable of making the argument for a progressive devolution that works within the UK as the debate is now polarised between independence and the increasingly defensive unionism of the Conservatives. We must ask ourselves how can we articulate Scottishness and how does it relate to Britishness? So far we have engaged in an auction of powers but after Brexit we must make any further devolution part of a wider debate over where powers sit in the UK.

Image credit: Sinitta Leunen on Unsplash