The miserabilist tendency

Mark Perryman finds a new history of the Labour left overlooks the art of the possible.

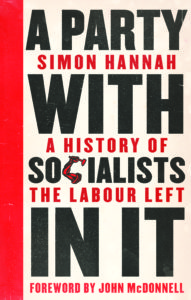

Simon Hannah’s history of the Labour left is unashamedly partisan. Nothing wrong with that, and as the latest book from the admirable 21st century reincarnation of The Left Book Club, most readers will guess that is its intention before turning too many pages.

But this also creates a problem. The account Hannah provides of Labour’s foundation is relatively uncontroversial and few are going to be motivated enough to have a row over just how good a socialist the party’s patron saint, Keir Hardie, may or may not have been. And as for Ramsay MacDonald, such is the contempt for that sorry period in the party’s history that MacDonald’s name is pretty much only ever used as a historically correct insult in Labour circles.

Yet, even all these yesterdays produce interpretations shaped by the politics of the historian. Stafford Cripps is for some a hero, for others a traitor. What, however, is most interesting about Cripps is his immersion outside the confines of Labourism in the popular front of the 1930s, most particularly against fascism. This was one of those rare examples of a break with Labour’s inherent tradition of what Neal Lawson has rather waggishly labelled ‘monopoly socialism’. It was made all the more special because it reached its high point at Cable Street and in the International Brigades of the Spanish civil war. Along with the hunger marches of the National Unemployed Workers Movement, these moments in history stand in stark contrast to the go-it-alone mentality that frames not just Labour’s right but too often its left too. On this subject, Hannah does not have enough to say.

The reputation of a second key figure of Hannah’s history – Aneurin Bevan – was framed by a similar, if different, challenge to ‘monopoly socialism’. His role in creating the NHS, unarguably Britain’s most cherished public institution, is told very well. However, the original vision behind it belonged to a Liberal, Beveridge. When Bevan brilliantly described what the spirit of ’45 was about to become: “We have been the dreamers. We have been the sufferers. And now we are the builders,” he was speaking as a Labour man of course, but his ‘we’ wasn’t just Labour, crucially it was the people. Bevan’s politics were no less radical for their popularity, the enduring support for the NHS is testament to this. But that ability to reach beyond the party’s activist base remains all too rare. Hence most of the episodes Hannah recounts in the history of Labour’s left are moments of defeat and reversal. Party chauvinism, what some now call tribalism, is a fatal flaw almost all sections of the party suffer from. It needs to be recognised as our collective responsibility.

Bevan rose once more as the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament grew in the late 1950s, yet, as Hannah re-counts eventually he was to betray the cause of unilateralism. What was more interesting is how he, and other figures of Labour’s 1950s left, related to this emergent mass movement.

CND, like almost every mass movement led by the left, has been staffed, organised and led by groups and figures outside of Labour. For the most part these campaigns recognised Labour as a crucial ally but the effort and imagination to generate them came from the non-Labour left. There’s quite possibly a sociological explanation for this: as new members are discovering, Labour membership is time-consuming with an endless round of meetings, motions, elections, party-run campaigns and the like. While the inclination might be towards the extra-parliamentary, is there the time to fit it all in?

More than any single individual it was Tony Benn who sought to break this activist logjam. In the 1980s Bennism framed a politics of resistance in and against Westminster. Until Corbyn, British politics had never seen the like of this. And like Corbyn, Benn spoke over the heads of his party to reach, engage and inspire a wider public. But unlike Benn – and it is admittedly harsh to say this – Jeremy is a winner, not a loser. He stood for the leadership and won, and when he was challenged to run again he did so and won for a second time. When a snap general election was called, every professional political commentator, without exception, predicted Labour would be wiped out. Corbyn didn’t do enough to win but he did so much better than expected, justifying a belief that he could win next time.

And this is the point that Hannah’s occasional miserabilism misses. His pervasive certainty that almost anybody we put faith in will disappoint obscures the ‘art and craft’ of the possible. Corbyn has created a moment of possibility. He’s done it from the left, and his keenest supporters came from there too, mostly disorganised, many more movementist than Labourist. But most important of all there is a much broader swathe of Labour opinion who simply want to be on a broadly progressive winning side. Victory, more than anything else will determine Corbyn’s legacy. And so that, for now, is all that matters.