Repair and reconciliation

With Barbados having now removed its final tie to the British Empire, it is time for the Labour party to listen up: the Caribbean is demanding reparations and expects your support. Verene Shepherd explains

This november, on the 55th anniversary of independence, Barbados formally became a republic – renouncing the final vestiges of control held by the British monarchy. This feat by Barbados (the fourth Caribbean nation to remove the Queen as head of state) secured another cog in the revolving wheel towards sovereignty and reconciliation taking over the Caribbean.

Across the Caribbean people are taking demands for justice, dignity and respect further, adding their voices to the worldwide call for reparations from former colonial countries in Europe like Britain.

The reparations movement is a global one that has been described as the greatest political movement of the 21st century. Its demands should be essential to Labour’s vision, with the party’s renewed commitment to racial justice following last summer’s Black Lives Matter protests: Reparations are vital to eliminating racial inequality.

The reparation movement has a long history: It was started by the Indigenous Peoples and enslaved Africans, including Maroons, who understood the evils of capture, land conquest, trafficking and chattel enslavement.

Today, reparation commissions have been launched, or are in development, in the United States, Canada, Brazil, Venezuela and in Europe – namely Sweden, Switzerland, Germany, and the Netherlands. In South Asia, Narendra Modi, the prime minister of India, and Shashi Tharoor, a member of parliament, have also called on Britain to pay reparations to India for the damage done during 200 years of colonial rule

And in the Caribbean, the movement for reparations turned a corner in 2013 with the formation of the CARICOM Reparations Commission, of which I am vice chair.

The Commission has been establishing the moral, ethical and legal case for reparation to the Caribbean community for transatlantic trafficking in Africans, genocide, a racialised system of chattel enslavement, deceptive Indian indentureship, and the continued harm from these legacies.

Since its formation, the CARICOM Reparations Commission has received support from the Pan-African Congress, human rights organisations, and the international media – solidifying its prominence in modern discourse on human rights abuse, reparatory justice, and reconciliation. It is imperative for Labour to recognise the magnitude of this movement and engage in the conversation on a wider scale.

With so many countries supporting reparations, the movement has finally achieved greater global visibility. Reparations can no longer be viewed by British political parties as a quiet plea, but one which has momentous support amongst nations with key diplomatic ties to Britain. Moreover, it must be recognised as a plea shared, to varying degrees, by the entire African diaspora – a community that is often marginalised in political and social discourse. Labour must recognise this and begin to provide a platform for its underrepresented voters.

Why do former colonies need reparations?

At the core of the transatlantic trade in Africans and the system of chattel slavery was the dehumanisation of people on the basis of ‘race’; a social construct that, to this day, shapes access to fundamental human rights.

At present, former colonies are underdeveloped and experiencing state failure. This is intrinsically linked to the ravages of slavery on their indigenous lands, economies, people, and societies which must be rectified. Though Haiti is one of the more concerning examples of state failure resulting from slavery, former British colonies like Sierra Leone have endured decades of underdevelopment and failure due to the poor governance from social and economic systems emerging out of British colonisation.

International law helps us establish precedent within our claims. Famous cases such as the reparation extracted from Ayiti by France; reparation paid to the Jews; and reparation paid to the British planters at emancipation all support the call that reparation can and should be provided for past wrongs.

What do our demands for reparation look like?

Reparation comes from the Latin word for ‘repair’. Broadly, reparations can come in the form of a payment; an apology and acknowledgement of past wrongs; or by enacting practices, policies and systems to ensure that victims are given the right tools to move forward.

The Caribbean reparation movement asserts that we must collectively “remember, reclaim, restore and repair to secure rights and achieve reconciliation” (the six Rs), on behalf of the five million Africans forcefully relocated to the Caribbean and their descendants who continue to live with colonialism’s legacies.

The CARICOM Reparations Commission has created a 10-point plan to negotiate with former colonisers. Amongst our demands include a full formal apology; development programmes for Indigenous communities; the return of cultural heritage; psychological rehabilitation; education programmes; debt cancellation; and monetary compensation.

For the Caribbean reparations community, receiving a formal apology for historical abuses is an important first step. An apology recognises the pain and the human rights abuses that were perpetrated by these systems. Repair and reconciliation cannot be truly achieved without the acknowledgement of past wrongdoings.

Support for developmental programmes, debt cancellation and monetary compensation will further aid former colonies to fill the development gap that was caused by colonisation. With European states leaving their colonies without functioning economies and social and political systems, these nations have endured a tedious journey towards development and growth. By injecting financial assistance and infrastructure into former colonies, a more equal global system will be created.

To this end, the United States Virgin Islands, inspired by the Caribbean reparation movement, has made significant progress in advancing reparation claims from the government of Denmark. In addition to formal apologies being made by the Danish royal family and government, Denmark agreed to provide financial support for cultural and educational development programmes.

The movement is also pushing for change across several elite universities. And in Glasgow, Cambridge, Bristol, Liverpool and Edinburgh, universities have started investigating the extent to which their institutions benefited from slavery. The historic Memorandum of Understanding which was signed between the University of the West Indies and the University of Glasgow, signalled their intention to partner in a reparation strategy and is yet more proof of this movement’s global identity.

Where does Labour fit in to the global reparations movement?

Reparation must be seen by Labour as an all-encompassing process that directly addresses the racial injustice and inequality that emerged because of slavery. To support reparation, then, is to acknowledge the legacy of pain many citizens have endured because of their racial ancestry.

Racial inequality in the UK today is directly linked to historical structures of inequality and abuse. Labour should support the reparations movement, then, because it speaks on behalf of the marginalised voting population in Britain who are impacted by racial inequality.

The way forward is for Labour to engage with and promote the ‘six R’s’ both at home and internationally. Ideally, to accomplish this Labour must be willing to approach the reparations dialogue with an open and proactive mind. An annual Remembrance Day to commemorate the abolition of slavery may act as a significant way forward.

Yet the party has previously fallen short in its support of reparations.

In 2007 Tony Blair, then Labour leader and prime minister of the UK, disappointed the Caribbean amidst expectations that he would use the bicentenary of the passing of the Slave Trade Act to apologise for Britain’s role in the maangamizi – a Swahili term which refers to the African holocaust of chattel and colonial enslavement.

While Blair expressed ‘deep sorrow’ that the transatlantic trade in enslaved Africans ever happened, he stopped short of offering an apology. Keir Starmer can correct this.

Unfortunately, Britain feared that a full, formal apology would open the country to claims for reparation. This line has been taken by subsequent UK prime ministers including David Cameron. The response to a 2016 letter setting out the reasons the UK should meet and talk reparation with representatives from the Caribbean was not met with a positive response.

There are, however, Labour MPs like Diane Abbott and David Lammy who think the Caribbean’s claim is just.

Now, for Labour to assume a leadership role in addressing reparations, the entire party must support this movement and recognise its moral and ethical obligation to critically examine Britain’s role in the global system.

As we celebrate Barbados removing its final colonial ties, the time is ripe for the party to take leadership on this issue. The world is looking to Britain’s role in the Caribbean and Labour must step up: it is time to throw its support behind the CARICOM Reparation Commission in its struggle for justice.

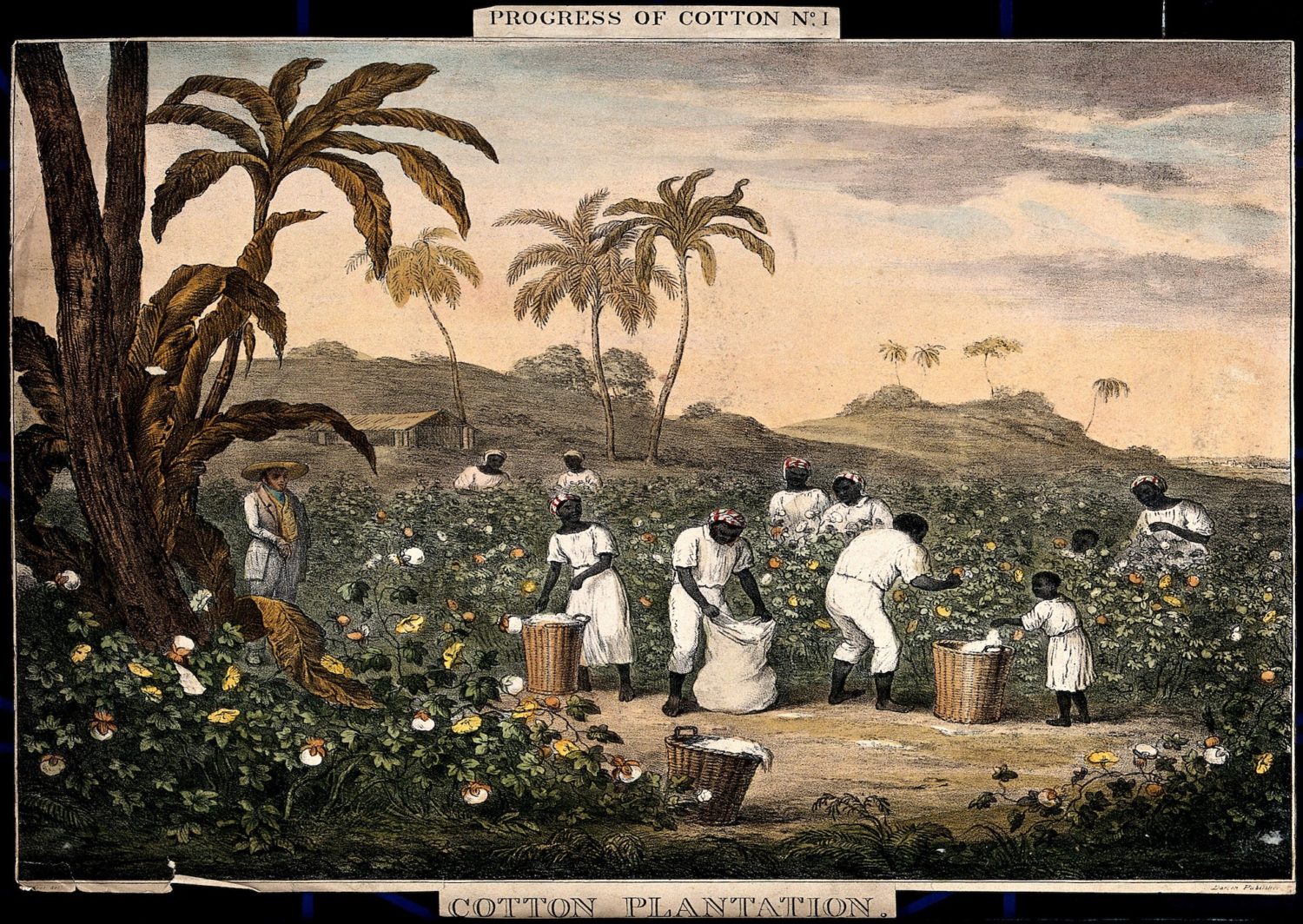

Image credit: James Richard Barfoot/Wikimedia Commons