Losing faith

Low turnout in 2024 reflects widespread dissatisfaction with our democracy, argues James Prentice

A much remarked-upon yet largely unexplored theme of the last general election was voter apathy. Across all constituencies, turnout declined by 7.6 percentage points, bringing it to a historic low of less than 65 per cent. This was supposed to be a ‘change’ election, so why did more than a third of voters stay at home? It is worth looking at constituency results and British Election Study (BES) data to identify reasons for the low turnout.

![]() Voters in Conservative party heartlands staying at home.

Voters in Conservative party heartlands staying at home.

One common assumption is that the low turnout resulted from voters in Conservative party heartlands staying home because they had become disillusioned with the government’s incompetence and lack of ethics. However, this assumption might be wrong. For one thing, turnout decreased most in seats that voted Labour. This was especially true in seats that Labour won in both 2019 and 2024; on average, these seats displayed 2 per cent greater decreases in turnout than other seats. In comparison, seats the Conservatives held experienced lower-than-average declines (less than 6 per cent), with more than 75 per cent of these seats experiencing smaller declines than the seats Labour held. Therefore, this year’s turnout decrease was primarily caused by apathy in relatively Labour-leaning constituencies. Because the Conservatives performed so well in Labour heartlands in 2019, many of these lost voters were likely recent Tory voters.

A belief that no party could deliver economically, or on their core concerns.

Interestingly, those who decided not to vote did not have significantly different concerns from those who participated. Roughly 35 per cent of both voters and non-voters stated that they felt the biggest issue facing the country was the state of the economy. Immigration was the second most cited issue, with health being the third. Essentially those who decided to stop participating were thinking about the same issues as those who voted.

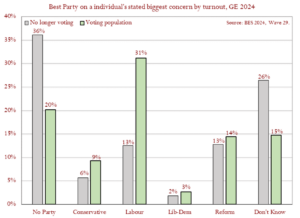

Figure 1: Best party on an individual’s number 1 concern, new non-voters compared to the electorate. Source: BES 2024.

However, those who stopped voting tended to be much more sceptical of any party’s ability to deliver, with 36 per cent stating no party could deliver on their biggest concern (compared to 20 per cent of voters) and 26 per cent not knowing which party could deliver (compared to 15 per cent). Only 13 per cent believed that Labour was the party best-placed to deliver on their highest-priority issue, compared to 31 per cent of the voting population, as figure 1 shows. This group was also likely to state they did not think that either the Conservatives or the Labour party were competent. As people who stopped voting were disproportionately on lower incomes, they may have been hit harder by the inflationary spike experienced after lockdowns were lifted. Consequently, the economic hardship experienced by this group may have made them feel it was not worth their time voting.

A belief that no party provided the effective leadership and vision needed to fix the country’s many problems.

Another noticeable trait amongst those who decided to stop voting was that they were much more likely to dislike both main party leaders. A majority of these non-voters disapproved of the leadership Sunak offered, and a greater proportion didn’t approve of Starmer (19 percentage points more than the voting population).

These new non-voters felt the main parties did not have the ideas needed to improve the country: 60 per cent of those who did not vote stated they felt the Tories had run out of ideas, and 30 per cent said the same about Labour – 12 percentage points more than the general population.

A general dissatisfaction with the political system and a feeling that no party could be trusted to hold office due to previous scandals.

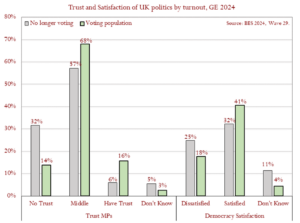

The root cause of declining turnout may be more deep-rooted dissatisfaction about the state of British democracy and its representatives. Individuals who chose to disengage more often stated that they had no trust in any MP, with roughly a third saying they did not trust their representatives, 18 points more than the general population. Figure 2 also demonstrates they were more likely to say they were dissatisfied with the overall state of UK democracy. This is a worrying picture: people may not be voting not only because they think parties cannot deliver on their core concerns, but also because they do not trust the system as a whole to have their interests at heart.

Figure 2: Trust and satisfaction with UK democracy, non-voters compared to voters. Source BES 2024.

Recent controversies over politicians’ behaviour may have been particularly corrosive. We know, in particular, that many people who had made sacrifices during the Covid-19 pandemic were upset over Boris Johnson’s lockdown rule-breaching parties. The fiasco of Liz Truss’s short-lived government is also likely to have undermined faith in politicians. Then there were the stories which broke during the election campaign of senior Conservative MPs using their prior knowledge of the election date to place profitable bets with several bookmakers. All of these issues will have added to people’s distrust, potentially convincing some individuals to not bother voting.

Voters believing Labour would win, or just not caring?

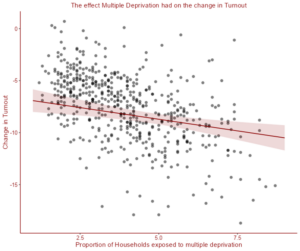

This theory is the hardest to test due to the limited data available. However, there are some clues at an aggregate level. Figure 3 shows that the areas that tended to see bigger decreases in turnout were areas higher in deprivation. Overall, turnout was suppressed the most in areas where Labour won, multiple deprivation was high and the population was more likely to rent. Figure 3 shows that turnout declined by half a point when the level of multiple deprivation increased. This means that in areas with the highest deprivation turnout decreased by as much as 4 points more than the national average, making it the most influential factor in decreasing turnout. The next most significant factor was the proportion of people who lived in rental accommodation, with areas with high levels of renting seeing a 2.5 point decrease in turnout. When Labour retained a constituency this decreased turnout by 1.3 points and the seats they gained saw a 0.8 point decrease in turnout.

Figure 3: The proportion of households exposed to multiple deprivation and the change in turnout for each constituency in England, Wales and Scotland.

This suggests that Labour could have a problem with engaging their voting base in these traditional Labour areas. Individuals from deprived communities in Labour strongholds may have felt the party did not have the vision needed to tackle the many challenges their communities face. For example, the lack of a focus on the growing issues of poverty and investment in declining public services may have caused some to think a Labour government would not bring the change many were looking for, thus making voting not worth the effort.

Conclusions:

Overall, the decline in turnout was particularly significant among individuals living in deprived communities dependent on rented forms of accommodation who seem not to have believed the political system would cater to their interests or needs. Rather than this being about a specific leader, it instead represents a wider disapproval of the democratic system. The decline in turnout can’t be fully explained as voters in Tory heartlands staying at home or Labour voters being complacent and thinking their party would easily win. Rather there seems to have been a more deep-rooted negative feeling that the political system simply could not be trusted.

Yet, if Labour can win the trust of these new non-voters, it could produce important returns. Labour lost 504,500 voters simply from people disengaging: if it could re-engage these apathetic voters it could gain a significant boost in support. With many key marginal constituencies seeing heavily split votes and some Labour MPs having majorities of just a few hundred, this could help Labour win again next time around.