Repairing care

We are in urgent need of a politics that puts care at its heart, write Lynne Segal and Jo Littler.

The coronavirus crisis has simultaneously shown just how crucial care is for our lives and just how uncaring our society has become. Turning Beveridge’s post-war welfare promises on their head, we now have a lack of care operating at every level – from cradle to grave. The majority of parents have less time to care for children, often battling exorbitant childcare costs and working ever longer hours, the load disproportionately falling on mothers. Youth services have been all but eradicated, when they are most needed, with rising stress at all ages. The calamity of social care, especially for disabled and older people, has been mounting for years in these cruel times of ‘peak inequality’, as Danny Dorling terms it. Those caring for older relatives or spouses have found it increasingly difficult to access resources or respite, leading to frequent depression, especially for home carers already struggling with poverty. Public care provision has become increasingly inaccessible, with services largely dismantled and outsourced to corporate commodity chains. These corporations so often create intolerable conditions for their workers – who are insecure, underpaid, on zero-hours contracts – whilst viciously curtailing the continuity of social and nursing care, as captured so movingly in Ken Loach’s latest film, Sorry We Missed You. Thus, while massive profits have been made from outsourced ‘care’, its provision largely mocks its very name, creating little security for either the cared-for or the carers.

All of these examples of structural carelessness are the direct result of privatisation and outsourcing of the welfare state over the past four decades, in tandem with the savage austerity cuts we have faced since 2010. Their consequences are everywhere: in the rapid emergence of 2,000 food banks; in another child becoming homeless every eight minutes; in heightened stress in the workplace and the home; in increasing rates of loneliness and mental illness (one in four now suffer from depression). Meanwhile, the cuts to the NHS, its partial privatisation, the removal of nursing bursaries and deteriorating conditions across the care sector have seriously undermined our health system. Seventeen thousand hospital beds have been lost in the past decade alone, with a reduction of 100,000 NHS staff, including a shortfall of 35,000 nurses and 10,000 doctors. This is the background to our current intensified crisis. It parallels a callous lack of concern for the plight of refugees and rising xenophobia, as well as continuing refusal to deal adequately with climate change or shrinking biodiversity. This is why we say, in the footsteps of others, that the crisis of capitalism today is above all a crisis of care. Care was already the issue of the moment, long before Covid-19 hit us.

How is this crisis of care affecting us during the pandemic? The UK currently has the worst death rate in Europe due to our government’s multiple forms of carelessness. It refused to take heed of warnings of future pandemics following SARS and MERS, unlike South Korea. It responded far too late, with the prime minister flamboyantly refusing to take social distancing seriously at the critical early stage, unlike other countries, most prominently New Zealand. It had over the last few years already curtailed and abandoned structural pandemic preparation. It had slashed hospital resources, including the number of nurses and hospital beds, providing less than half the number of ventilators of German hospitals. It did not respond to co-ordinated EU strategies to provide personal protective equipment, unlike much of the rest of Europe. Its inadequate, part-privatised and continuously reordered infrastructure proved inept at establishing a system to test frontline workers in any health emergency. Meanwhile, care homes were to a large extent abandoned; whilst untested occupants and workers were left exposed to the virus and treated with utter negligence – the deaths of their older inmates not even recorded in the announcement of Covid-19 mortality rates over the first five weeks. The disastrous results are the record spreading of the virus in Britain, surpassed only by the USA, including the deaths of at least 164 health workers, disproportionately BAME.

Yet this global calamity is also a moment of profound rupture, where many of the old rules no longer apply – and where governments appear to have changed those that remain overnight. How might this moment help us initiate more lasting changes? If the pandemic has taught us anything it is that we are in urgent need of a politics that puts care at its heart. It is a stark reminder of the importance of creating robust care services. We must reinstate bursaries and scrap fees for trainee nurses, raise their poverty pay and protect and take heed of whistleblowers (who are, even now, being sacked for revealing dangerous practices). We have to bring an end to the waste of privatisation and contracting out by demanding the insourcing of services. We need adequately-funded public hospitals and care homes that are within the public sector and accountable to those who use and service them, rather than frittering away our money on private corporations. The time for universal basic services is now.

But it is also important to emphasise that care is not only the ‘hands-on’ care of directly looking after the physical and emotional needs of others. It is also about recognising our interdependence, throughout life; and our ever greater global interdependence, as well as our shared vulnerability. Therefore, caring is about rebuilding our welfare and community resources from the bottom up, as well as the top down, to enable us all to develop and use our capabilities to flourish and lead engaged and meaningful lives: for we can only really flourish in a flourishing world.

What would a world organised around care look like?

Beginning with kinship, in recent times our circles of care have shrunk to the ever-narrower level of the individual or the nuclear family. Instead, we need to broaden this out again, learning lessons from current and earlier mutual aid and alternative kinship practices. Today it is clearer that people can actually enjoy caring, whatever its challenges, when they have the time and space, despite the ambivalence that easily accompanies caring responsibilities. Caring for and about others helps us to appreciate our shared and fragile humanity, helping us to acknowledge rather than disavow our own fears and dependencies. That is what makes for a good life; we might even say, after John Berger, a fortunate life.

As feminists have long fought for, centring care also means further degendering it, since care has overwhelmingly fallen on women’s shoulders. But the government’s response to the pandemic has only entrenched sexism. For instance, it did not allow furloughing to be taken part-time, which would have made it easier for men and women within dual-income households to share equally both childcare and paid work.

Beyond the pandemic, we must level up on equality, shortening the working week and teaching boys as well as girls emotional literacy and the diversity of caring skills, beginning with the domestic. We need to ‘de-race’ caring, given that historically and increasingly today, hyper-exploited caring jobs are predominantly undertaken by BAME and migrant women. In today’s global care chains, women often leave behind their own children and dependents in poorer countries, in order to make up the care deficit in richer countries. This is the moment that we must demand an end to the economic exploitation of care workers, and not just clap for them.

Reimagining care also means rethinking our communities. Adequate care cannot be separated from enriching the neighbourhoods we inhabit. Above all, this means shared public resources for all: reinstating the importance of public libraries, schools and parks, and extending our capacities to share in new ways: from tool libraries to public broadband. The new municipalism – like Preston’s reinvigoration of local organisations and facilitation of co-operatives – is exemplary here, as are the successful campaigns for ‘insourcing’ in universities and local councils. A ‘caring commons’ enables us to connect and support each other in our complex needs and mutual dependency. Building people’s ability to participate in the world, giving them a significant stake in the care they give and receive, and extending local democracy is how we really take back control in a sustainable and pleasurable rather than destructive and proto-fascistic form.

Finally, the only way out of our current ecological mess is by taking these forms of care further, ensuring caring states with sustainable economies. As Ann Pettifor and others have demonstrated so persuasively, this involves implementing a Green New Deal on a transnational level, whose goals are sustainable futures, ensuring that the world’s population and the world itself is cared for.

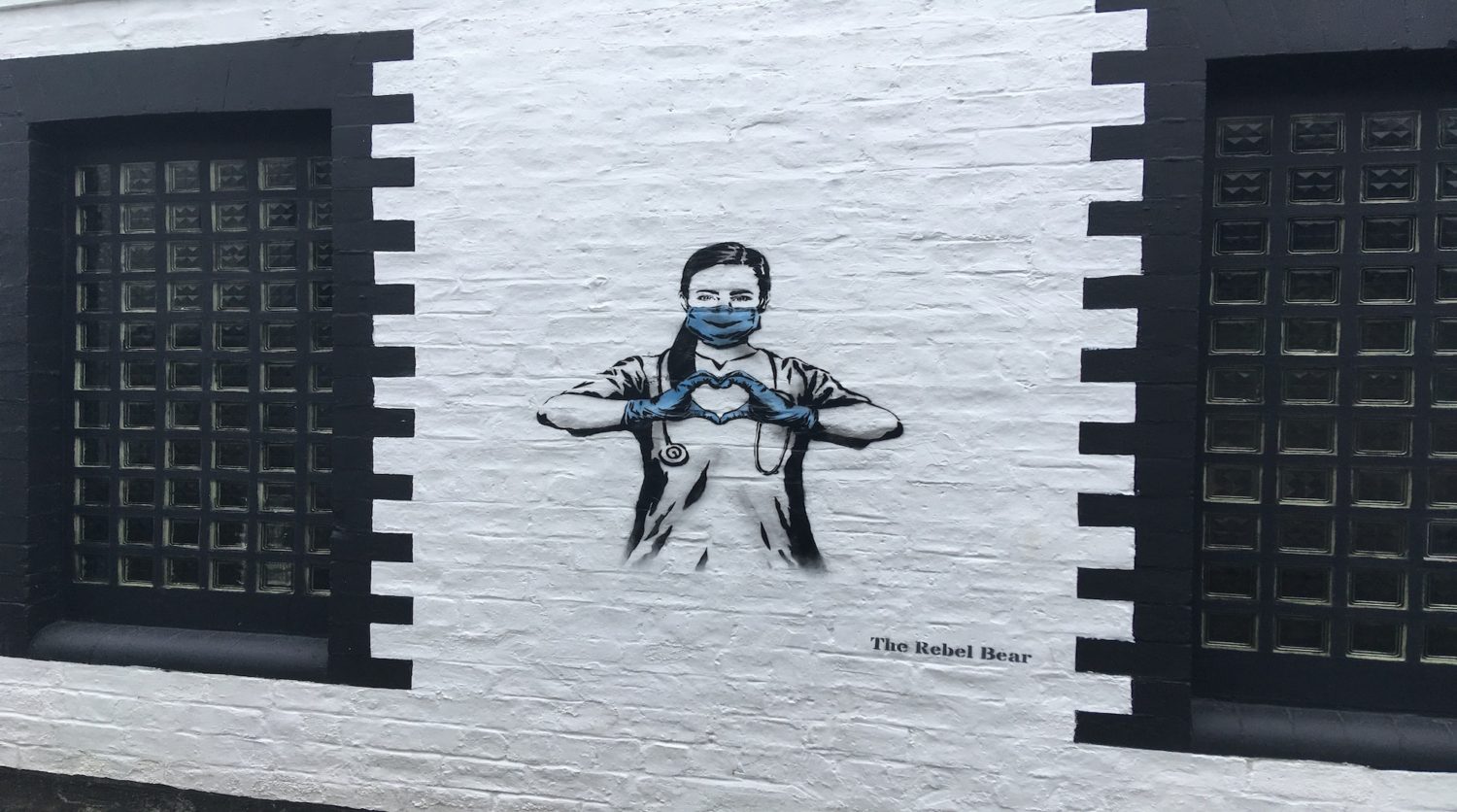

Care might be in the air: we had the Thursday night clap for carers; the word is emblazoned on lapel pins and in all kinds of corporate ‘carewashing’ advertisements; ‘care’ is even a new Facebook emoji. But to bring it down to earth – to be able to care more – we must both fully recognise our interdependence and repair our broken and neglected model of care at every level.