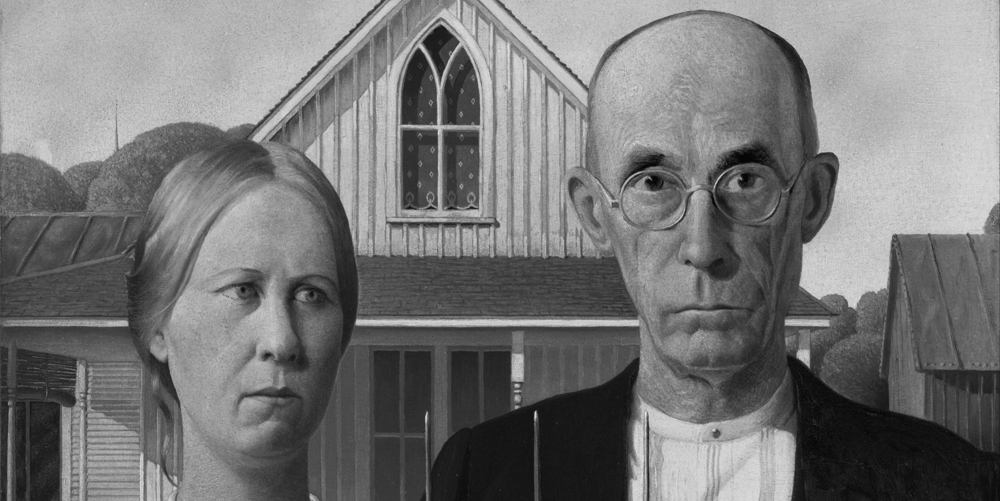

Rural America: ‘A silent majority’

For the British viewer, Tuesday’s US presidential election night coverage unfolded in eerily familiar fashion to the Brexit referendum night. Premised on early voting that suggested huge Hispanic turnout in urban Florida and Trump’s weak showing in typically Republican cities,...

For the British viewer, Tuesday’s US presidential election night coverage unfolded in eerily familiar fashion to the Brexit referendum night. Premised on early voting that suggested huge Hispanic turnout in urban Florida and Trump’s weak showing in typically Republican cities, such as Jacksonville, pundits were predicting easy victory for Hillary Clinton and an early night for their audience. Even Trump’s campaign manager appeared on television deflated and in the mood to start the blame game for his presumed defeat. As in June, however, the conventional wisdom was quickly upended by the emergence of startling results. In the case of Brexit, it was Sunderland; on Tuesday, it was the rural white vote in Florida. Indeed, as soon as the results from rural counties in the Sunshine State started to flood in, it quickly became clear that Clinton was in trouble and that the night would be long.

In attempting to explain Trump’s shock victory over Clinton, much analysis has focused on the white working-class in Rust Belt states, such as Michigan and Ohio, who, having voted for Barack Obama in 2012, cast their ballots for the New York billionaire in 2016. Others meanwhile have pointed to the lack of enthusiasm for Clinton from parts of Obama’s ‘Coalition of the Ascendant’ – namely younger and African-American voters. Another key feature of Trump’s perfect political storm, was undoubtedly his ability to win the votes of rural white America to an extent that far surpassed previous Republican levels. Certainly, exit polls suggest that voters who reside in either rural or small town America supported Trump by a margin of 28 per cent – eight points more than the plurality enjoyed by Mitt Romney in 2012 – thus providing the decisive margins to outweigh the Clinton vote coming from the cities in a host of battleground states.

The urban-rural divide in the United States is not a new phenomenon, culturally it goes back as far as the industrial revolution itself, but it was the 1920s that witnessed the divide become increasingly political. In 1920, the American census recorded that the number of Americans living in urban areas had surpassed those living in rural America for the first time in the young nation’s history. It was perhaps no coincidence, therefore, that the ensuing decade witnessed the resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan and the passage of strict immigration laws, as rural America exerted its political power over immigrant-heavy cities that were often internally divided between Germans and Italians, Swedes and Poles. In 1928, when the Democratic Party nominated Al Smith, a candidate described by one historian as being “as urban as the Brooklyn Bridge,” larger cities became more united than ever before at the presidential level. Nevertheless, suspicious of his Irish-Catholic background and urban ways, Al Smith was repudiated by rural America and, with the help of smaller cities, emphatically defeated.

The Great Depression and the presidency of Franklin Roosevelt stirred some unity between farmer and factory worker during the 1930s and 1940s, as voters from both the city and the country bought into the New Deal. Roosevelt himself viewed American farmers as the backbone of the United States, and the New Dealers spent equal time trying to help the rural American, as they did the struggling urbanite. Following Roosevelt’s death in 1945, however, rural voters – except for loyal Democrats in the South – began drifting back to the Grand Old Party (GOP) over the next twenty years.

In the 1960s, the combination of African-American civil rights success and race riots in American cities served to push rural America firmly into the GOP column. Southern rural areas were the first to go, as large swathes of the white South voted for Republican Barry Goldwater – largely as a reward for Goldwater’s vote against the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and also his nostalgic vision of a bygone America. Northern rural and small-town areas followed not long after, as polls revealed that, despite not being directly affected, it was these voters who were most alarmed at the race riots that became a frequent occurrence in American cities during the 1960s. Drawn to Richard Nixon’s promise of ‘law and order’, these voters made up a significant portion of Nixon’s ‘silent majority’. With the odd exception, rural America has remained firmly in the Republican column in presidential elections ever since.

Fast forward to this year’s election, and the question is why did such a large percentage of rural America plump for the most urban of candidates? Raised in the Bronx, and as out-of-step with evangelical Christianity as a Republican candidate has arguably ever been, Trump seems a strange choice for rural America to make.

Arguably, there’s a few things at work here. Firstly, the issues; rural conservative voters prefer a more racially homogenous society and Trump’s nativist views on immigration, which formed the core of his campaign, clearly struck a chord. Secondly, partisanship; rural America is a Republican heartland in an era of stark political polarisation. Even if many rural Americans were put off by Trump’s character, few could stomach the thought of putting Hillary Clinton – a Republican bête noire – in the White House. Finally, Trump; even if his status as a brash urban tycoon appears antithetical to rural voters on paper, Trump’s shtick had an everyman machismo to it that appealed in an area of the country that feels looked down upon by the coastal elites. A mixture of these factors then, likely led rural America to play a key role in President-Elect Trump

Ultimately, for all that this election has the potential to trigger a realignment in American politics, it is unlikely that any substantial shift will happen in rural America – just as it is similarly unlikely that New York or San Francisco will suddenly start voting Republican. Both parties will likely focus much of their strategy on the white-working classes in smaller cities and the suburban middle-class. As such, America’s rural-urban political divide appears poised to continue for generations to come.