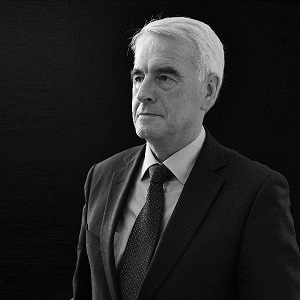

The unlikely shadow chancellor

John McDonnell’s elevation to shadow chancellor startled him as much as anyone. He talks to Mary Riddell about his unexpected journey from crusader of the left to leading the battle to regain Labour’s economic credibility.

John McDonnell’s elevation to shadow chancellor startled him as much as anyone. He talks to Mary Riddell about his unexpected journey from crusader of the left to leading the battle to regain Labour’s economic credibility.

John McDonnell appears blessed with unshakeable self-esteem or the hide of a rhinoceros. Either way, he is unoffended by the description borrowed from Thomas Hobbes and bestowed on the shadow chancellor by an anonymous critic. Is he really “nasty, brutish and short?”

“I didn’t recognize myself in that description. The reality is that for all my 18 years in parliament, I’ve been swimming against the stream. As a result, I had never been appointed to a senior position or, until recently, been allowed on a single committee. But I’ve always tried to maintain a relationship with other people.”

The tide turned for McDonnell on the day that Jeremy Corbyn, his friend and long-time fellow-traveller of the left, was elected leader of the Labour party. In the face of protest and dismay among many Labour MPs, McDonnell was named shadow chancellor shortly afterwards. Though he has now been ensconced for many weeks in the office once occupied by his predecessor, Ed Balls, the lack of any personal belongings lends a provisional air to his residency.

Such, at least, is the hope of those critics still appalled that the task of restoring Labour’s economic credibility sits on shoulders so hitherto unburdened by high office. Those who predicted instant meltdown were confounded by the measured conference speech and reasonable manner that gave McDonnell a better start than many had expected.

He ascribes that initial fluency to long backbench practice. “For years, I was preparing alternative budgets and intervening in debates. I was the first MP to raise [concerns over] Northern Rock. I was the first one to raise the banking issue. It’s a whole different world than the despatch box in terms of how you treat the House, but the detail is [similar]. I’m a hard-nosed bureaucrat, and I have been all my life.”

Neither a flinty character nor meticulous attention to detail has been enough, however, to spare McDonnell from opprobrium. In particular, he was mocked for promising that Labour would sign up to George Osborne’s fiscal charter, stipulating a budget surplus in 2019/20 and each year thereafter, only to recant a short time later on his promise.

“It was farcical piece of legislation, but I told Jeremy I was worried we didn’t have the votes to oppose it [and should] vote for the thing on the grounds it was completely irrelevant.” With Labour’s enthusiasm for anti-austerity mounting, the leader demanded a volte-face. “I said OK. I’m going to get shredded for this, but I’ll front it up, and we’ll go for it.”

And so he repented to the House, not only declaring his initial decision “embarrassing” but repeating the admission five times. “I did. Chris Bryant [the shadow leader of the House] said it was a wrong to say ‘embarrassing’ so much and [that I should remember] that the frontbench microphone picks up every word. But I wanted to be honest with people as well. A bit of humility amongst politicians does the soul good.”

While some of McDonnell’s colleagues might doubt his grasp on matters of the soul, most would acknowledge that the unravelling of Osborne’s planned tax credit cuts presented his opposite number with an early coup. And so McDonnell had a presumed advantage when, in his first major challenge, he rose to respond to the chancellor’s autumn statement.

Even so, he was nervous. “It’s a tough gig because all the cards are in their hands.” In the event, George Osborne held a fuller deck than anyone suspected. The double U-turn in which he announced that he would ditch his planned cuts to tax credits and the police demolished Labour’s two best lines of attack.

McDonnell had known that the tax credit changes would be softened, but he had no inkling of what Osborne was about to say. “We had got no wind of that,” he says. With his ammunition gone, McDonnell could only hail “two victories for Labour” and warn that many of the chancellor’s promises would prove hollow.

Far from settling for such a standard formula, McDonnell instead seized on the novel ploy of quoting from Chairman Mao and presenting a copy of his little red book to a chancellor who could scarcely believe his luck. Meanwhile McDonnell’s own colleagues appeared appalled that their left wing shadow chancellor should invoke the nostrums of one of history’s great butchers.

When we speak shortly afterwards, McDonnell sounds unrepentant, if faintly sheepish. Did he perhaps have a copy of the thoughts of Mao Zedong on his bedside table? “I found it under a pile of my student books when I was clearing out my study. I knew I was going to get an awful lot of stick about it from the media and the PLP, but I wanted to [highlight] asset sales to foreign governments. I’ve been ribbing them [the government] about selling stuff off to the Chinese, and this was one way of doing it. I wanted to get a headline about the asset sales.”

Does he have any regrets that his gesture backfired? “No, no. It was done in a spirit of irony and self-deprecation because I’m on the left. The most important thing was to get the story out there, and I’ve done that.” Had he told anyone on his own side of what he planned to do, or alerted Corbyn to the stunt? “No, not at all. Everyone was surprised.”

That furore over, the unlikely shadow chancellor now faces a greater battle than ever to regain credibility and outsmart his chief opponent. McDonnell’s background could scarcely be more different than Osborne’s. The son of a bus driver and a union official, he left school at 17 and took a series of unskilled jobs before going to night school and sitting his A-levels. Five years later, he got a place to study politics at Brunel University and subsequently obtained a master’s degree in politics and sociology from Birkbeck.

First a union official and then a deputy to Ken Livingstone on the Greater London Council, McDonnell never lacked diligence or ambition. Indeed, the only trait he shared with Osborne was their mutual desire to lead their party. McDonnell ran twice for the leadership, once against Gordon Brown in 2007 and then against Ed Miliband in 2010, failing to make the ballot on both occasions.

His elevation to the job of shadow chancellor startled him as much as anyone. “Seven months ago, I was working on the basis that I would slip quietly into the role of elder statesman of the left and prepare the foundations for the new left. I always thought the left would come back into power.” Having expected a breakthrough by 2020, McDonnell instead found himself catapulted into the front line.

At 64, and after suffering a heart attack two years ago, did he wonder whether he had the mental and physical stamina for the task? “Standing as leader twice wasn’t a stunt. It was because I thought I could take it on. I’ve always been serious about going into government and worked on the basis that you have to be ready if it happens the next day. I’ve always told the left that you can’t just make speeches. You have to come to terms with power and administration, and that’s what I’ve done.”

Whether he can dispel the ghosts of the past is another matter. Not long ago, his office denied that he had signed, or even seen, a demand by a left wing campaign group that MI5 should be disbanded and the police disarmed. The subsequent emergence of a smiling McDonnell holding the offending document appeared damning.

“What a cock-up,” he says. “I’d signed an anti-austerity statement. When they asked for a statement, I held up what I thought was [that one]. It wasn’t. It was another policy programme.” That mix-up followed closely on from the furore surrounding Corbyn’s reluctance to endorse a shoot-to-kill policy against terrorists on operations in the UK.

“The Metropolitan police [responsibility] is to use proportionate force, and of course we also have the reserve of lethal force. That’s all Jeremy was reiterating. But the minute you put shoot-to-kill on the agenda, it becomes an emotional thing.” While many MPs considered Corbyn’s initial response unforgiveable, McDonnell is merely critical of his team’s media strategy.

“We failed to rebut an insinuation after Jeremy’s interview. That’s where we fell down. Our rebuttal exercise has got to be quicker, and we’ve got to be sharper. We should have [acted] straight away. That’s lack of experience, in a way, and naivety. We’ve only been here for a few weeks, but we have to learn lessons pretty quick. Or otherwise people are going to lose confidence in us.”

Some centrists already proclaim a dearth of confidence, despite McDonnell’s promise that he backs Osborne on extra security spending and that a Corbyn government would keep the people safer than the Tories after refusing from the outset to consider police cuts. “My brother was a copper for 35 years. He was a commander, a trained hostage negotiator and responsible for the Queen and the royal family in Norfolk. So I know the issues around [police] resources.”

Crucial as economic issues remain, the Corbyn leadership seemed more destabilised by the Paris bombings and their aftermath. We speak shortly before the PM is about to make his pitch for Britain to join the war in Syria, following the UN security council resolution allowing for “all necessary means.”

“I am still of the view that the involvement of the western powers in the Middle East is a disaster, a long-term disaster. As soon as you have the involvement of the UK and the US, it exacerbates the problem. That’s my position, full stop. I certainly don’t approve of bombing raids. What I’m worried about is that you will get mission creep and troops on the ground. Then you get sucked into a [situation] that is extremely perilous in the long term. I’m not willing to support a military invasion in Syria or the Middle East any further.”

Throughout Labour’s internal disputes on whether to back bombing raids and whether the vote called by Cameron should be free or whipped, McDonnell’s position remained clear. “My inclination is that issues such as sending people to their potential death should be a matter of conscience. I think we have to do what we always have and give people the opportunity to exercise their consciences.”

And so, in the days before the Commons votes on Syria, McDonnell found himself at variance with Corbyn, who argued for a whipped vote until he was forced to retreat at the final shadow cabinet meeting before the war vote.

The internal rows and divisions exposed by the Syrian showdown is far from the only crisis to threaten Labour. McDonnell cannot however be accused of failing to offer olive branches to doubters. He is, for example full of praise for Chuka Umunna, who offered only thinly-veiled criticism of Corbyn, and lyrical in his admiration for the moderate front-bencher, Vernon Coaker. “I love Vernon. He’s not my politics, but he’s a really decent, honest, salt-of-the-earth bloke.”

Despite such overtures, Labour remains riven by dislike of some of Corbyn’s left wing staff appointments and by fear of being deselected. That anxiety, McDonnell says, is misplaced. “We’re not just a big tent – we’re trying to increase it.”

Such collegiate ambitions, I suggest, are hardly helped by interventions such as the suggestion by Ken Livingstone, that the moderate Kevan Jones, who has suffered mental health problems, should see a doctor after criticising Livingstone. “Anything like that is indefensible. We’re all learning a lot around mental health issues. It was really upsetting what Ken said. We’ve got to try and learn from it and move on.”

None of the unease within his party has diminished the gusto of the shadow chancellor. Long before the autumn statement was delivered, and despite its apparent success, McDonnell has considered Osborne as out of step with the people. “The attack on him and Cameron was posh boys. I always thought that unseemly and wrong. You don’t choose the class you are born into. But if you’re from a relatively wealthy background, you need to take special care. If you have never struggled to pay the rent or mortgage, you need to empathise with those that might.”

Whether McDonnell is a byword for empathy is another matter. Though affable and mild-mannered in private, he is by his own admission an unclubbable figure who was barely known to many Labour MPs before the Corbyn accession. A Who’s Who entry saying that he was “fermenting the overthrow of capitalism” and an assertion that he would like to “assassinate Margaret Thatcher” (a poor joke, he says) stand as future epitaphs to a political career.

But for now at least, John McDonnell is destined to fight the corner of a parliamentary party which mostly does not warm to him, and never may, against the most politically agile chancellor of modern times. McDonnell must trust that his “iPad socialism”, marrying technological advance with traditional protection for workers, takes shape under the guidance of advisers, such as the Nobel Laureate, Joseph Stiglitz. McDonnell’s new buzzword, “futurity”, might amuse those centrists who consider him to have the forward-looking instincts of a stegosaur, but the shadow chancellor is well-used to shrugging off criticism.

Does he still aspire to lead his party? “No, not now. I’m in my sixties. I want to get Labour elected in 2020. I’d like to serve a term as chancellor so that we get the economy back on the road. At that stage, I think the new generation we’re bringing on would consolidate Labour in power for a generation.” Would that also be Corbyn’s plan? “Jeremy’s never discussed the longevity of his administration with me. But his view has always been: let’s win the election in 2020 and see where we go from there.”

While such an ambition might strike critics as far-fetched or even risible, McDonnell has never shirked a battle, be it against the Tories or the sceptics of his own benches. In the words of Chairman Mao: “No matter how harsh the environment, even if there is only one person left, he will keep on fighting.” It remains to be seen whether the crusader of the left can prevail against the forces ranked against him.

Mary Riddell is a columnist for the Daily Telegraph

Image credit: Andy Hall for The Observer