Socialism in the sixties

The work of Richard Titmuss can tell us a great deal about the left's view of social welfare in the 1960s - and beyond, writes John Stewart.

In early 1959 Peter Townsend wrote to Richard Titmuss on behalf of the Fabian Society. The society was, he told him, drawing up its autumn lecture programme and his colleague ‘Tony Wedgwood Benn has been very anxious to see if we could ask you to give one lecture’. Townsend and Benn had been trying to make the programme ‘as impressive and forward looking as possible’, and to that end had managed to ‘reduce the hack politician representation’. Titmuss eventually agreed to contribute to the series, whose overall theme was ‘Socialism in the Sixties’.

In early 1959 Peter Townsend wrote to Richard Titmuss on behalf of the Fabian Society. The society was, he told him, drawing up its autumn lecture programme and his colleague ‘Tony Wedgwood Benn has been very anxious to see if we could ask you to give one lecture’. Townsend and Benn had been trying to make the programme ‘as impressive and forward looking as possible’, and to that end had managed to ‘reduce the hack politician representation’. Titmuss eventually agreed to contribute to the series, whose overall theme was ‘Socialism in the Sixties’.

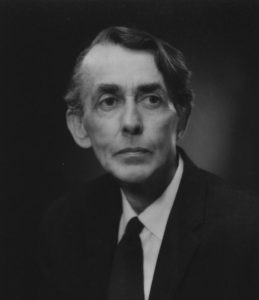

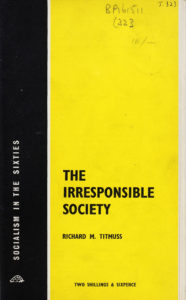

So who were these three? Who, in particular, was Richard Titmuss, and what came of his Fabian Society speech? Townsend was a sociologist, at this point based at the London School of Economics, working on poverty and what was shortly to be called ‘relative deprivation’. Wedgwood Benn was a rising star of the Labour party, soon to be a government minister, and later darling of the Labour left. Titmuss was professor of social administration (what we would now call social policy) at LSE who had, since his appointment in 1950, at first almost single-handedly created the academic field of social policy. He did this both through his own research and by way of the new members of staff he progressively appointed, many of whom went on to become prominent social policy experts in their own right – Townsend being a case in point. Titmuss was, furthermore, at various points social policy advisor to the Labour party, in and out of office, and sat on a number of official committees and enquiries. He also authored two Fabian Tracts, The Irresponsible Society (discussed below) and, in 1967, Choice and the Welfare State (Tract 370). Other members of Titmuss’s department, notably Brian Abel-Smith, also contributed to the series, making it an important platform for spreading the ideas and approach of Titmuss and his followers to the wider labour movement and beyond.

Titmuss’s Fabian Society lecture was delivered only a few weeks after the 1959 general election, easily won by the Conservatives and famous for the (much misquoted) Tory slogan, ‘You’ve Never Had it So Good’. Speaking at Titmuss’s memorial service in 1973, Richard Crossman, the former Labour cabinet minister and himself a contributor to the Fabian Tracts series, said of Titmuss’s address that it was ‘One of the finest… I heard him give’. After editing, the lecture was published in 1960 as Fabian Tract 323, The Irresponsible Society, and became one of Titmuss’s most famous, and influential, works. Its content and afterlife tell us much about Titmuss’s view of social welfare and the state of contemporary British society. Much of it also resonates today.

For such a short piece The Irresponsible Society is a remarkably complex document, but at heart it is concerned with morality and the aims of social policy. It should be seen, too, as a cry of rage and frustration about contemporary Britain, especially in the light of the recent election result. So, for example, the notion that all social problems had been solved by the coming of the ‘welfare state’ was a ‘myth’ which was being used to justify cuts to public services (Titmuss always put the expression ‘welfare state’ in inverted commas, signifying his view that post-war reconstruction was an as yet incomplete project). Political and economic power, meanwhile, continued to lie in the ‘hands of those educated at Eton and other public schools’, with bankers and business leaders being among the leading culprits when it came to suggesting cuts in welfare expenditure. The undoubted material progress of ‘the affluent society’ was, nonetheless, morally corrosive and in any event unevenly distributed, as rising inequality showed. So what was required was moral leadership to address problems at home and abroad, such as racial intolerance and global inequalities. Titmuss firmly believed that the second world war had engendered social solidarity, social cohesion, and, consequently, social reconstruction, and frequently referred to the impact of the Dunkirk evacuation and the Blitz. He therefore expressed astonishment at recent Conservative statements which equated Labour party members with communists and fascists, statements which would have been ‘unthinkable in the context of 1940 or 1945’. Taking the contemporary picture as a whole, and particularly the pursuit of affluence rather than the tackling of inequality, contemporary Britain thus bore ‘simply the mark of an irresponsible society’.

For such a short piece The Irresponsible Society is a remarkably complex document, but at heart it is concerned with morality and the aims of social policy. It should be seen, too, as a cry of rage and frustration about contemporary Britain, especially in the light of the recent election result. So, for example, the notion that all social problems had been solved by the coming of the ‘welfare state’ was a ‘myth’ which was being used to justify cuts to public services (Titmuss always put the expression ‘welfare state’ in inverted commas, signifying his view that post-war reconstruction was an as yet incomplete project). Political and economic power, meanwhile, continued to lie in the ‘hands of those educated at Eton and other public schools’, with bankers and business leaders being among the leading culprits when it came to suggesting cuts in welfare expenditure. The undoubted material progress of ‘the affluent society’ was, nonetheless, morally corrosive and in any event unevenly distributed, as rising inequality showed. So what was required was moral leadership to address problems at home and abroad, such as racial intolerance and global inequalities. Titmuss firmly believed that the second world war had engendered social solidarity, social cohesion, and, consequently, social reconstruction, and frequently referred to the impact of the Dunkirk evacuation and the Blitz. He therefore expressed astonishment at recent Conservative statements which equated Labour party members with communists and fascists, statements which would have been ‘unthinkable in the context of 1940 or 1945’. Taking the contemporary picture as a whole, and particularly the pursuit of affluence rather than the tackling of inequality, contemporary Britain thus bore ‘simply the mark of an irresponsible society’.

The pamphlet’s publication was treated as an important occasion by the Labour party, with its public launch being chaired by its leader, Hugh Gaitskell. Reporting this event, the Guardian noted Titmuss’s contribution to ‘social thinking on the Left’ while suggesting too that his ‘austere view of society, and the stark egalitarianism implied in his analysis, may not be accepted by everyone, even in the Labour party’. This was an allusion to debates within the Labour party over how to respond to ‘the affluent society’, with ‘revisionists’ such as Anthony Crosland (and, for that matter, Gaitskell) suggesting that its potential should be embraced. Titmuss himself took his lecture on the road, using it as the basis for a number of talks in different locations and to different audiences over the coming years. He used such occasions to expand on his original ideas. So, for instance, in a lecture to the Workers’ Educational Association in 1962 he took the opportunity to single out the treatment of the ‘coloured population’ and recent discriminatory legislation. Whatever the Labour opposition’s shortcomings, Titmuss remarked, ‘it is to the credit of the Labour party and its leader that it wholeheartedly opposed this measure’. This was a reference to the 1962 Commonwealth Immigrants Act which sought to restrict the inflow of potential migrants and was in part a response to growing racial tensions as manifested by the 1958 Notting Hill riots.

We can now begin to piece together some of the key elements of what came to be called the ‘Titmuss paradigm’, which for the liberal left was to be the dominant way of seeing social welfare for the rest of the 1960s and, in some respects, beyond. Inequalities had to be tackled – in health, in socio-economic circumstances, and in race (gender was, arguably, a bit more problematic for Titmuss). A non-judgemental approach should be taken to those in receipt of state-financed social services while the ‘welfare professionals’ who provided such services had to be carefully monitored. Professional self-interest, in other words, must not be allowed precedence over the needs of service users (Titmuss had bodies like the British Medical Association in mind here). Such aims needed to be addressed by social policies underpinned by a moral vision whereby individual and collective altruism would be enabled and greater social solidarity and social cohesion achieved. Although not without its faults, for Titmuss the institution which most closely embodied such an approach was the National Health Service which was, initially at least, universal (all citizens could access it), comprehensive (all services were provided), and free (no direct financial exchange took place between patients and carers). Titmuss was particularly impressed by the British system of blood donation wherein individuals voluntarily gave blood, in their own time and for no reward, and without knowing who the recipients would be – altruism in its purest form displaying, in the famous phrase, ‘the kindness of strangers’. This was the way, then, to replace an ‘irresponsible’ society with one that was ‘responsible’, not least in its placing of collective needs over those of individuals.

Admirable as Titmuss’s approach was – he was sometimes called a ‘secular saint’ – it was not unproblematic. Even some of his supporters began to question whether, for example, people would always, even when given the opportunity, act altruistically. This was not, it was suggested, a true reflection of human psychology. More ominously still, by the early 1970s the ideas of bodies such as the Institute of Economic Affairs (IEA) were beginning to gain purchase. The IEA and Titmuss were old sparring partners, with the former arguing, for instance, that the free market and economic growth were better, and more efficient, providers of welfare than the state. Titmuss’s final book, The Gift Relationship, compared blood donation in Britain with that in the United States, where both supply and demand tended to be commercially driven. It was also, though, the culmination of a long-standing, often acrimonious, debate with the IEA over the role of markets in health care on both sides of the Atlantic.

Where does all this leave Titmuss in the early twenty-first century? His first Fabian Tract, The Irresponsible Society, remains essential reading for anyone interested in the history and aims of social policy (it can be read online via LSE’s freely-available digital library). If nothing else, his somewhat intemperate rants against Old Etonians and vested interests raise the spirits in troubled times such as our own. There can be little doubt, too, of his genuine commitment, here and elsewhere, to the disadvantaged. Whether, though, the ‘Titmuss paradigm’ is a useful, practical, guide to present-day welfare policy is a rather different matter.